The WPU’s signature colors of white, purple and green emulated those used by the Women’s Social and Political Union in Britain. Women’s Political Union pennant, circa 1915. Onondaga Historical Association.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

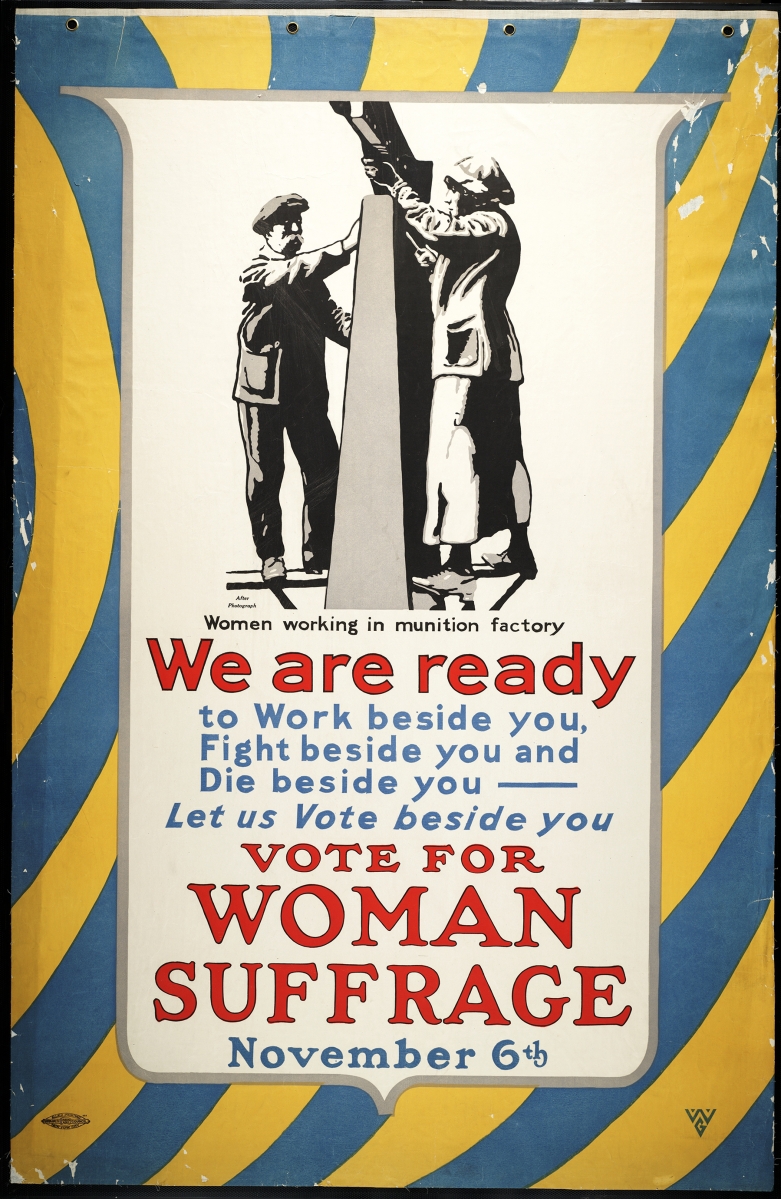

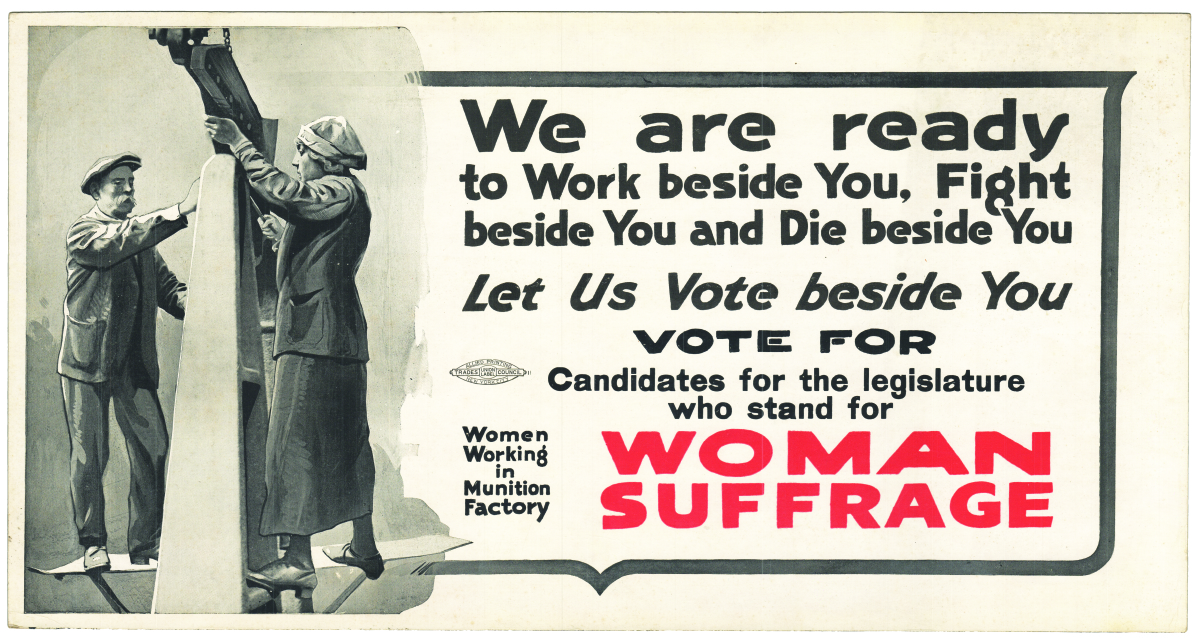

ALBANY, N.Y. — The poster is emblazoned, “We are ready to Work beside you, Fight beside you and Die beside you — Let us Vote beside you. Vote for Woman Suffrage November 6th.” This compelling request, paired with an image of a female munitions factory worker during World War I, was designed to elicit support for New York State’s female suffrage referendum in 1917. The stirring example of persuasive graphic art is one of many emblematic and revealing objects, manuscripts and publications showcased in “Votes for Women, Celebrating New York’s Suffrage Centennial,” open from November 4 through May 13 at Albany’s New York State Museum (NYSM). The exhibition marks the 100th anniversary of the passage of that referendum on November 6, 1917.

While the suffrage crusade is central to this museum presentation, it addresses a far broader range of women’s challenges, responses, successes and failures in the Empire State from time of the American Revolution to the present.

For this large-scale exhibition, co-curators Jennifer A. Lemak, NYSM chief curator of history, and Ashley Hopkins-Benton, NYSM senior historian and curator, have assembled 240 items from 52 institutional and private collections as well as the State Museum’s own holdings. These illustrate significant events and issues in the movement’s history while also serving to personalize it.

In New York State, as in the rest of the United States, the road leading toward gender equality has not been without bumps, twists and turns. Dreams that women’s very limited rights would be expanded as part of the new nation’s founding were not realized and it would take decades for the foundation of the women’s movement to be laid.

