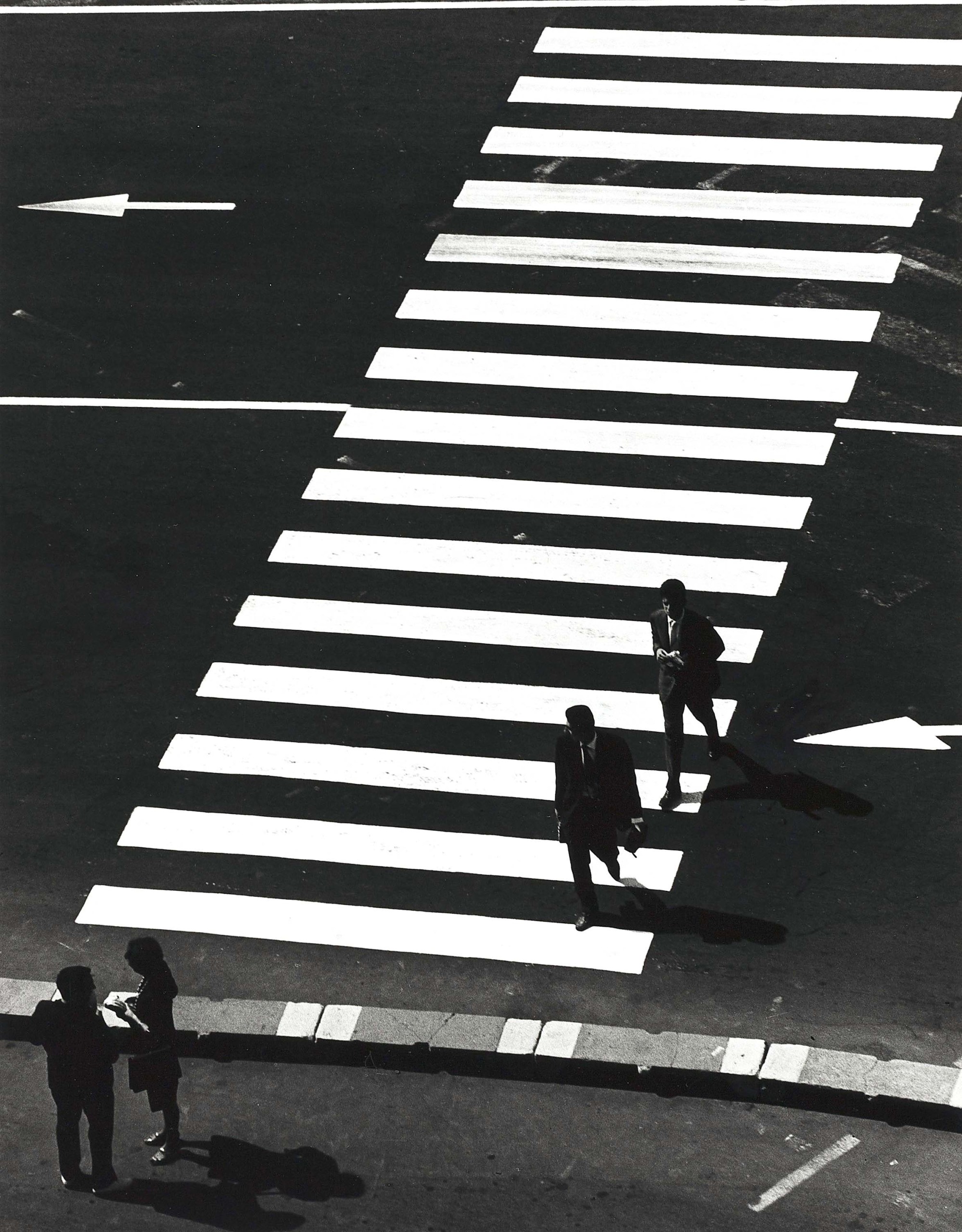

“Paris” by André Kertész (Kertész Andor) (American, born Hungary, 1894–1985), 1929, printed 1950s–60s, gelatin silver print, 16-5/8 by 20-5/8 inches. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 2014.173.

