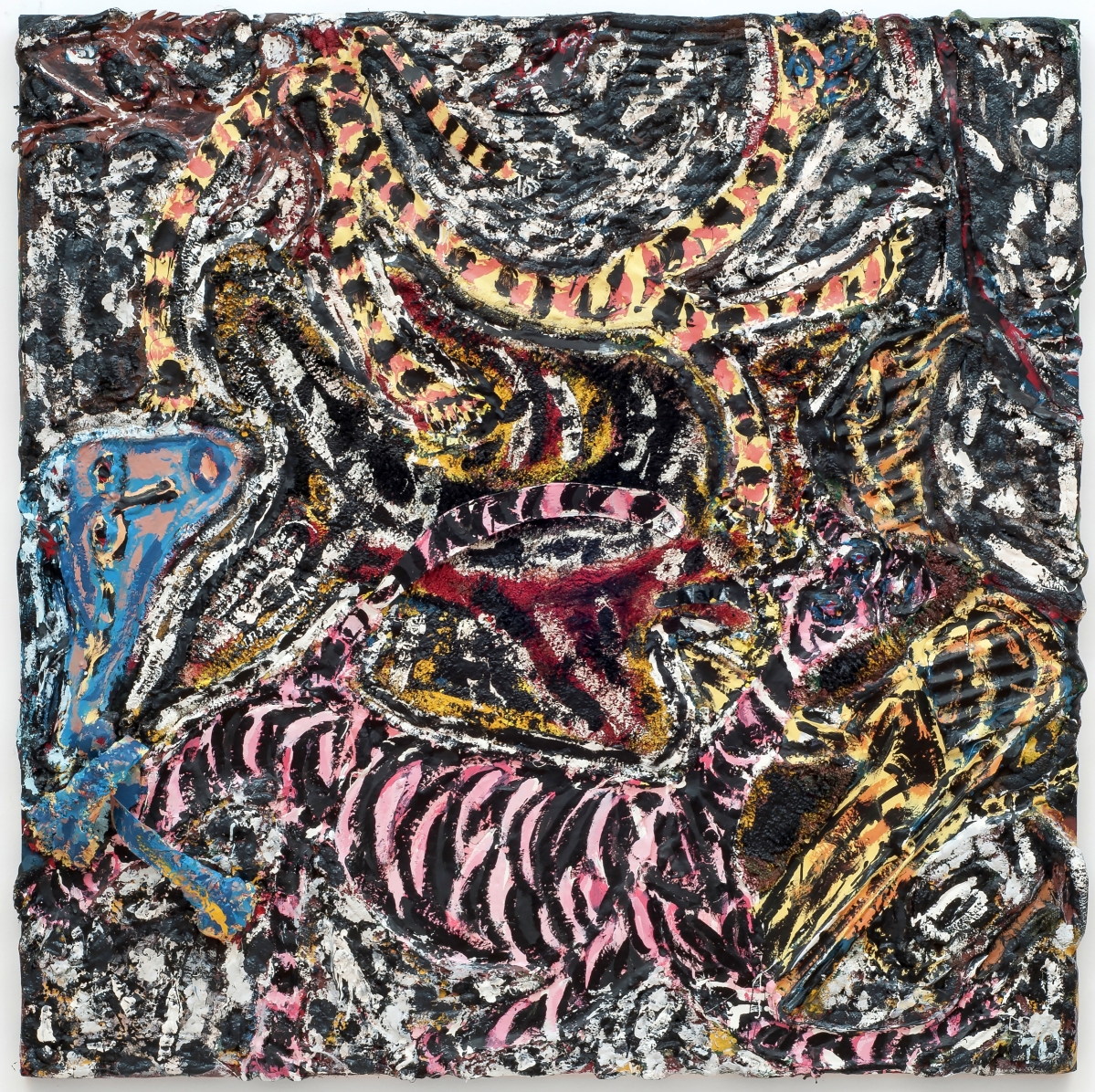

“James Harold Jennings, Pinnacle, NC” by Roger Manley (American, b 1952), 1988. Courtesy of the artist and Institute 193. ©Roger Manley.