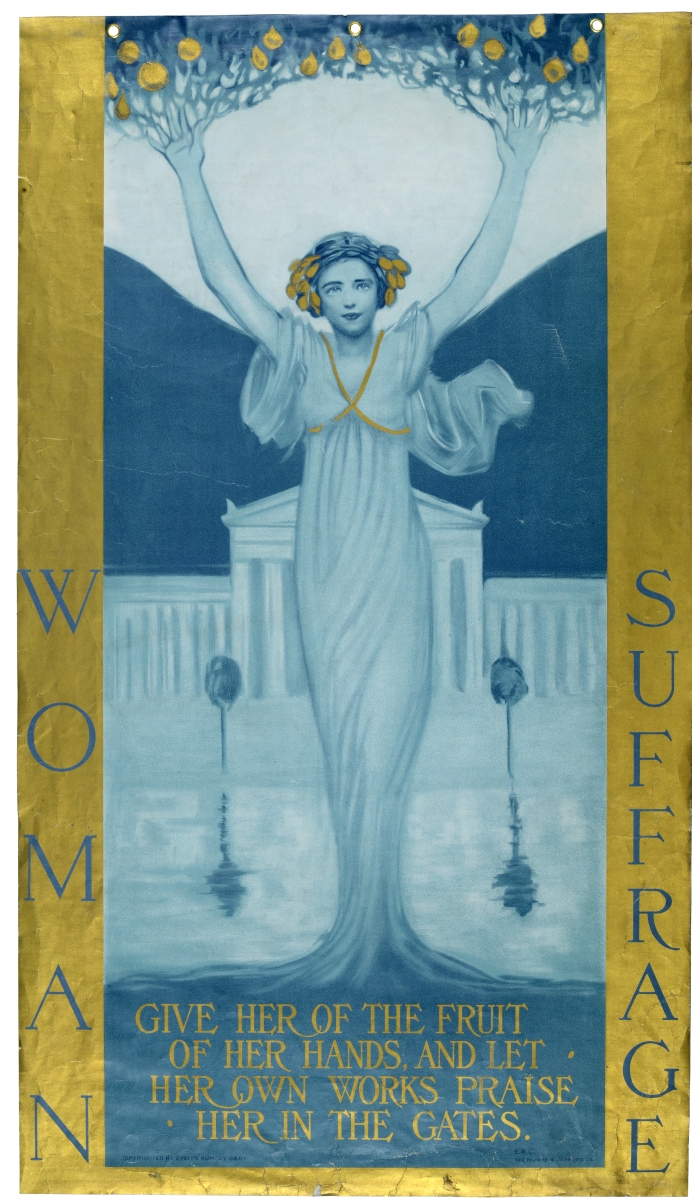

Key in this story was the central and western section of New York State. During the early and middle decades of the Nineteenth Century, the region was marked by a strong reform spirit and desire to perfect society. This optimistic striving has been linked to the forward-thinking New Englanders who migrated there in the post-Revolutionary War era and to waves of religious revival. The area proved a particularly fertile ground for champions of the abolition of slavery, suffrage for African American men, educational reforms, experiments in utopian living, and suffrage and greater rights for women.

Historians generally consider a meeting held at the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls, N.Y., on July 19 and 20, 1848, as the official birth of the women’s rights movement in the United States. The Seneca Falls Convention with its Declaration of Sentiments and Grievances echoed the Second Continental Congress’s gathering at Independence Hall and the creation of the Declaration of Independence. Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815–1902) and Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906) — along with a legion of less famous believers — harnessed the power of the pen, the lectern and the volunteer association to promote their platform.