By Kristin Nord

RICHMOND, VA. — In “American, Born Hungary: Kertesz, Capa, and the Hungarian American Photographic Legacy,” we meet a succession of luminaries whose work was significant in shaping American sensibilities. This comprehensive exhibition is a labor of love for Alex Nyerges, the Virginia Museum of Fine Art’s (VMFA) director and CEO, where the exhibition will be on view until January 25. He has teamed up with Karoly Kincses, founding director of the Hungarian Museum of Photography in Budapest to showcase the work of 33 trailblazing Twentieth Century Hungarian photographers, through a total of 170 works and ephemera. Who better to oversee this project than Nyerges, a Rochester, N.Y., native and an international award-winning photographer, curator, author and photo historian.

Nyerges begins his tale in early Twentieth Century Budapest, when the city reigned as a thriving cultural capital. At the time, this beautiful city laid claim to vibrant art and decorative arts museums, opera and ballet companies, an active theatre scene and a world class orchestra. It was also home to a large, affluent Jewish population, as well as artists who were well-aware of the Parisian movements of Modernism and Surrealism.

But World War I dealt a devastating blow to Budapest. The war decimated the city’s male population and the city was laid low in short order by “astronomical” inflation, Nyerges writes, in the exhibition catalog. Mounting antisemitism fueled the enactment of a succession of laws that were designed to limit Jewish participation in virtually all aspects of everyday life.

“Near Cerro Muriano (Cordoba front)” by Robert Capa (Endre Erno Friedmann) (Hungarian, 1913–1954), circa September 5, 1936, gelatin silver print, 19 by 23 inches. Courtesy of the George Eastman Museum, Gift of Magnum Photos, Inc.

Nyerges quotes one Budapest academic, as if anticipating what was to come, reporting, “the distant future is dark. The air is unbelievably poisoned, it feels as if in a room filled with carbon dioxide, one must get out, otherwise it gets suffocating.”

From the summer of 1919 through the end of the following year, almost the entire corps of modern artists fled the capital, most electing to emigrate to Vienna, Berlin, or, shortly later, to the Weimar Bauhaus. Jewish Hungarians without the wherewithal were trapped in poverty. More than 430,000 overall would be deported to Auschwitz and other death camps when the Nazi-controlled regime began.

It was against this backdrop that many Hungarian refugees sought to rebuild their lives in new locales. But all of them faced a daunting language barrier, Nyerges explained in a recent interview, as Hungarian itself was “largely impenetrable” to the outside world. A career in photography would offer many a lifeline and a chance for refugees with minimal English skills to make a good living. For these transplants, Nyerges writes, “the camera became a universal translator — a transnational and multilingual tool; a common communicator.” Some would never learn to speak English fluently, but their photographs would speak for them.