By James Balestrieri

As an antidote to making the often funereal rounds of galleries and auctions, museums and shows, the idea of a road trip into the hinterlands in search of folks who make art because they want to (read: because they must) and punctuating these “this-car-brakes-for-art” stops with good music and great barbecue has all the makings of a real tonic (with a squeeze of lime and a splash of bathtub gin, just to be sociable). This is the inviting premise of the High Museum of Art’s new exhibition, “Way Out There: The Art of Southern Backroads.” What is even more intriguing is that this exhibition is built on an all but forgotten manuscript titled Walks to the Paradise Garden: A Lowdown Southern Odyssey, written by poet Jonathan Williams and published now by Institute 193. Illustrated with incredible photographs by Guy Mendes and Roger Manley, the book chronicles a series of road trips Williams, Mendes and Manley took in the 1980s-90s. On these trips, they paid visits to a number of famous names in self-taught art, including Eddie Owens Martin (“St EOM”), Thornton Dial, Edgar Tolson, Georgia Blizzard, Sister Gertrude Morgan, Howard Finster and others.

Many of these artists not only made art, they made their visionary world views into worlds that they inhabited, worlds made of art. The photographs, in these instances, offer crucial insights into the spiritual wellsprings of their aesthetic approaches and their artistic practice. As well as the photographs, installations will recreate pieces of the environments that these artists created as sanctuaries and incubators.

I have written in the past in these pages about outsider and outlier artists, folk artists, autodidactic (self-taught) artists, vanguard artists, and I have tried to tread carefully when dealing with categories that might seem to privilege academic training or the urban artist’s elite progression from school and street to gallery and museum. The truth is, I am not wild about any of these names, not because I am interested in leveling the field, but because these distinctions limit and thereby do damage both to the artist who moves through traditional channels and the artist who stakes out the exclusive territory of his or her own imagination. “Way Out There,” the name of this exhibition, implies a “Deep In There,” conjuring some silent coastal city gallery with large, splashy works on stark white walls and an expensive espresso machine for frequent buyers. My own first paragraph here sets up this opposition.

But none of it is real. Or do I mean that all of it is real? Look at the works in “Way Out There: The Art of Southern Backroads” and read some of the text on the walls taken from Walks to the Paradise Garden: A Lowdown Southern Odyssey.

Eddie Owens Martin, who called himself St EOM, built a temple to a personal religion, Pasaquoyanism, which came to him through the medium of spirits that appeared when he was ill and when he was hustling in Harlem and Midtown Manhattan, far from his Marion County, Georgia home. Pasaquoyanism has something to do with keeping your hair and beard groomed, and “levitation,” and fortune telling, but most of all, according to St EOM, we should all “just act natural,” in and with the natural world and one another. But we shouldn’t fool ourselves into thinking he was just a crazy artist or that he was real, whatever that means. He called himself “a Prophet without profit,” and fretted that his temple complex and his philosophy would die with him. “Rednecks never sleep and order drifts towards chaos,” St EOM observed, not without his own species of worldly wisdom.

Guy Mendes’ Kodachrome photo, “Front Gate, Land of Pasaquan” and St EOM’s polychrome bust, “Pasaquoyan Man with Ritual Headdress and Levitation Suit,” offer ways into the artist’s imagination. You want to connect image and sculpture to the arts of traditional cultures, to the totem poles of the Haida, perhaps, or the carved war clubs of New Caledonia, but the connections don’t take. There is as much of the carnival and sideshow here, as much advertising for an unexpected roadside attraction as there is of indigenous artforms. Just imagine the beads that line the “Pasaquoyan Man’s Headdress,” for example, as light bulbs. But that interpretation would be just fine with St EOM, whose note to Williams in 1977, reproduced in the accompanying text, sums up the artist’s joyous contrarian iconoclasm: “The weather is lovely this morning as I write this letter to you. Makes one happy to be alive. Even if it’s not in the plans and the pranks of the bureaucracy in Washington and in Atlanta, let’s be up with Pasaquoyanism! And may the old mores change for the better! I will have some collard greens for you when you come next time. Sin!! EOM.”

