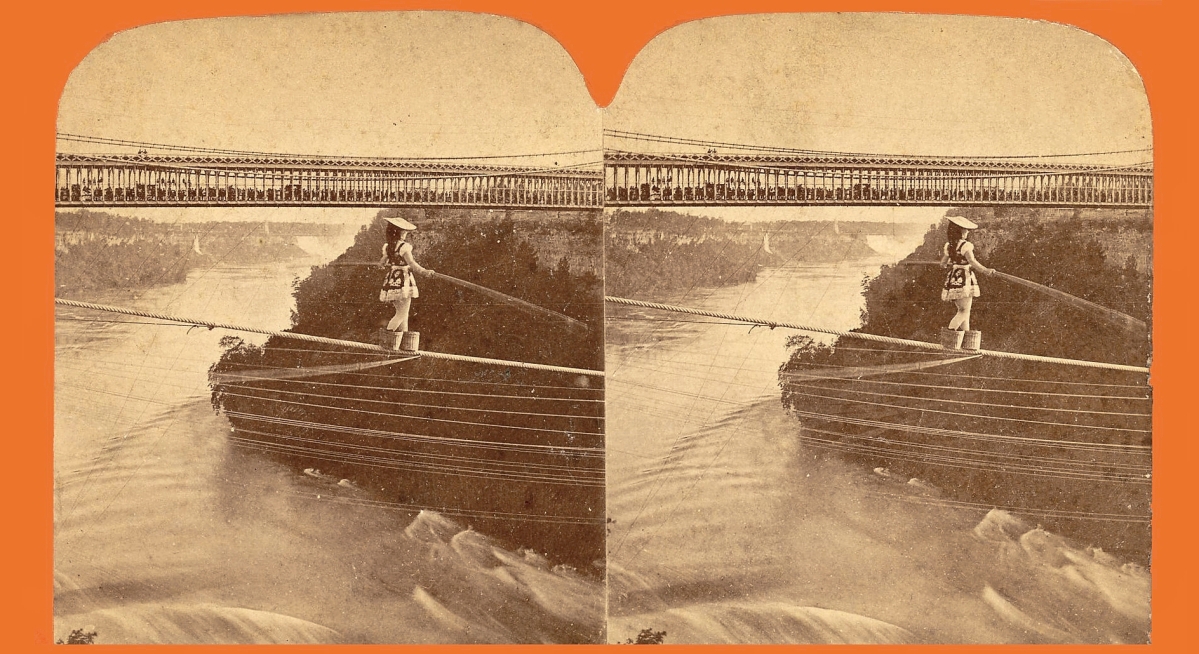

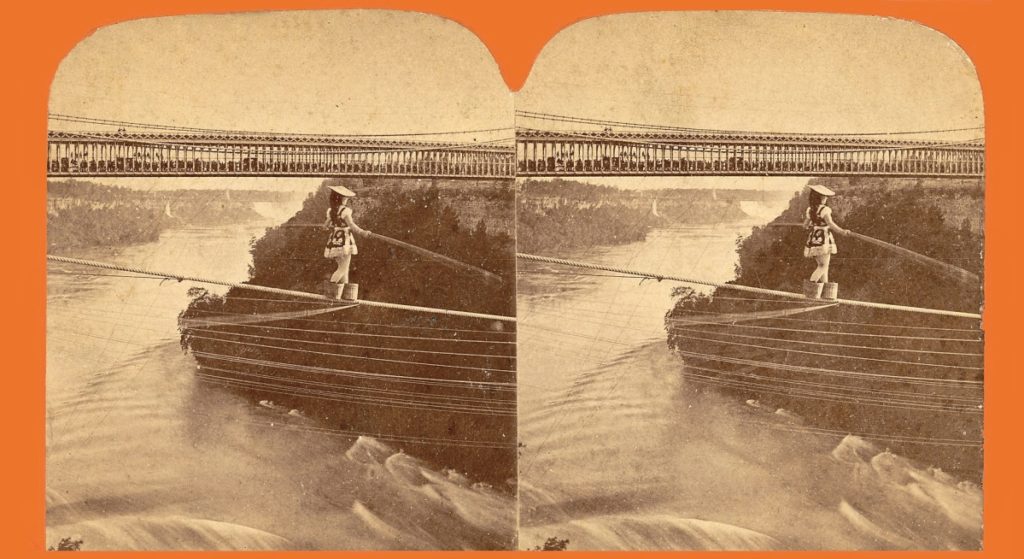

“Niagara Falls – Only Woman to Tightrope Over Falls” by Charles Bierstadt, 1876, stereograph with albumen photographs. Private collection.