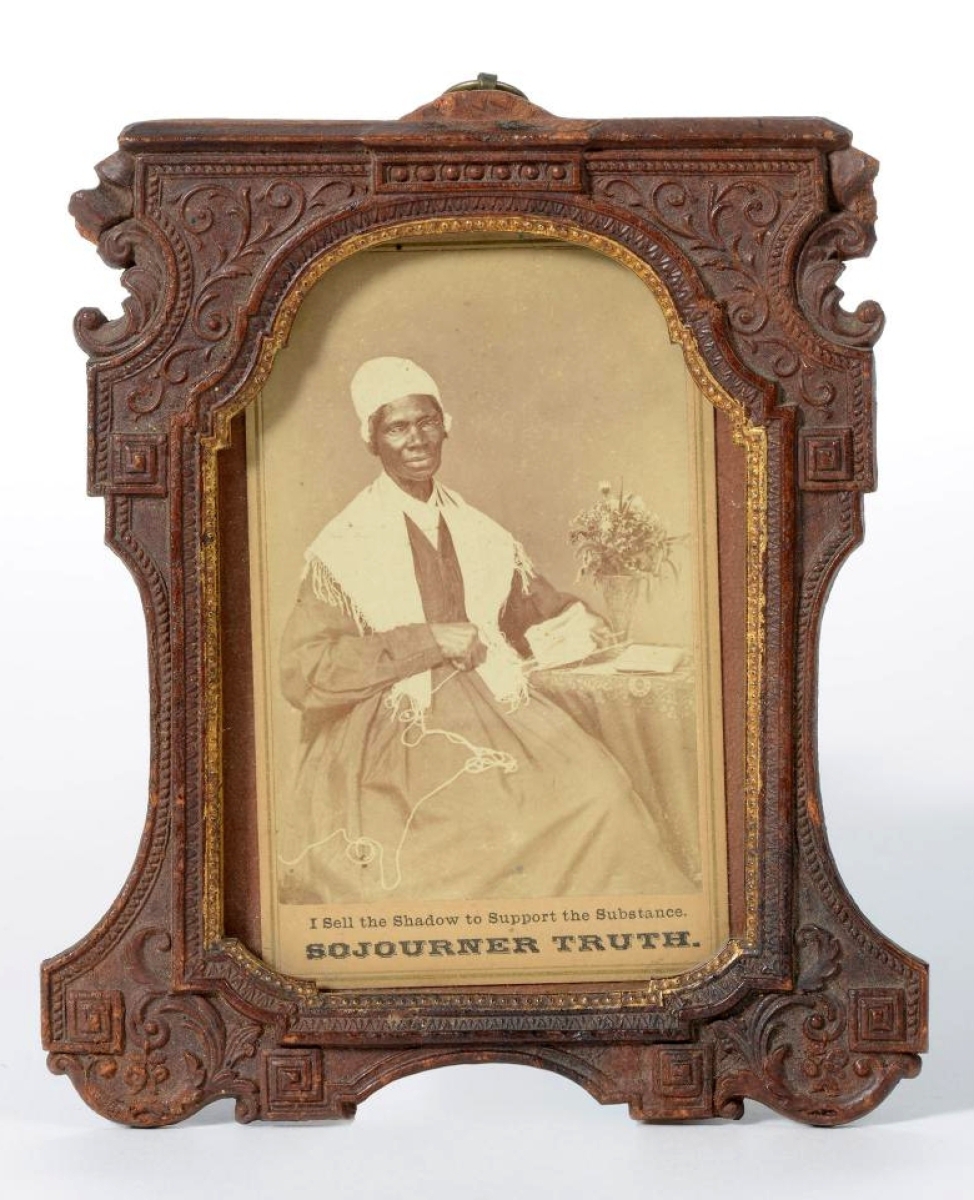

Hopkins-Benton pointed out that, even in these early years, winning the vote was just the tip of the wedge. Proponents led with suffrage even as they sought other legal rights, including those involving property ownership and marriage; greater educational, business and professional opportunities; and other freedoms. Lemak underscored how organized the women were from the start. The movement was “planned by educated women who knew what they wanted to achieve.”

Shirley Chisholm (1924–2005) was the first African American woman elected to Congress. The year was 1968. She ran for the United States presidency four years later. Bella Abzug (1920–1998) first won a seat in Congress in 1971. Chisholm and Abzug campaign buttons in a shadow box, circa 1970. Courtesy of Ronnie Lapinsky Sax.

The battle to allow women entry to the polls intensified during the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries. Coordinators enlisted and mobilized followers via various strategies. They started suffrage groups and distributed promotional publications and paraphernalia. They pursued activities that are still staples of political action and campaigning today — door-to-door canvassing, gathering signatures on petitions, writing articles and letters to the editor, hosting fundraising events, marching in parades and mounting attention-grabbing demonstrations in symbolic places and spaces.

Lemak summed up the importance of the 1917 New York victory. “Passage of women’s suffrage in New York State was the national suffrage movement’s first electoral triumph east of the Mississippi River. The Empire State carried 47 electoral votes and assured 45 seats in the US House of Representatives. Suffrage in New York State signaled that the national passage of suffrage would soon follow. In August 1920, ‘Votes for Women’ was constitutionally guaranteed.”