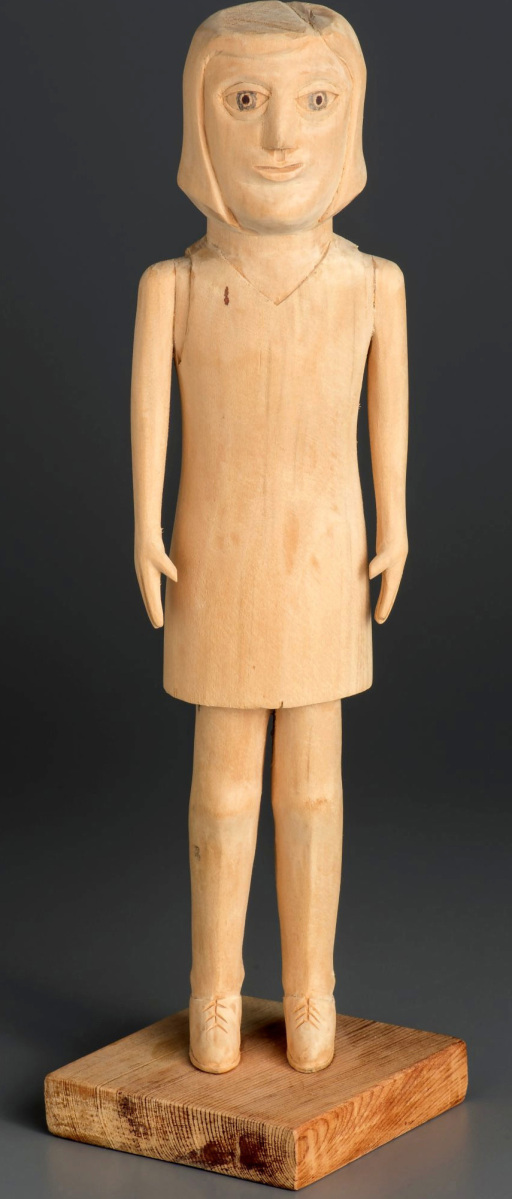

Cobbler, coal miner, preacher: these are only three of the jobs Appalachian artist Edgar Tolson did to make ends meet for him, his wife, and his 18 children. Above all, Tolson was driven to whittle, carving figures in a severe, totemic style that recalls the earliest classical Greek sculptures, works like “Kritios Boy.” Often retelling the story of Adam and Eve and the Fall of Man, all of Tolson’s carvings stare back at the viewer in direct indictment. Even a secular work such as “Untitled (Figure of a Woman)” finds the viewer complicit, implicated in the weakness and sin that binds us all. Williams writes: “The day Edgar posed next to his studio, he told Guy about the recurrent drunk dream in which his dolls come to life and march in to surround him, saying, ‘You made me! You made me!’ Hundreds of small pale dolls with their blank expressions and wide, unflinching eyes, flanked by 18 children and umpteen grandchildren, with mess in their pants and dirt on their faces, all pointing their stubby little digits up at Tolson, confronting him with his deeds. ‘You made me! You made me!’ Edgar’s eyes then go out of focus and he says, ‘I can’t never figure out what they want me to do about it.'” Creation is compulsion, Tolson and his carvings seem to say. Creation cannot be helped. There is nothing to be done.