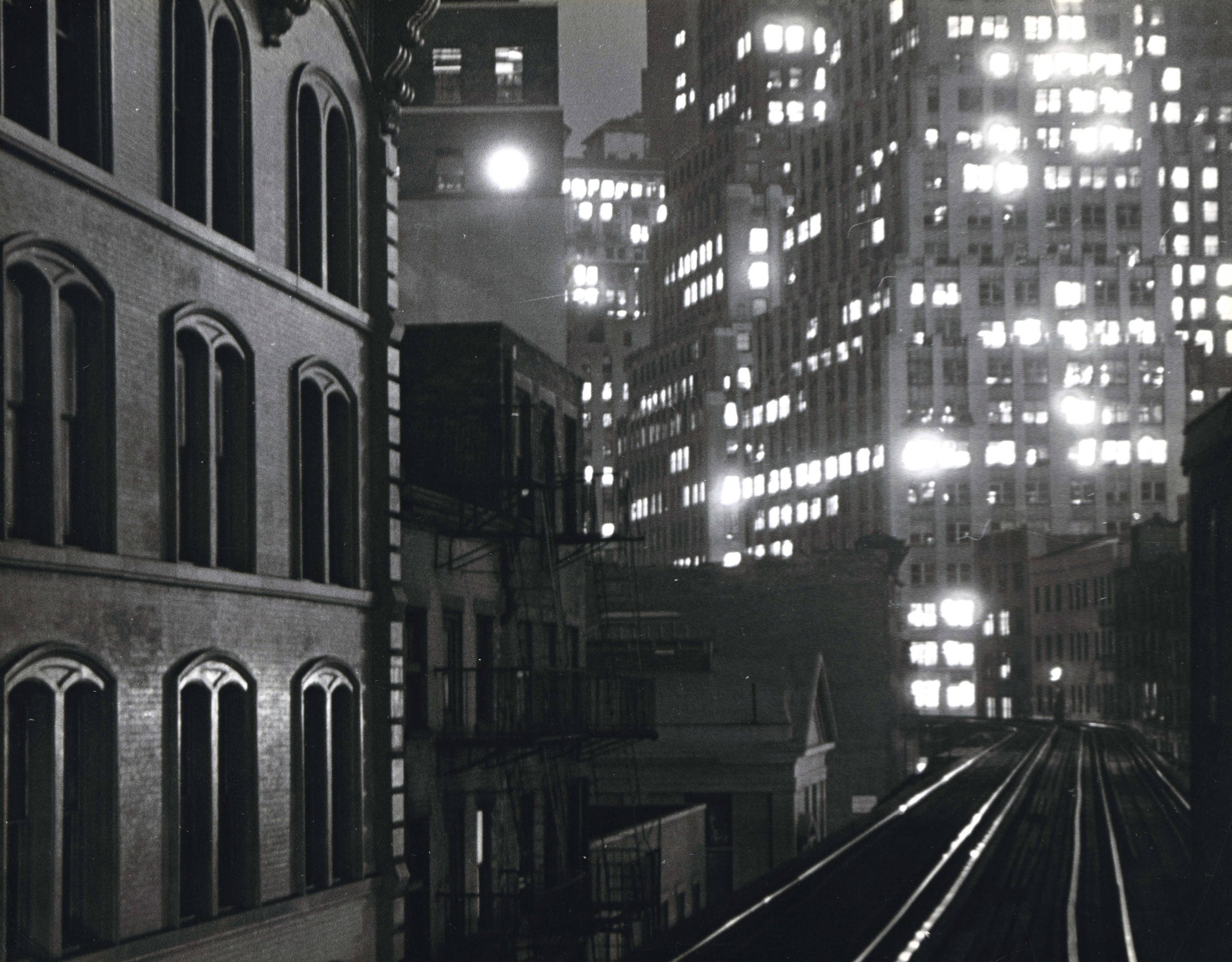

“Under the Third Avenue EL, North of 27th St., New York” by Arnold Eagle (American, born Hungary, 1909–1992), 1939, gelatin silver print, 9¾ by 12 inches. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of Alex Nyerges and Kathryn Gray, 2021.872 ©Estate of Arnold Eagle.

Nyerges points us to the observations of the photo historian Nissan Perez, who theorized that the camera for these men and women became “a portable tool of wanderers, much like a musical instrument,” as well as “a vehicle of activism and the means by which to establish a new identity.”

The prominence of so many Hungarians as photographers has remained an under told story, Nyerges says, because in their efforts to assimilate many of them changed their names: The Capa brothers — Cornell and Robert — were originally the Friedmann brothers, Endre Erno and Kornell; Mermelstein Marton, who became Martin Munkácsi; Mádl Miklós, who became Nicholas Murray; Weisz Paula, who became Paula Wright; and Alabok Janos, who became John Albok. There were many others.

If these Hungarian photographers shared the common denominator, Nyerges writes, “it was because they were born into the magical, culturally alive and intellectually special turn-of -the-century Hungary. Budapest was the nexus of it all.”

For this exhibition, which draws upon the museum’s large collection, Nyerges has taken care to focus on the stories and works of specific masters. Overall, he says, “When one looks at the collective work of many of these Hungarian American photographers, it becomes clear that their aesthetics and technical approaches were deeply rooted in the underpinnings of modern abstraction.” But the astonishing experimentation and innovation from this group attests not only to their gifts but to their ability to respond to need in the camera’s golden era.

