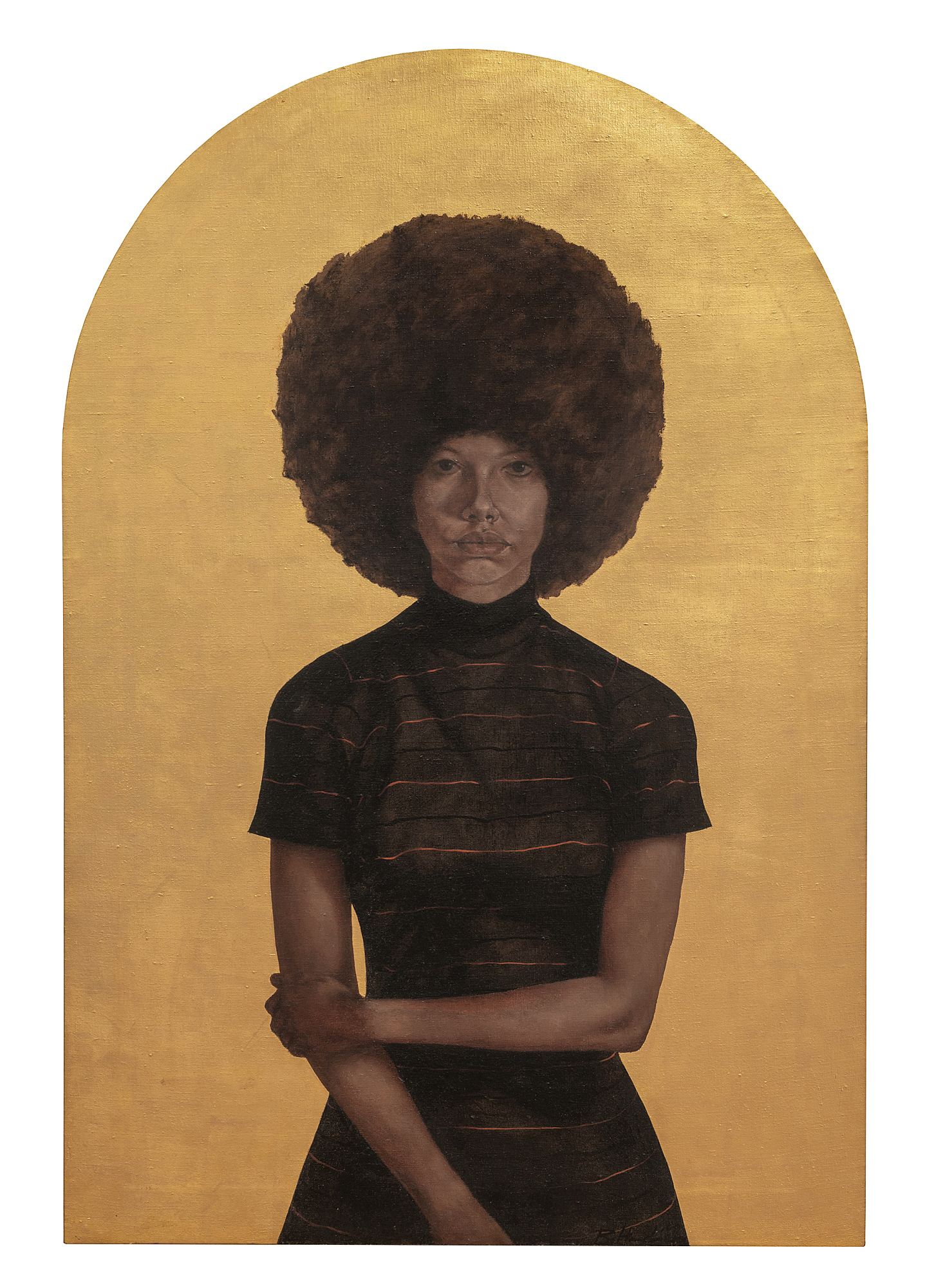

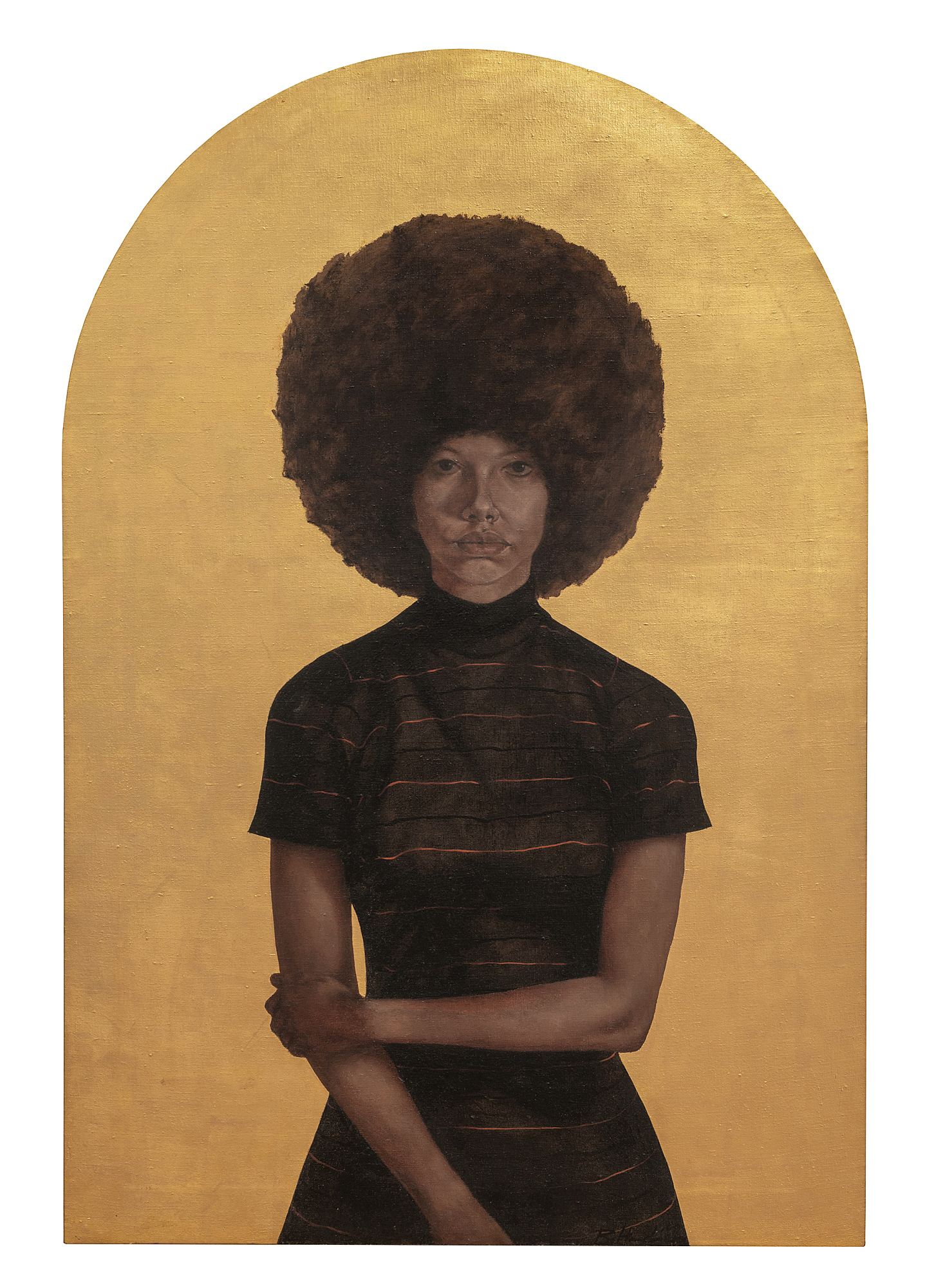

“Lawdy Mana” by Barkley L. Hendricks, 1969, oil and gold leaf on canvas, 53 ¾ by 36 ¼ inches. The Studio Museum in Harlem, N.Y.; gift of Stuart Liebman, in memory of Joseph B. Liebman. Artwork: © Barkley L. Hendricks; courtesy of the Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York City.

By James D. Balestrieri

NEW YORK CITY — I wanted to start this essay in some erudite way, but the truth is really very simple. The first Barkley Hendricks painting I ever saw was “Lawdy Mama.” The portrait was part of an exhibition of diverse artworks by a variety of American luminaries, from early portraits to quilts and installation pieces. Some of them were really quite good. “Lawdy Mama,” however, blew my mind, as we used to say in the 70s when I was very young and trying very hard — and failing even harder — to be cool. I see the word “very” three times in those first four sentences — which is unusual as I try to find adjectives and adverbs other than “very” when I write, especially when I write about art. But the experience of “Barkley L. Hendricks — Portraits at the Frick” isn’t an occasion for breaking out the thesaurus. The immediacy in the works demands an immediate response. If the response is “very,” so be it. And while “very” gets a bad break because of its hackneyed overuse, it’s worth remembering that the word has its roots in Latin, in veritas, meaning, simply, “truth.”