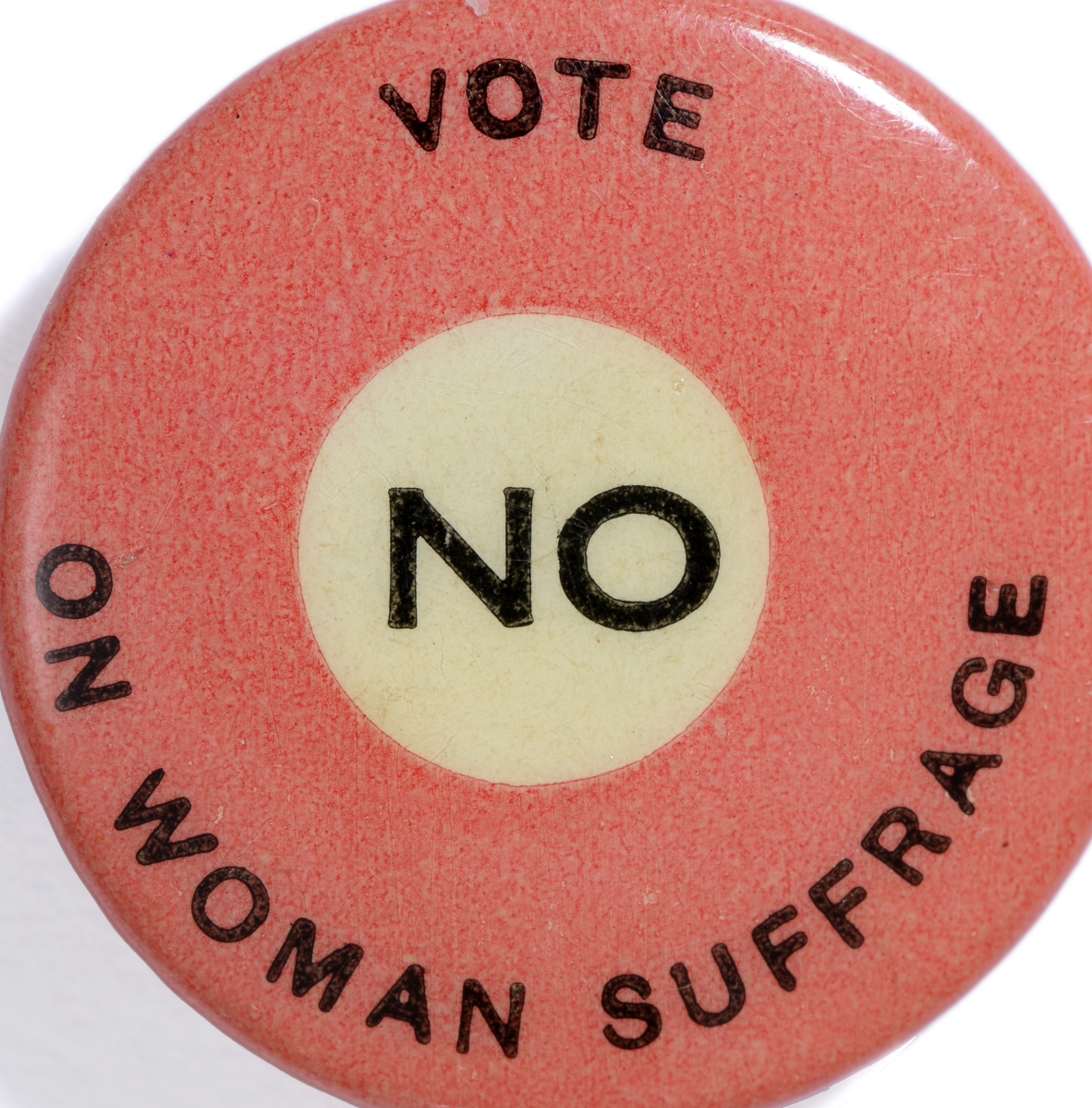

As with nearly all historical events, the cause of women’s suffrage was influenced by some choices and happenstances that give one pause today. For instance, in the mid-1860s, Stanton and Anthony appeared on the lecture circuit with George Francis Train, a racist who promoted white female suffrage as a counterweight to African American male suffrage. In general, the traditionally upper and middle class white campaigners for women’s voting rights did not eagerly open their suffrage clubs’ doors to African American and working-class women. There were also the men and women driven by diverse beliefs and fears who assumed an anti-suffrage stance.

The last section of the exhibition picks up the story after the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. Topics include the Equal Rights Amendment, still unratified, which was first introduced in the United States Congress in 1923; the Feminist movement with its work, financial, family and personal freedom components; and the contributions of New York female politicians, including Shirley Chisholm (1924–2005) and Bella Abzug (1920–1998). Stated Lemak, “We wanted to bring the struggle for equality up to the present day. It did not end with winning the right to vote.”

The richly illustrated companion book co-edited by Lemak and Hopkins-Benton contains their master narrative along with a series of monographic essays authored by consultant scholars. Published by the State University of New York Press, Albany, the volume will be extremely useful to those teaching and studying women’s history in high schools and colleges.

Because women’s suffrage organizations generally did not welcome black women as members, they formed their own groups. Begun in 1899, this club was an affiliate of the National Association of Colored Women. It was named for the first African American poet to be published. Phyllis Wheatley Club, Buffalo, N.Y. Library of Congress.