By James D. Balestrieri

YONKERS, N.Y. – Three brothers sought three dimensions.

In painting, Albert Bierstadt (1830-1893) sought to transcend perspective, to make the elements in his paintings pop off their supports; through stereography, Albert’s brothers, Charles (1819-1903) and Edward (1824-1906), made photographic images appear to float.

“The Bierstadt Brothers: Painting and Photography,” on view at the Hudson River Museum through September 10, isn’t a large, sweeping exhibition but it asks some large, sweeping questions about visual culture in the Nineteenth Century – and in the Twenty-First. Ours is an image-driven culture; our species privileges the eye above the other sensory organs. “Seeing is believing” and “Show me” and “Show, don’t tell,” are mantras of human society. And yet, with the rise of deep fakes and – just now – broadly available A.I., we know that we are more susceptible than ever to surfaces that appear real. Indeed, with A.I., the nature of reality and the question of authorship find themselves on shaky ground, ground that philosophy and ethics are laboring to catch up with. The truth is, there are blizzards of images out there, all of them aimed, via one algorithm or another, at us, “us” collectively and “us” as individuals. It’s exhausting, yes, but it’s also indicative of a hunger that can’t ever be satiated. We say we’re tired of our devices, but FOMO (fear of missing out) is a real thing. We don’t want to be left out and we certainly don’t want to miss out on the new, the now, the wow. They – whoever “they” are – have found our weak spot, and they’re flooding through.

We think this is new, but if it is, it is only new in scale, in the sheer number of images that bombard us.

The Bierstadt Brothers – Albert, one of the great American painters of any century – and his brothers, Charles and Edward, pioneers of stereography – wanted American eyes (any eyes, really) on the images they created.

“Dawn at Donner Lake, California” by Albert Bierstadt, circa 1871-73, oil on paper mounted on canvas. Collection of the Joslyn Art Museum. Gift of Mrs C.N. Dietz, 1934.

Albert, Charles and Edward Bierstadt were born in Solingen, Germany. When they were quite young, they emigrated with their family to New Bedford, Mass., then, perhaps, the whaling capital of the world at a time when whale oil lit lamps across the globe. New Bedford was a bustling boom town, and its inhabitants, from the wealthy to the working class, sought diversions. Albert showed promise as an artist and found ready patrons who paid for him to study in Düsseldorf, which was one of the centers of high romanticism. Albert readily imbibed the lofty ideals of the movement that had given rise to artists such as Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840). On his return to the United States, Albert saw that the grandeur of the American landscape, especially in the West, might prove an outstanding field for his endeavors. At the same time, having seen the new medium of photography, he encouraged Charles and Edward to take up the camera and join him as he roamed America’s wilderness.