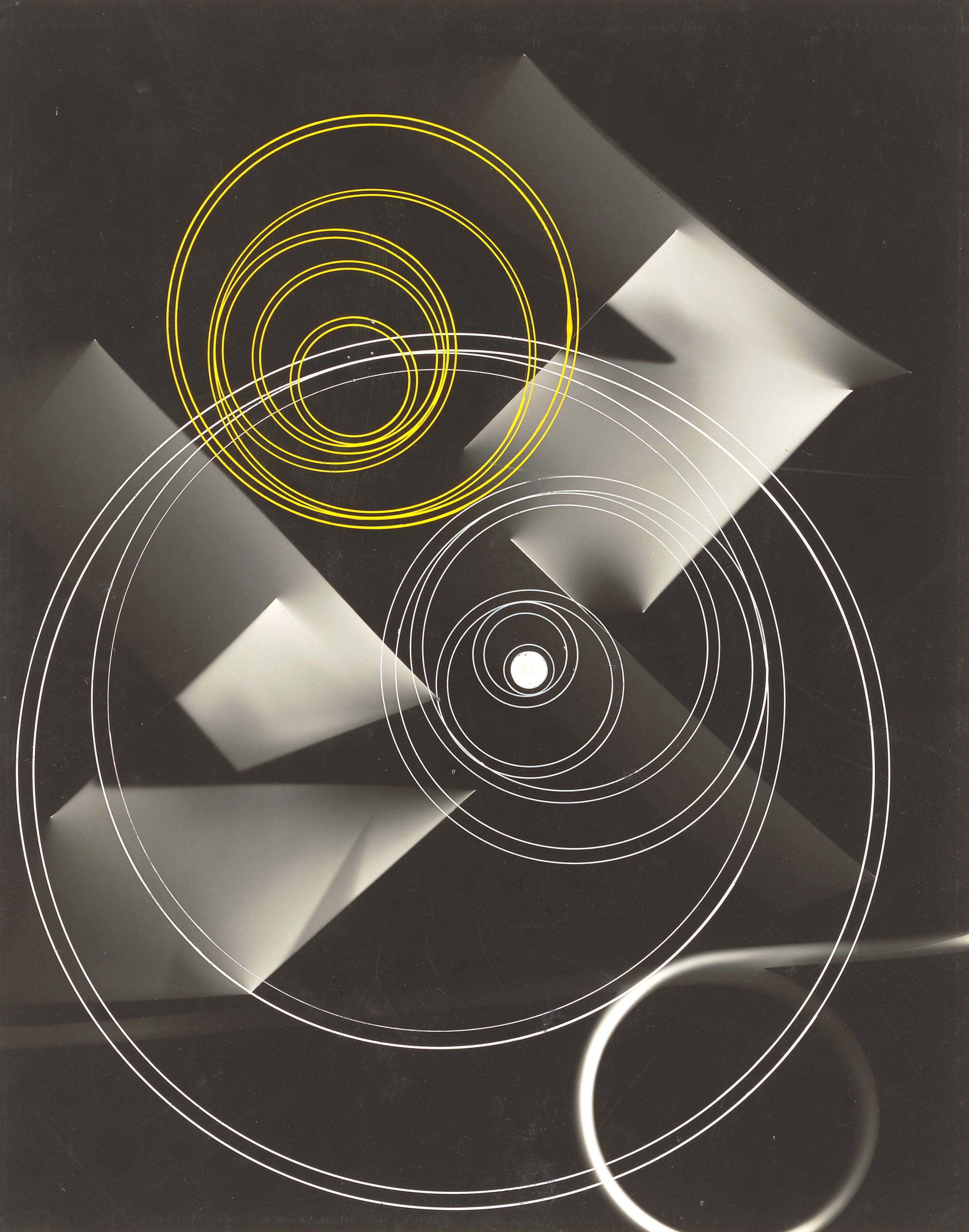

“Juliet with Peacock Feather and Red Leaf” by György Kepes (American, born Hungary, 1906–2001), 1937-38, gelatin silver print with gouache, 15 by 12 inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Pepita Milmore Memorial Fund, 2014.20.1.

André Kertész had moved to Paris in 1925 and his work in a solo exhibition was acclaimed by critics. “His best photographs are miracles of calm gravity;” Kertész’s biographer would write, “they reflect the purity of his soul.”

But Kertész’s brilliance was dimmed for decades when he toiled as a commercial photographer. When he relocated and began working in New York, American editors purportedly told him, “Your pictures talk too much.”

“I photographed real life,” he would respond later. “Not the way it was but the way I felt it. This is the most important thing — not analyzing, but feeling.”

Kertész is credited with having given birth to two principal branches of modern photography: candid photography with a small camera, and subjective reportage. Many felt that his long career with Condé Nast had thwarted his growth as an artist, but he would break free of those constraints later in life and his artistic career would move into high gear. Free to work as he wished, he won the gold medal at the Venice Biennale, had a lauded exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art and published several acclaimed books.