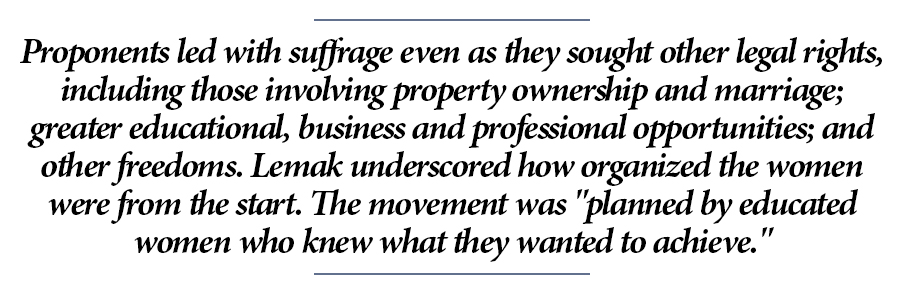

Collectors and material culture specialists are likely to be intrigued by suffragists’ skillful exploitation of the “propaganda arts” in proclaiming and reinforcing the message. With the development and proliferation of mass-produced commemoratives and souvenirs during the late Nineteenth Century, recruits in the women’s suffrage army wore, wielded and waved sashes, ribbons, badges, buttons, spoons, umbrellas, fans, pennants, flags and other “novelties” of the sort deployed by political parties and fraternal organizations. They were cheered by posters, car cards, banners, sheet music, postcards and illustrations in newspapers and magazines.

Lemak observed that major collectors of suffrage memorabilia have loaned some of their most important material to the exhibition. One of these generous supporters is Coline Jenkins, the great-great-granddaughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Her family’s ongoing commitment to achieving parity between the sexes is illustrated by artifacts representing various members’ interests and affiliations through the generations.

Another is Ronnie Lapinsky Sax, the long-serving president of the Women’s Suffrage and Political Issues chapter of the American Political Items Collectors (WSAPIC) who shared 68 articles from her personal collection. By day a senior portfolio management director and senior vice president at Morgan Stanley Wealth Management, she characterized her pursuit and acquisition of historical resources connected to the women’s movement as a “40-year labor of real love” that has resulted in a trove of some 5,000 items.

Asked what these objects meant to suffragists at the time, Sax characterized the badges, ribbons and related insignia as “proud proof of how they felt, near pieces of jewelry.” She went on, however, to explain that in the late 1800s women carefully chose where and when to wear them so that they would not “be ridiculed and ostracized.”