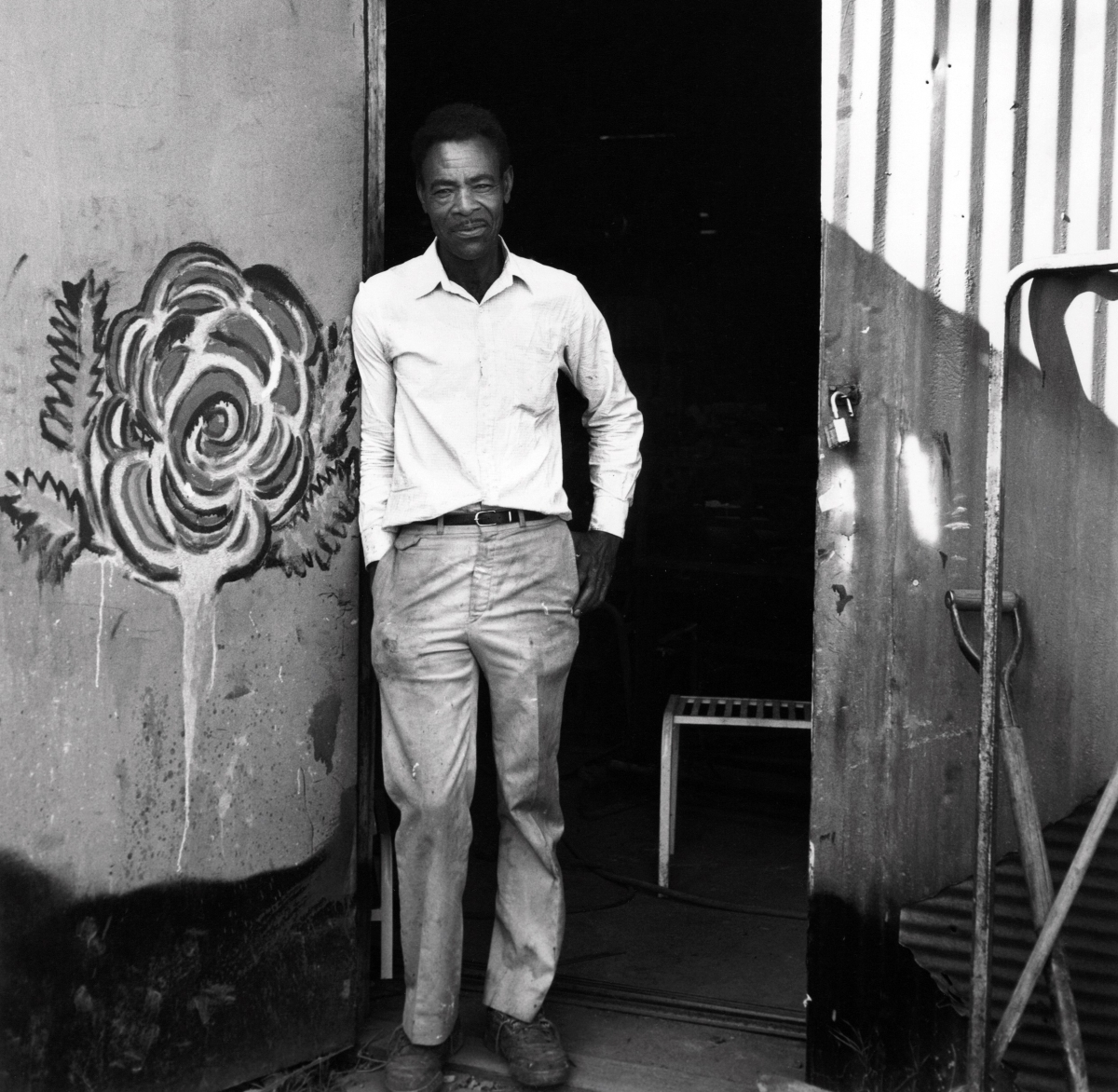

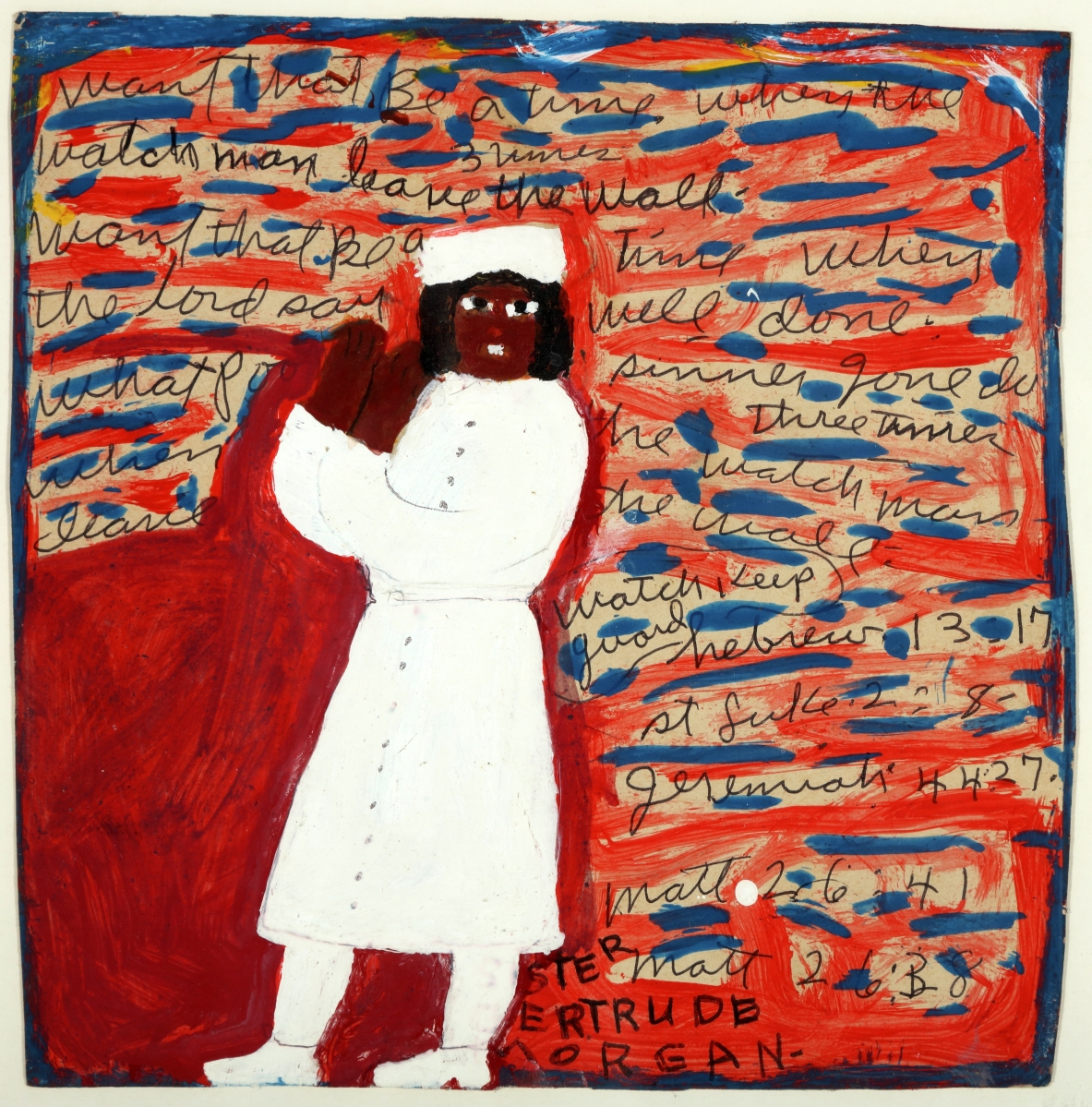

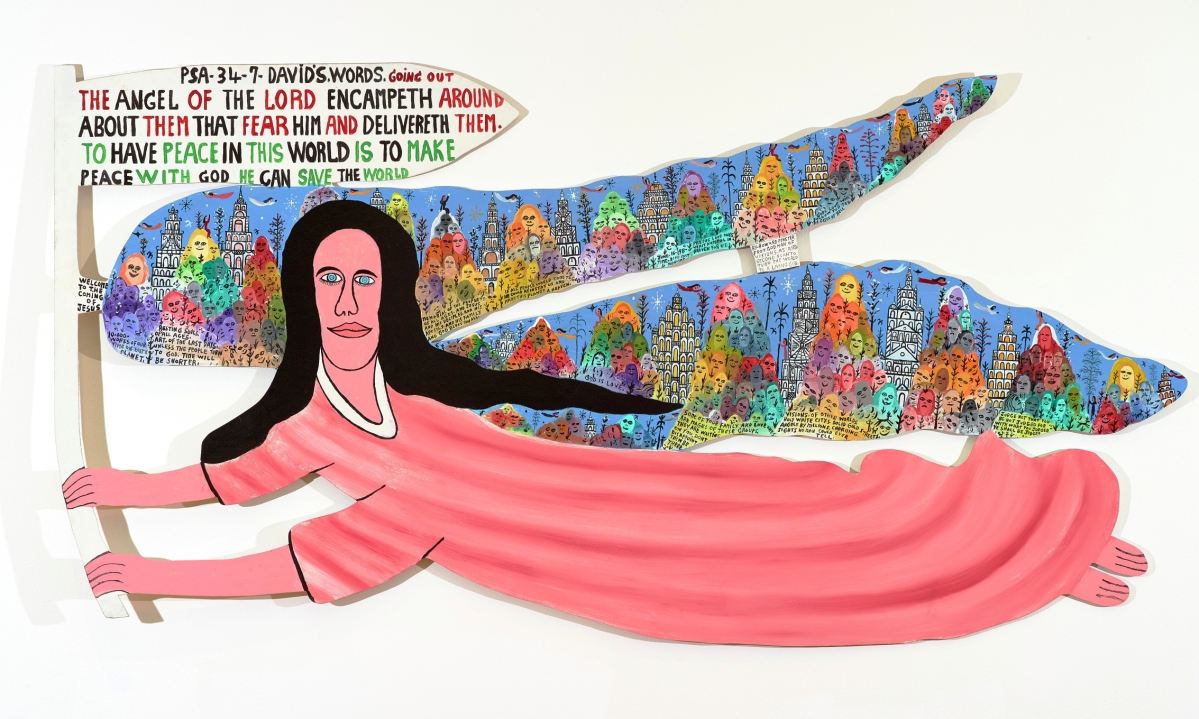

Well-known self-taught artists Sister Gertrude Morgan and Howard Finster, whose works are part of the exhibition, may find their avocation in the realm of Christian revivalism, but their passion is no less fervent for its familiarity. In the works of each, passages from scripture surround the figures like living clouds. A need to spread the Good Word, to make it manifest, gives rise to the impulse to create art. Where message precedes creation, art is functional, though instead of talking about the aesthetics, say, of industrial design, function here is purely spiritual, exhorting us to repent, to seek peace, to know God.