Painted in 1969, “the year [Black Panther] Fred Hampton was assassinated,” as Frick curator Dr Aimee Ng reminded me in an interview, “Lawdy Mama,” like most — or all — of Hendricks’s portraits isn’t overtly political. “It shows rather than tells,” Ng goes on, “almost in the way that Seventeenth Century Dutch still life paintings of prized, imported objects show us the pathways and structures of colonialism.” Indeed, the absence of identifiable activism in Hendricks’ work left him open to criticism from both the Black and white art establishment — “outside of his time,” as Ng says. And yet, as the works in the exhibition demonstrate time and again, Hendricks’s portraits embody — I use this word in its literal sense — a politics that transcends the Black Power era and specific issues of injustice.

The subject of “Lawdy Mama” insists on maintaining a measure of distance, projecting what might almost be termed an aristocratic hauteur, an attitude the exhibition links to the Frick’s Van Dyck portraits hanging in galleries not far from Hendricks’s work. Hendricks knew the Van Dycks and Van Eycks at the Frick — he often said it was one of his favorite museums — as well as the great portraits in museums in New York, Philadelphia and throughout Europe, finding greater inspiration in them than in the prevailing currents of modernism and more politically charged works. Van Dyck’s noble British sitters convey control — self-control — and what “Lawdy Mama” expresses, above all, is a woman in control of her body and environs. Consulting curator Antwaun Sargent says, “Barkley was having his own conversation about the Black body, against the grain of political and socio-political thought.” After four centuries of white ownership and absolute authority, “He was painting the experience of the body,” insisting on showing the people he painted “in control of their bodies.” For Barkley Hendricks, Black Power, expressed pictorially, is simply the power to be, to be in the world, to inhabit space as one wishes, and to be seen as one wishes. A look at any one of the Van Dycks impresses a single idea, “Attitude is armor,” and it’s precisely this idea that Hendricks’s portraits appropriate, make modern, make timeless. Further, in Hendricks’s work, attitude — the assertion and insistence on individuality as expressed through the body — is activism.

“Self-portrait with Black Hat” by Barkley L. Hendricks, 1980-2013, digital C-print. 27 ¾ by 18 ¾ inches. Jack Shainman Gallery, New York City. Photo © Barkley L. Hendricks; courtesy of the Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York City.

But the more I look at “Lawdy Mama,” I see that the title both is and isn’t the subject of the painting (in fact it was inspired by a Nina Simone song). Yes, she could be “Lawdy Mama,” but those words, or something like them, might also be what I might say — to myself, not out loud — if I were confronting this woman (I would probably just try to exhale). That left arm crossed over, holding the right, is a closed gate. I am holding my breath (having failed to exhale), squared up against a judgmental simmer that reveals very little. Wrath, however, isn’t out of the question.

Then there is the matter of the gilt background and the lunette curve at the top of the canvas, stretched by Hendricks himself. Here Hendricks plays a deep cut in the album of the art of the West, transporting me back to the mosaics of St Mark’s in Venice and Monreale in Palermo, to Byzantine, Medieval and Russian religious icons and iconography, and to Gustav Klimt’s gilt-haloed Austrian women. Suddenly, “Lawdy Mama” is elevated and sanctified; Sunday morning bells ring in the distance. Despite the artist’s self-deprecating statement that the gilding is just a “shiny thing,” ritual comes into play in this “trialogue” — this trial, a test of sorts — between subject, artist and witness. Sargent describes the moment in this way: Hendricks “boldly and subtly makes the Black body the subject of a work of art… it’s an assertion of self in a history, an art history, a politic, that might not see you.” If the words “Lawdy Mama” might be construed as an invocation to a goddess whose gaze penetrates your soul, the judgment in “Lawdy Mama” is also the painting’s judgment of the viewer — “How do you deal with me?” — where “me” is, yes, the woman in the painting but also the painting itself, asking, insisting, “Where do I fit into your art historical scheme? What if I don’t fit and don’t want to? What then? Reconcile with that.” It’s a trial that isn’t over, not by any means.