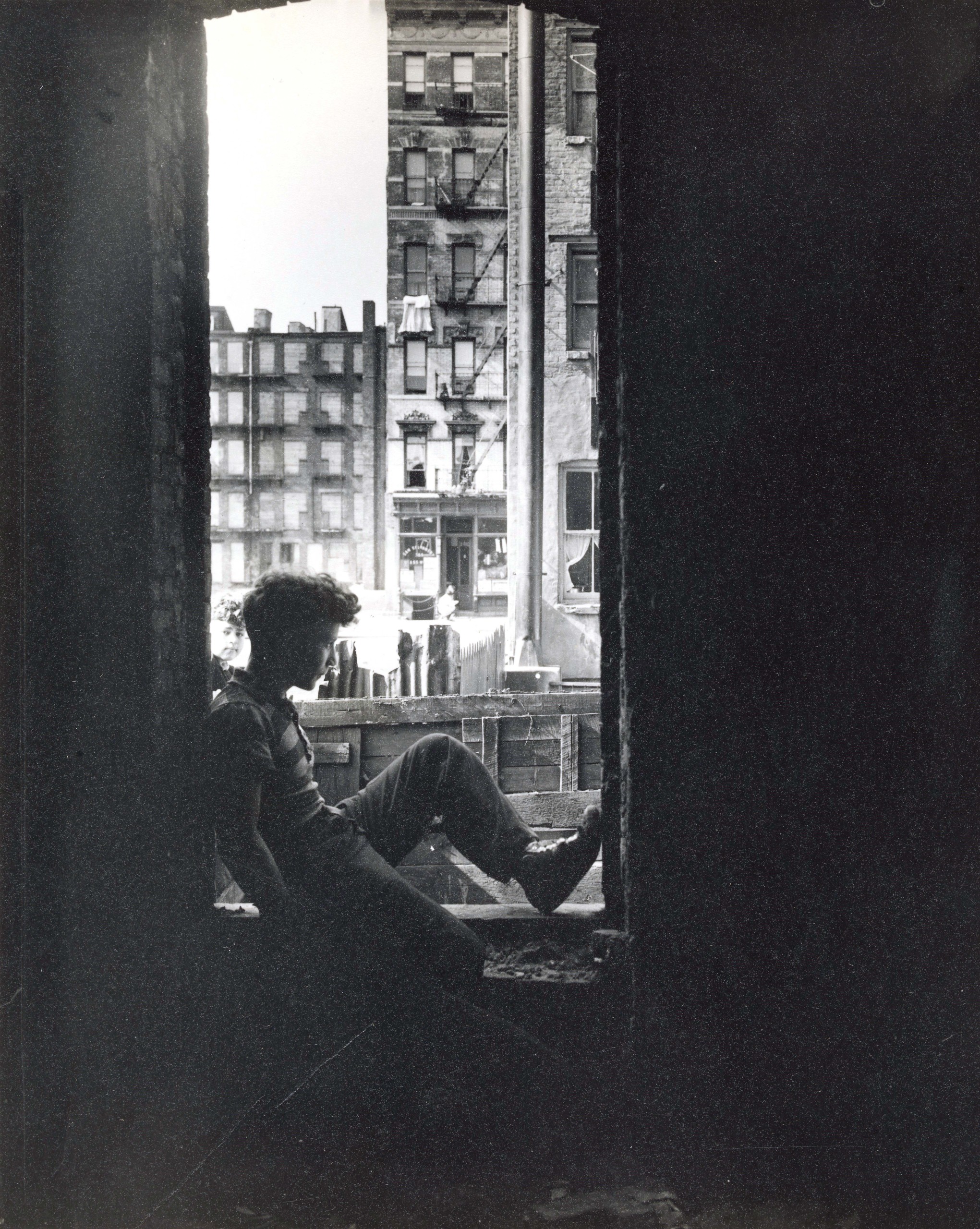

“Stairway” by Max Thorek (Torok Maximilian) (American, born Hungary, 1880–1960), circa 1939, gelatin silver print, 22 by 18 inches. Black Dog Collection.