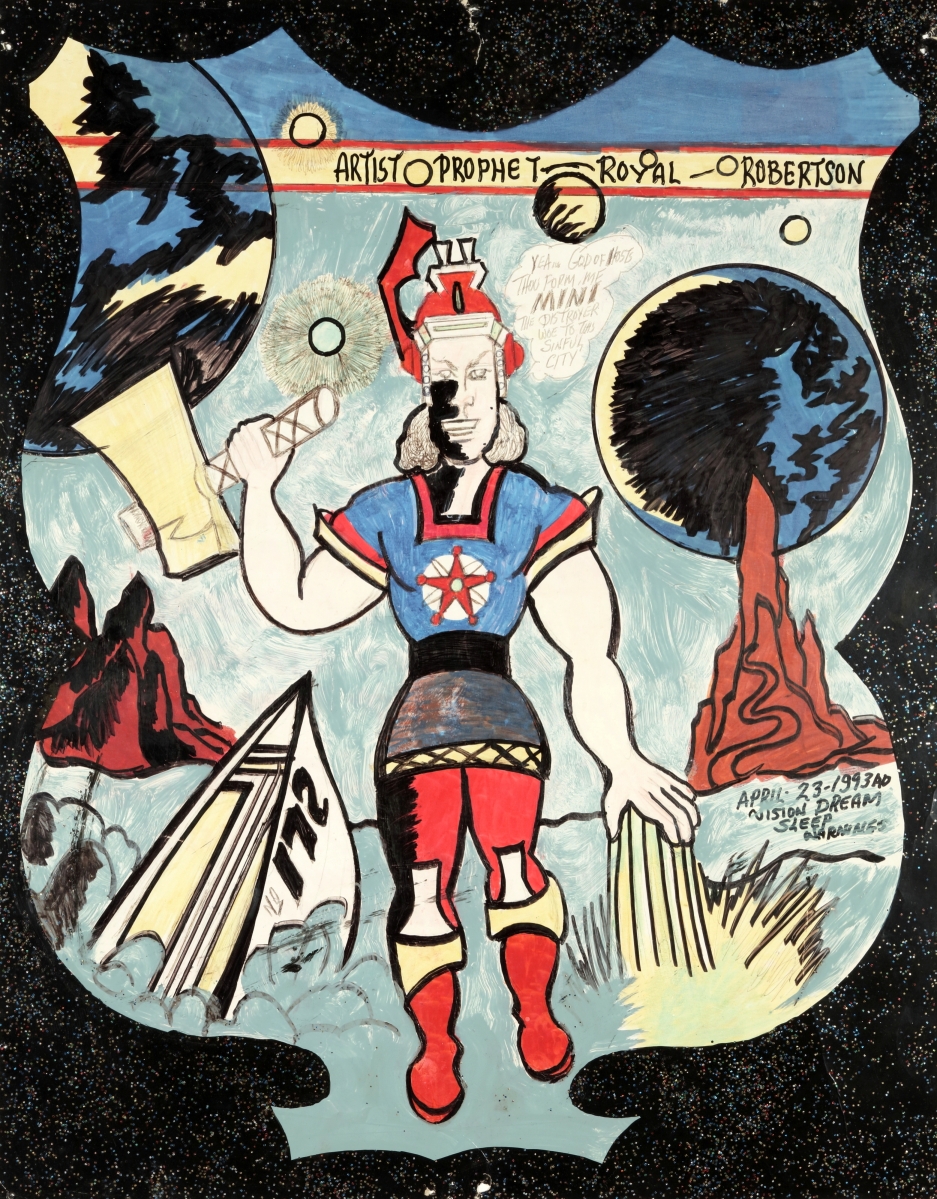

Royal Robertson’s visionary work combines Christian eschatology with science fiction and superhero themes. In “Vision Dream,” Mini the Distroyer, a hybrid of Marvel’s Thor and Robertson’s imagination, wields a world-killing hammer and vows “woe to this sinful city.” Robertson suffered from paranoia, and when his wife left him for another man, he transformed his sufferings and betrayal into a delirious body of work that would come to fill his home.

Finding a space and filling that space with art is an important aspect not only of this exhibition but of self-taught or outsider art in general. If, for the artist, there is a division between home, studio, gallery and museum, the artists here destroy these categories, merging them into a single entity. Mary T. Smith’s paintings on snipped fragments of discarded corrugated tin, portraits of Jesus and the angels, family and visitors, became the fence around her house, became the materials that comprised the outbuildings inside the fence, and decorated every square inch of the walls of her dwelling. Their simplicity belies their impact. Often compared to Byzantine icons, her portraits are also reminiscent of Fayum mummy portraits, staring out at you from eternity, from an afterlife on the other side that makes you wonder who they were and, eerily, where they might be now.

The 7-acre Land of Pasaquan was the visionary environment of Eddie Owens Martin (St EOM). “Front Gate, Land of Pasaquan, near Buena Vista, GA” by Guy Mendes (American, b 1948), 1982. Pigmented inkjet print. Courtesy of the artist and Institute 193. ©Guy Mendes.

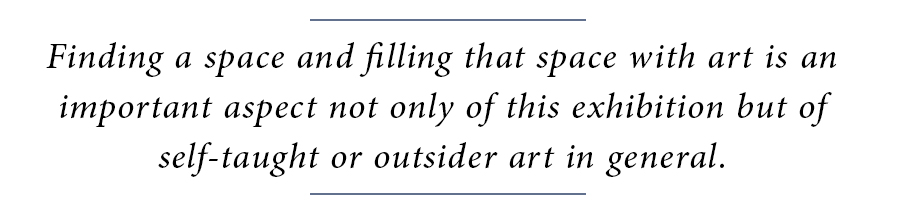