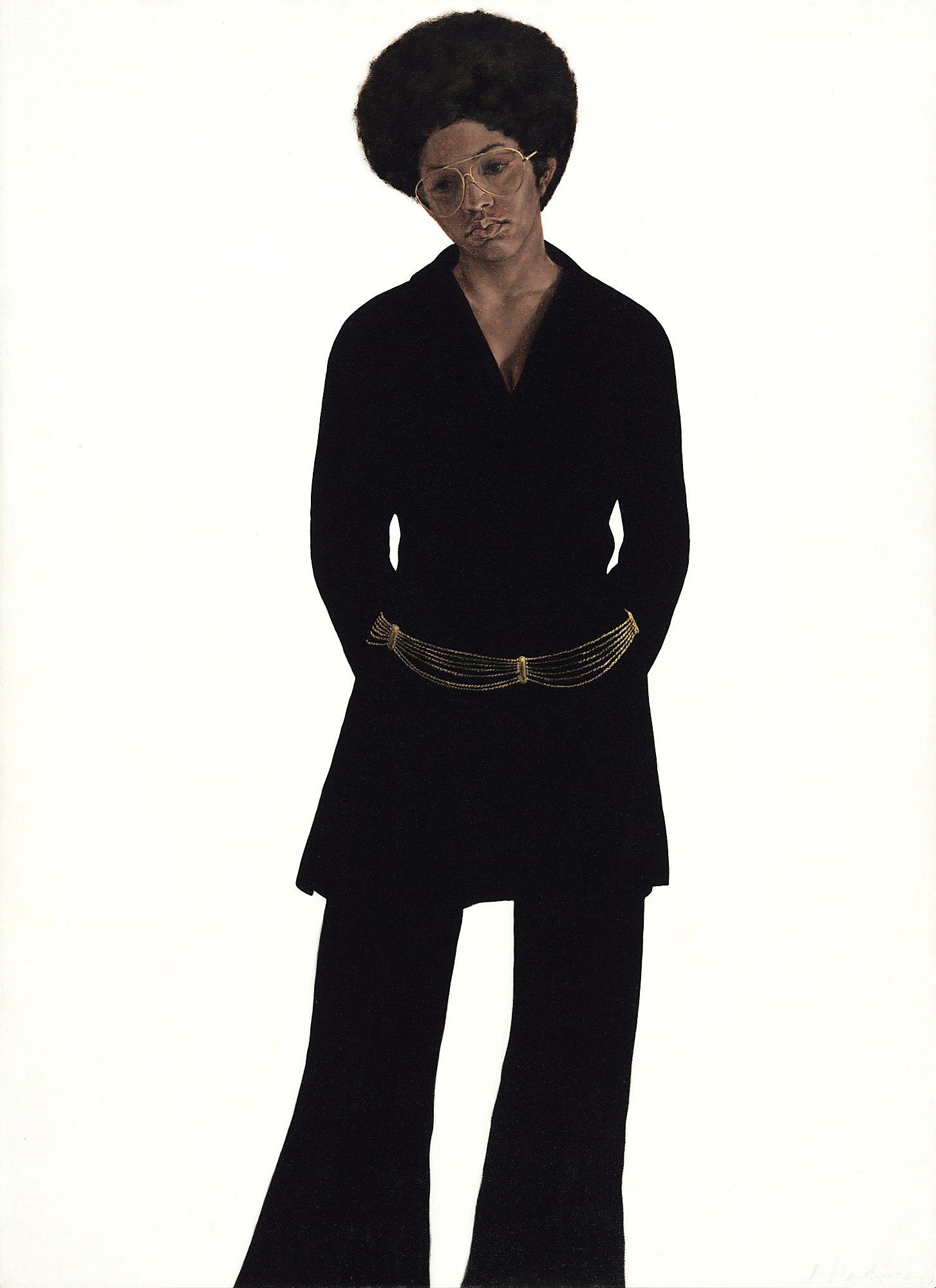

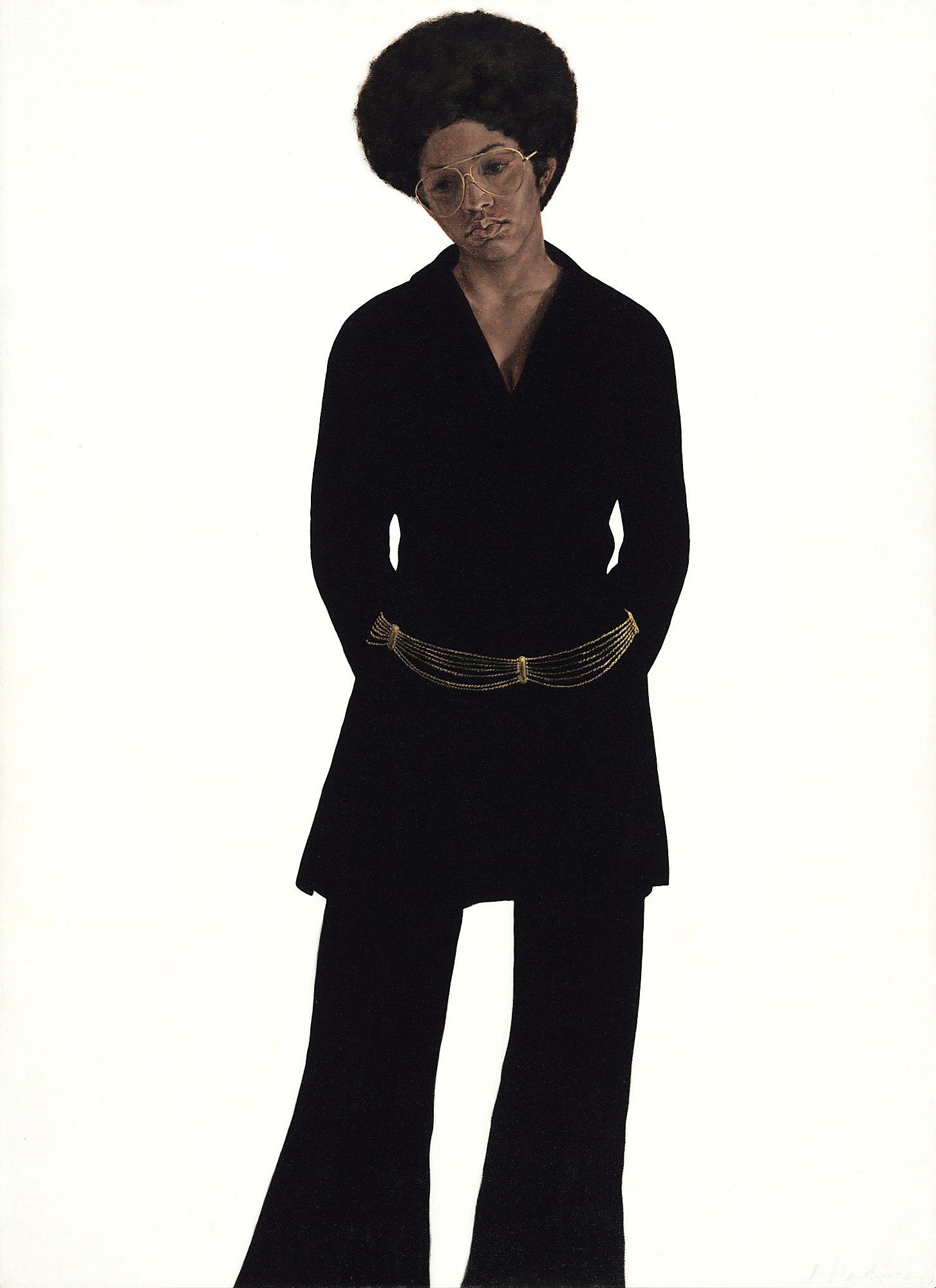

“Miss T” by Barkley L. Hendricks, 1969, oil and acrylic on canvas, 66-1/8 by 48-1/8 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art; purchased with the Philadelphia Foundation Fund, 1970. Artwork: © Barkley L. Hendricks; courtesy of the Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York City.

It’s hard not to see Hendricks as a modernist in light of the numerous contemporary figurative painters who rejected absolute abstraction and who are still squarely in the modernist pantheon: Lucien Freud, Francis Bacon, Fairfield Porter, Alice Neel, Fritz Scholder and many others. Should we reconsider them as counter-counter-cultural? Or were there — are there — different expectations placed on Black artists? Do we demand images of suffering, expressions of anger, statements of issues? Do we look for the slogan first? Do we project it where we don’t immediately see it? Do we impose it where it isn’t? The jury — time, history, art history — is still out, still deliberating. Indeed, in response to rejections he received on account of his work being too realistic, Hendricks refused to be “pinned down,” as Sargent says, defending his portraits as abstractions, as artistic compositions that were really about line and color, insisting that the art establishment pay attention to his “classical training, formalism and experimentation” and thereby “rejecting his rejection and asserting control over his personhood” — and his artistic identity.