László Moholy-Nagy was a polymath, who worked first with Walter Gropius at the Bauhaus, and led the short-lived New Bauhaus after he relocated to Chicago. Of the work of Kertész and Maholy-Nagy, the curator notes, “Their work could not have been more different, Moholy-Nagy with his experimental edge and Kertész more traditional. But they shared a pair of common bonds; they were firmly connected as modernists and they were both Hungarians living in a foreign land.”

“One can’t speak of modernism in photography without evoking the names of Russian Aleksander Rodchenko, the American May Ray, and the Hungarian American, László Moholy-Nagy,” the curator adds. “This new era was characterized by techniques like photomontage, the photogram and the purposely disorienting vantage point. Maholy-Nagy, always an innovator, created all three of these elements in modern photography.”

“The era of the 1920s and 1930s occupied what might be called the intellectual history of photography,” Nyerges continues. “Although it was a century old, photography was repeatedly described during this time as having only recently been truly discovered.”

Over time, György Kepes would become known for his photograms, Munkácsi, for his transformative sports and fashion photography; André de Dienes and a number of other Hungarians for their portraits of Hollywood starlets; Balthazar Korab for his architectural photography.

“Photogram (yellow and white circles)” by György Kepes (American, born Hungary 1906–2001), 1939, gelatin silver print with gouache, 25¼ by 21¼ inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Corcoran Collection (Museum purchase with funds from the Women’s Committee of the Corcoran Gallery of Art), 2015.19.5092.

Marion Palfi, who became a respected social activist, chronicled the plight of the underprivileged and became known as an urban Dorothea Lange. Other Hungarian women photographers of note included Anna Barna; Jolán Gross-Bettelheim and Suzanne Szasz, whose images were tapped by Edward Steichen for his landmark 1955 exhibition, “Family of Man.”

Robert Capa’s grainy scenes of American soldiers landing on Omaha Beach remained burned into the collective memory of generations, and his body of work readily earned him reputation as perhaps the greatest photojournalist of his generation. After the war, Capa joined forces with Cartier-Bresson, Chim and George Rodger to found Magnum, the artist-managed and owned cooperative that grew to be one of the most important and influential photo agencies in the world.

“Capa was their leader, with the ability to wrangle the disparate talents of countless egos, tempers and disciplines into a cohesive and unparalleled group of photographers on the world stage.” Nyerges writes.

There are extraordinary images in this exhibition that run the gamut, from Capa’s war photojournalism to Kertész’s “Underwater Swimmer” to Maholy-Nagy’s sharply angled courtyard square, from Nikolas Muray’s “Sandwich and Mayo” to Munkácsi’s evocations of exuberance and joy. There are scenes of gritty street life (“Fire Escape, NY; Lexington Ave. at 44th St.” and the famous “Under the Third Ave. El”) and scenes of wonder (whether in Central Park in winter, or a scene captured at the World’s Fair).

“Central Park, New York, Winter Reflections” by Paula Wright (Weisz Paula) (American, born Hungary, 1930–2015), circa 1960, gelatin silver print, 20-5/8 by 16-5/8 inches. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Kathleen Boone Samuels Memorial Fund, 2020.133.

Other photographers and filmmakers would make their mark in Los Angeles. Two would establish major film companies: Fried Vilmos who took the name William Fox and created Fox Film Corporation and Adolph Zukor, who founded Paramount Film Studios.

“We are living in the golden age of photography,” Munkacsi at one point proclaimed happily. “It is a modern expression and also a natural means of expression. And because it is spontaneous, there is more chance of immortality for the novice in this art than in any other today.”

The French photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Nyerges notes, returns us to the work of Kertész, for the ways in which “he sought out the simple, the obvious, and the understated, capturing it on film and then transforming it into a statement about life, humanity, and our existence.”

“One can see why Cartier-Bresson was so inspired,” the curator writes. “Kertész was struck by the moment, that fleeting second when a camera records a memorable image or misses it.” And it was that gift to see and capture that telling moment “that has inspired generations of young artists to change the world through photography.”

“American, Born Hungary: Kertesz, Capa and the Hungarian American Photographic Legacy” will be on view through January 25, at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. It will then travel to the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, N.Y., where it will be on view from September 26 to March 1, 2026.

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts is at 200 North Arthur Ashe Boulevard. For information, 804-340-1400 or www.vmfa.museum.