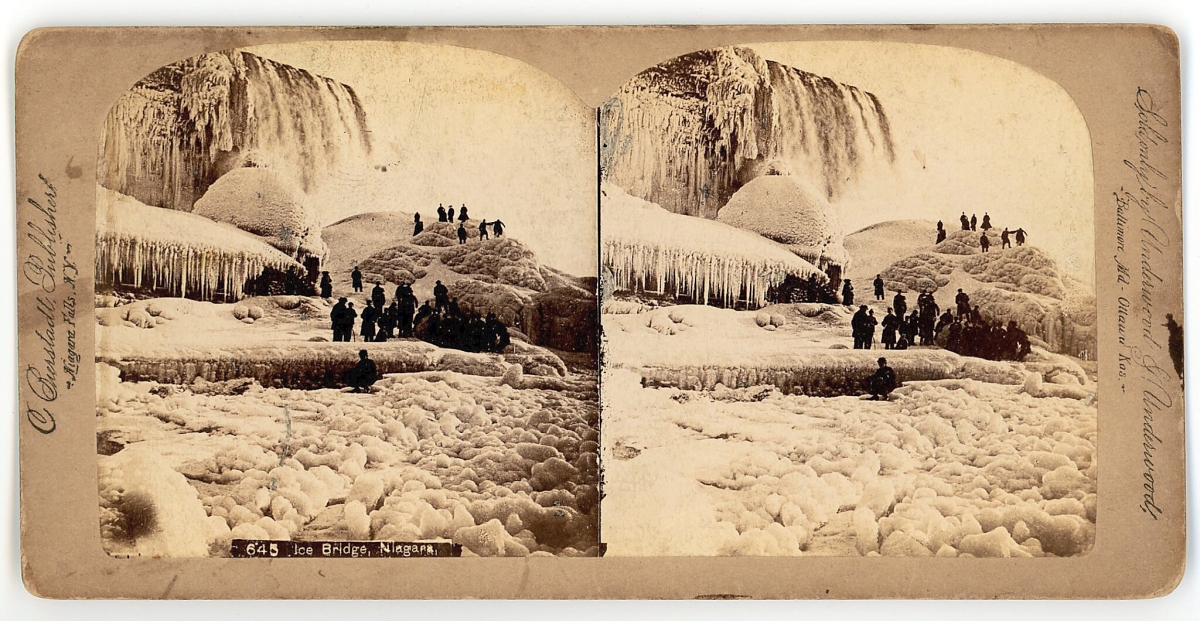

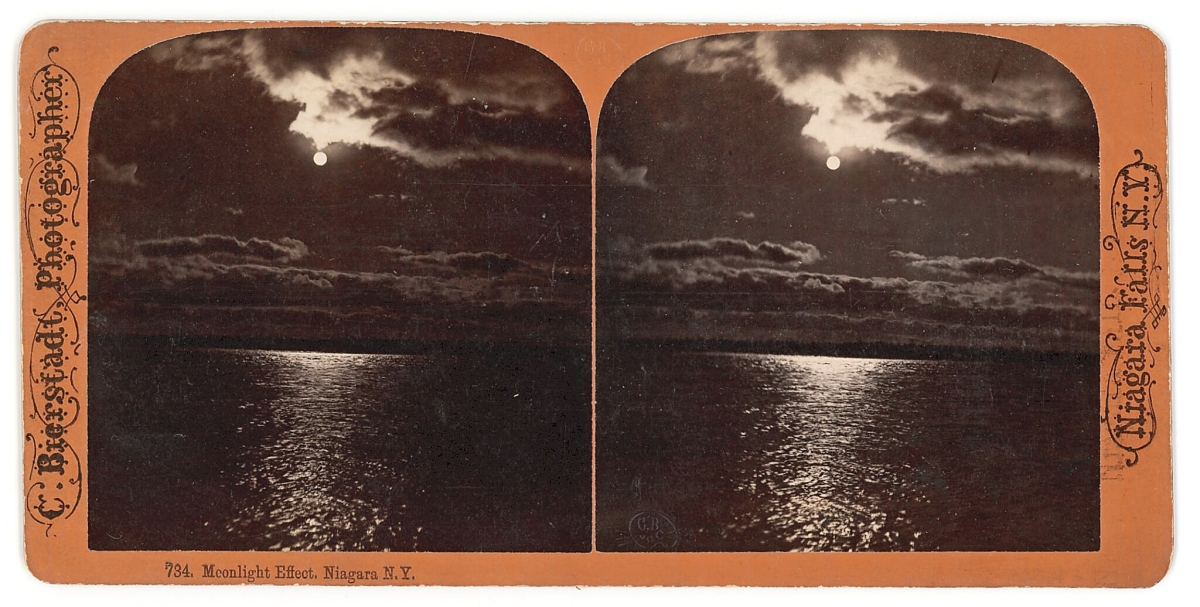

The stereoscopic camera and viewer are ingenious. The camera places two lenses side-by-side, replicating human binocular vision. The two images produced are not-quite-identical, but almost. When seen through a binocular, prismatic viewer, the two images merge, creating the illusion of dimensionality. As part of the exhibition, you can sit at a table and look through a viewer at reproductions of some of Charles and Edward’s stereographs. The effect is as uncanny in 2023 as it must have been in the 1850s. To give just one example, Maria Spelterini, the woman in Charles Bierstadt’s 1876 image, “Niagara Falls – Only Woman to Tightrope Over Falls” seems suspended – with her feet in peach baskets(!) to add to the difficulty – as if walking on air instead of on a tightrope.