Briefly, because I do not want to stray too far from the art, Barkley Hendricks was born in Philadelphia in 1945. He attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, eventually graduated from Yale, and was professor of Studio Art at Connecticut College from 1972 until 2010. Trips to Europe and North Africa in the 1960s left him enthralled with the art and practice of the Old Masters and dismayed by the absence of Black subjects in the long history of Western art. In this light, Hendricks’ portraits emerge as moments of redress, partial restorations of balance that he generally began with the camera, which he called his “mechanical sketchbook,” often approaching interesting strangers on the street, the people who would people his art. The Frick exhibition displays a selection of Hendricks’ photographs alongside the portraits to which they ultimately led; the juxtaposition offers deep insight into his practice.

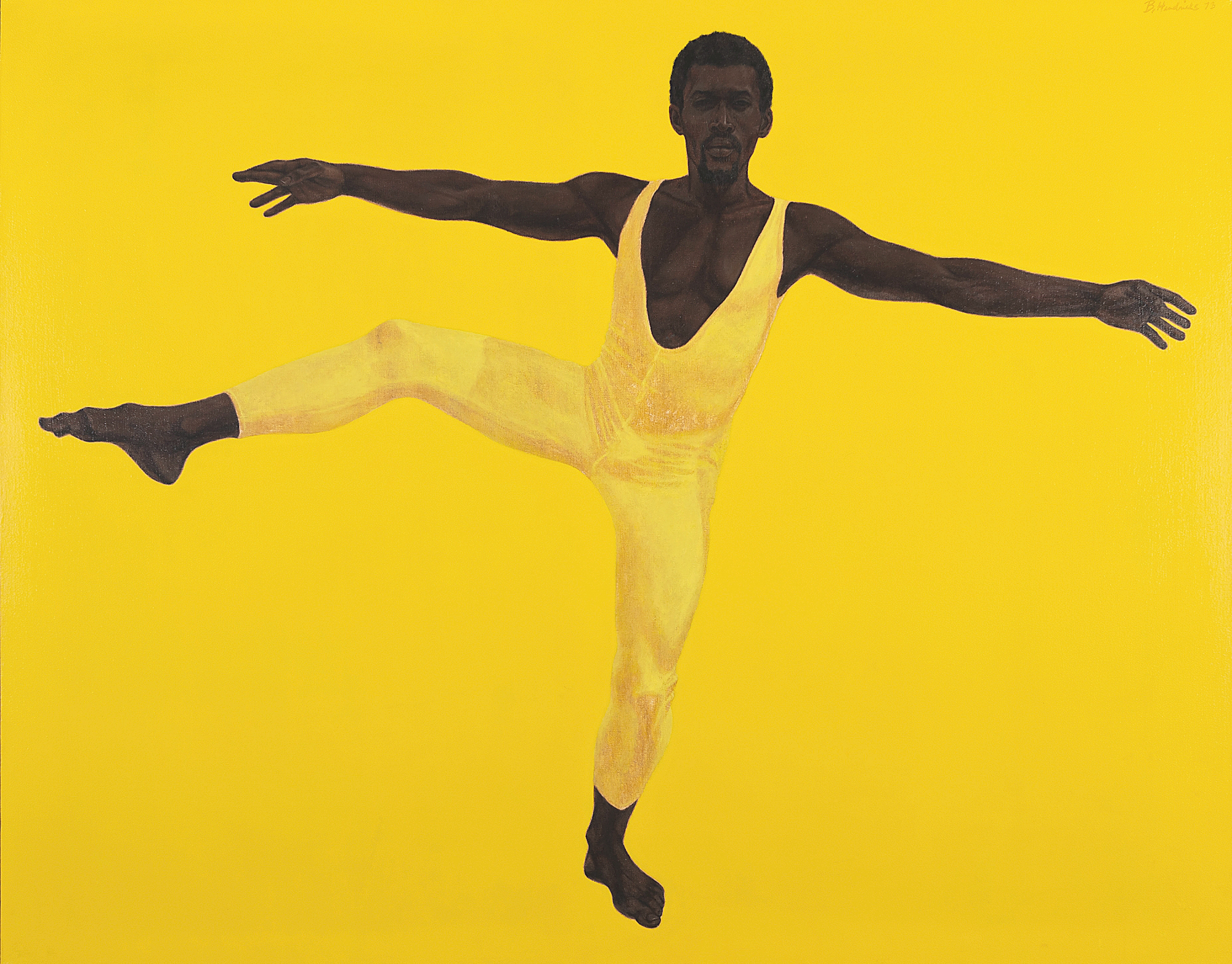

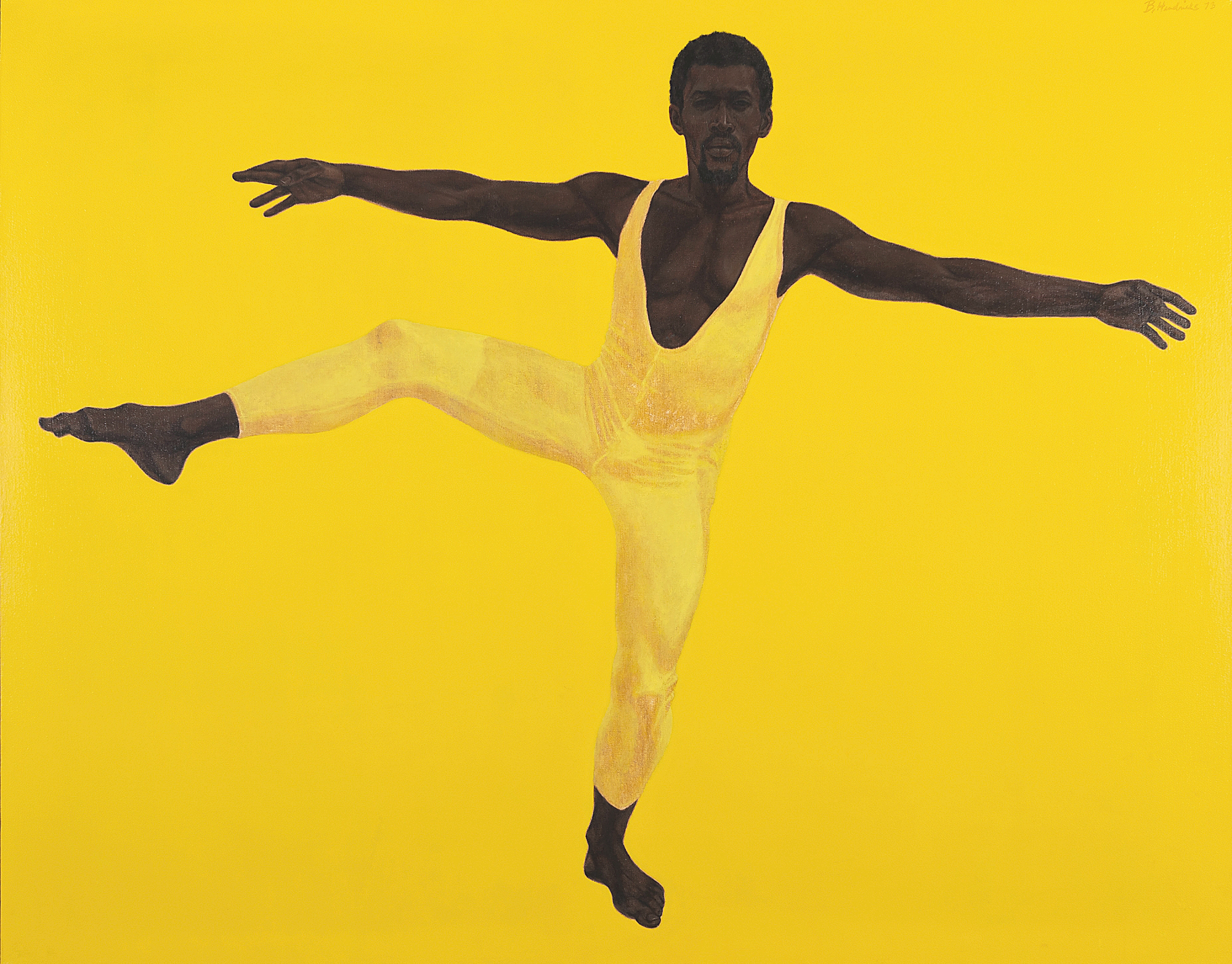

Hendricks’ photographs are very much situated in time, featuring his sitters — standers, posers, dancers — surrounded by 1960s-70s cityscapes or elements in the artist’s studio. In the painted portraits, Hendricks “erases,” as Ng says, “setting and time,” locating the portrait in “an imaginary place.” In many works, Hendricks makes the color of the subject’s clothing the same as the color of the background, uniting figure and ground. However, as in “Steve,” “Woody” and “October’s Gone… Goodnight,” he painted the ground in acrylic, a flat pigment that provides subtle contrast to the outlined figure. Once again, I am subjected to an aesthetic vertigo, the flat grounds in single colors hearkening back to the pigment of Medieval and Renaissance manuscript illumination and flinging me forward to the tempera of Andrew Wyeth. “I can do anything the Old Masters did — and my contemporaries, too,” Hendricks’ works seem to say, “but I do it my way,” reinvigorating