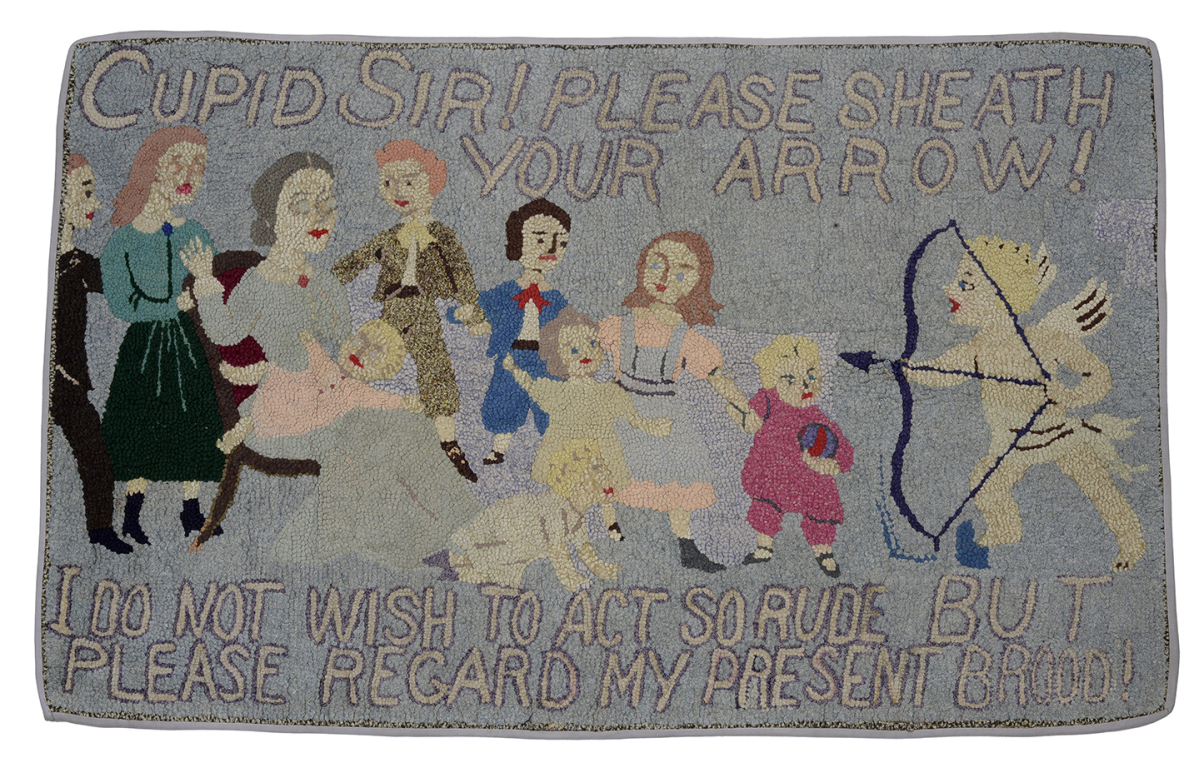

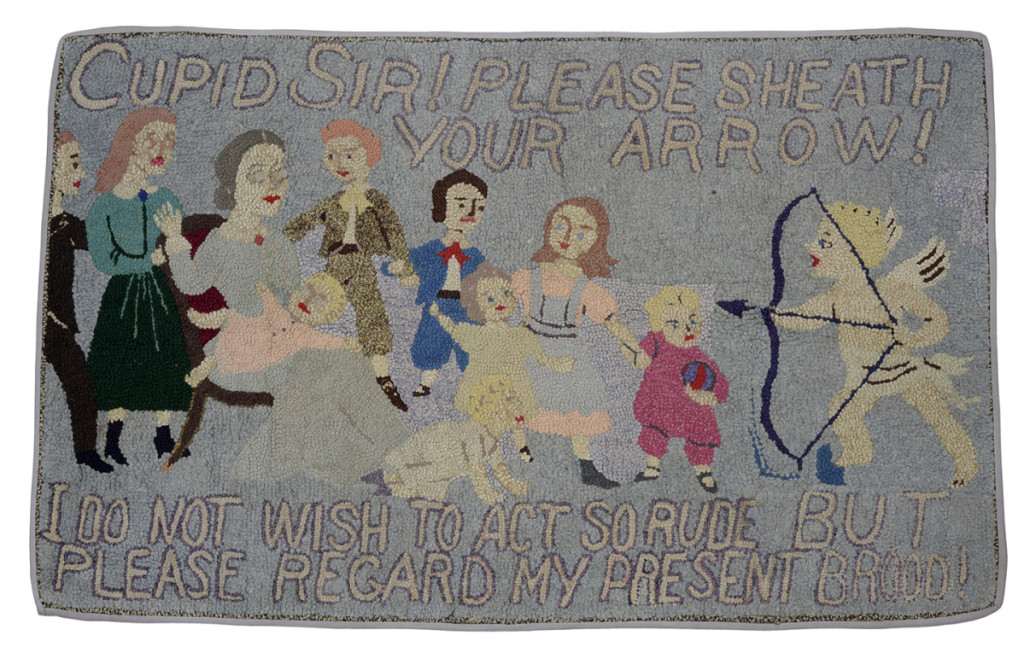

This hand-fashioned floor covering with its birth control message is among the unexpected artifacts on display. Beginning in the 1870s, condoms and other birth control devices appeared with some frequency in advertisements. Hooked rug, circa 1910–1940. Dorothy Hamilton Brush Collection, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College.

Regarding “activist” memorabilia overall, this sage collector observed that “material manufactured to change policy outweighs the material manufactured to just stay the course.” In this case, promotional items created to further greater rights for women are more plentiful than objects encouraging the status quo.

As with other social justice movements now on the “right side of history,” it is easy to forget that female suffrage was not inevitable nor quickly won. Advocates in New York were in the vanguard, buoyed by various kinds of support while also facing strong opposition from sundry quarters. As New York’s successful 1917 referendum set the stage for the adoption of Nineteenth Amendment nationwide in 1920, “Votes for Women” will serve as a valuable model for similar centenary exhibitions in the coming years.

The 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage in New York has been marked by a substantial roster of exhibitions and programming mounted across the state and throughout the year. Select exhibitions currently on view include “Hotbed,” an exploration of the connections between Greenwich Village art, life, politics and culture and the suffrage movement. It runs from November 3–March 25 at New-York Historical Society. Through this December, visitors can tour “Votes for New York Women, A Centennial Exhibit” at the Suffolk County Historical Society Museum and “Woman’s Protest: Two Sides of the Fight for Suffrage in New York” at the Cayuga Museum of History and Art. “Beyond Suffrage: A Century of Women and Politics in New York” can be seen through July 22 at the Museum of the City of New York.

The New York State Museum is at 222 Madison Avenue. For information, 518-474-5877 or www.nysm.nysed.gov.

Kate Eagen Johnson is an expert in American decorative arts and an independent museum consultant, historian, lecturer and author.