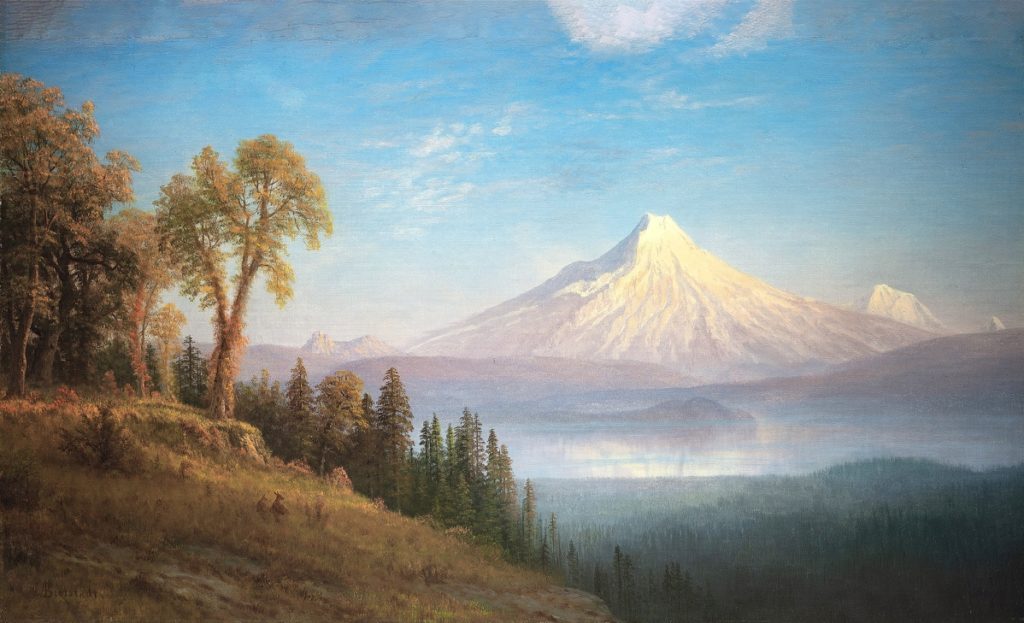

We know that Albert often counseled Charles and Edward in their stereographic practice, advising them on where to place their special, dual-lensed stereographic camera and how to take advantage of light and shadow to “compose” attractive, harmonious images, especially those of the American landscape, many of whose features would have been new and exciting to viewers. Indeed, early photographers often worked to achieve painterly effects, believing that emulating painting would ease apprehension about the science and validate the medium as an art form. At the same time, as the works in the exhibition demonstrate, you can see Albert trying to achieve the dimensionality of the stereograph, but in paint. This is not a new argument. In her 2013 essay in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, “Seeing in Stereo: Albert Bierstadt and the Stereographic Landscape,” Dr Kirsten Jensen discusses the aesthetic of the advent of the handheld stereoscope, writing that it “brought the image directly to the eye, creating the illusion that there was nothing in between the viewer and the scene; the viewed space became no longer a flat surface with two images pasted on it, but a three-dimensional space that was experienced.” (p. 146) She goes on to write that “Bierstadt [Albert] was attempting to create a visual experience of a painted landscape that replicated the personal experience of the handheld stereograph” (p. 153) and that, in later works, especially those depicting New Hampshire’s White Mountains, that he would crop out “elements of human progress and of national tensions from his landscape in the same manner as they would be eliminated from stereographic views” (p. 158).

“Glenview Facade,” from the “Homes on the Hudson” series by Edward Bierstadt, 1887, artotype. Collection of the Hudson River Museum.