the Renaissance term emulation, an artistic surpassing of a model, in opposition to mere imitation. His way even included giving up portraits for two decades — just when it looked as though they might catch on — choosing instead to concentrate on landscapes. “He wasn’t chasing popularity,” Ng adds, but looking at the portraits now “you might think they were made now. They’re Instagrammable, stylish, cool.”

“Woody” by Barkley L. Hendricks, 1973, oil and acrylic on canvas, 66 by 84 inches. Baz Family Collection. Artwork: © Barkley L. Hendricks; courtesy of the Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York City.

For Hendricks, who passed away in 2017, success was elusive. He achieved a measure of fame but never made it big, though his star was on the ascendance near the end of his life; the art market and museum worlds were getting wise to his work. But Hendricks knew his story and his truth. Sargent interviewed the artist before his death and says, he “wasn’t grateful. He’d lived erasure and rejection. He wasn’t interested in rewriting history.” Perhaps it is ever thus with those who are seen as antique, or at least, insufficiently contemporary, while actually being visionaries, out ahead of their own time.

Hendricks’ influence on contemporary Black portrait painters and photographers like Kehinde Wiley, Amy Sherald, Mickalene Thomas and Awol Erizku is, however, unmistakable. These artists and others, such as Nick Cave, contribute essential essays to the catalog that accompanies the exhibition. Their revolutionary interest in figurative work, Ng says, is a “recentering of the body,” especially among American artists of color, and might well be a response to the pandemic and to the socio-economic schisms in the country, a way of reconnecting us to ourselves and to one another. “Figural art,” she says, “is a democratic way of approaching visual culture, immediately recognizable and accessible to any viewer. We know what a body is. We read body language all the time.”

Sargent applies this idea to Hendricks’ aims in his catalog essay, “Barkley L. Hendricks: To Be Real,” quoting the artist, “As Hendricks put it, ‘I wanted to deal with the beauty, grandeur, style of my folks. Not the misery. We were ahead in many areas of culture like fashion, certainly music.’ He would often see someone ‘bopping down the street’ and ask, ‘Can I do a shot?’ This democratic way of making portraits — creating an image as a kind of witness — cuts against the tendencies of the period” (p. 44).

“Sisters (Susan and Toni)” by Barkley L. Hendricks, 1977, oil and acrylic on linen canvas, 66 by 48 inches. Virginia Museum of Fine arts, Richmond, Va.; funds contributed by Mary and Donald Shockey, Jr. Artwork: © Barkley L. Hendricks; courtesy of the Estate of Barkley L. Hendricks and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York City. Photo © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Travis Fullerton photo.

As far as antecedents in African American art, I see hints towards Hendricks in the portraiture of Henry Wilmer Bannarn and Charles Henry Alson. I see something of Hendricks’ figural economy in Aaron Douglas. I also see an affinity between Hendricks and the facture of one of Douglas’s teachers, Winold Reiss, a white, German-born American painter whose celebrated pastel portraits of Harlem Renaissance luminaries such as W.E.B. DuBois are realistic renderings of Black faces and hands set against abstract or all-white backgrounds. I find no direct connection between Hendricks and Reiss — yet — but I think there might be food for thought in the comparison and, perhaps, someday, a fascinating dual exhibition.

In truth — in veritas — Barkley Hendricks was, is, and will always be very much his own artist. Very.

“Barkley L. Hendricks – Portraits at the Frick” is at Frick Madison, at 945 Madison Avenue, from September 21 to January 7. For information, 212-288-0700 or www.frick.org.