Albert Bierstadt’s “Dawn at Donner Lake, California,” painted circa 1871-73 places the viewer, by my reckoning, in the Donner Pass, a pair of words that still conjures at least a vague historical memory of the Donner Party, who, in 1846, found themselves trapped by snow and ice and resorted to cannibalizing the dead in order to survive. To follow Jensen’s thesis, Bierstadt offers a place that seems never to have seen humanity before the now of the painting. It is a forbidding, treacherous place with only a spiritual wisp of light off the lake in the distance. We see it as if for the first time. What’s more, the way Bierstadt layers the composition from foreground to background, with a limited palette and tight, alternating gradations of light, brings the work closer to the stereographic shades of gray.

For further proof of the interplay between Albert Bierstadt’s facture and the photographic practice of his brothers, compare “The Burning Ship,” painted circa 1865, with the stereoscopic image, “Moonlight Effect, Niagara N.Y.,” circa 1869-73. From the moonglow at the edges of the clouds to the shimmer of the moon’s, not to mention the corresponding fire and fire glow on the water at left, we almost seem to see the scene through a porthole, as it were, or, perhaps, through a stereoscopic viewer. We’re simultaneously as far from J.M.W. Turner’s (1775-1851) burning ships that set the very air ablaze as we are from tightly drawn nautical academic works and illustrations. We’re closer, strangely – at least in experiments with the painterly effects of moonlight – to moodier American painters, proto-modernists like Ralph Albert Blakelock (1847-1919) and Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917) whose paintings compel viewers to make shapes out – both in and of the darkness.

What Albert wanted viewers of his paintings to experience, Charles and Edward wanted to broadcast to the wider world, and especially to the nation’s rising middle class. In addition to American landscape scenery, Charles and Albert sought to capture thrilling moments, such as the tightrope walk across Niagara Falls, which was part of the 1876 Centennial, historic sites like the Statue of Liberty, dedicated in 1886, and views of fancy hotels and lavish residences, including views of Glenview – part of the Hudson River Museum – views which were used to help restore the interior of that Gilded Age mansion. All three brothers, even as they sought to bring an expansive dimensionality to their respective mediums – both in subject matter and form – also sought to make the experience of them feel at least somewhat intimate. It’s a tricky tightrope to travel.

“Mount St Helens, Columbia River, Ore.” by Albert Bierstadt, circa 1889, oil on canvas. Collection of J. Jeffrey and Ann Marie Fox. Image courtesy of Questroyal Fine Art.

One stereograph image which, sadly, is not in the exhibition, is an 1859 Bierstadt Brothers photo of Albert, sitting at an easel working on a small oil that looks as though it might be a study for one of the immense landscapes he painted after his trip West with the Lander Expedition in 1959. Prospective patrons look on as Albert works. On the easel, however, are two images, one of which looks very much like a stereograph of the landscape Bierstadt paints. We don’t know if his brothers accompanied Albert, but we do know he brought back stereoscopic views.

A stereograph of a painter painting a painting of a landscape, a painter taking as reference a stereograph of the landscape he is painting. The infinite regressiveness in this reflexivity is staggering, mirrors mirroring mirrors, revealing dimensions to astute viewers who might well feel that they and they alone, have discovered something, something they can share, or not. An intimacy with the wider world, and within it, is what Twenty-First Century algorithms are built to provide, as illusion blurring into reality. The Bierstadt Brothers sit at a pivotal point, when technology began to flip “Seeing is Believing” into its opposite “Believing is Seeing.” From its first birth pangs, photography wanted us to believe in the truth of its imagery, and we still often do, despite digital manipulations that can morph anything into anything else. Artists in other media soon learned to adapt what they could from photography in order to make viewers believe in the truth of their art. The reactions against realism and the academy – from impressionism to all the isms of abstraction – might also be seen as reactions against photography, attempts to make the invisible visible. “The Bierstadt Brothers: Painting and Photography” might well be the first of many exhibitions that trace the interplay between traditional and technological art forms.

Three brothers sought three dimensions, but there are, as they well knew, more dimensions to seek.

The Hudson River Museum is at 511 Warburton Avenue. For information, 914-963-4550 or www.hrm.org.

.jpg)