If you want to break even more boundaries, after you view “Way Out There: The Art of Southern Backroads,” have a stroll through “Hand to Hand: Southern Craft of the 19th Century.” Look especially at some of the quilts and then circle back to Thornton Dial’s “Proud Cats Made to Climb” in “Way Out There.” Consider Dial’s materials: carpet and rope as well as paint, metal, canvas and wood. “Proud Cats Made to Climb” is as woven a work as any quilt, where the cats themselves are like frayed and knotted ropes. At left, a creature with a human face stretches its neck and face upward, yearning to escape the maelstrom, a rough, stormy tapestry of black and white. A group of lions is called a pride, and pride goeth before a fall. This pride of proud cats has fallen and now must climb. Meaning here is elusive, but the work might well be a meditation on class and inequality, or on human hubris in its many forms, even the hubris that comes from daring to make art.

Art rises from a dual sense of detachment from the world and a profound need to examine and express that detachment and the reasons that give rise to the gulf. The tissue that connects the artists in this exhibition, the thing that, perhaps, makes it most attractive, is the absence of irony, an absence that can only accompany a measure of spiritual certainty. This is art without “art,” without artfulness, hearkening atavistically to the stonemasons and stained glass masters of Chartres, to the mosaics of Monreale, to the lions of Assyria. This is art before art, art that springs from belief, from faith.

This is too simple, perhaps. Write a word on a page, scratch a quarter note onto a staff, daub a single daub of paint onto canvas, and you instantly find yourself in the wilderness. Whatever maps you thought would help you traverse it evaporate. The next word, note, stroke, is a mystery beyond “authenticity” and “artifice,” words belonging to the critics’ vocabulary that have nothing to do with creation. You must commit. Tell me, what’s the difference, whether you are classically trained or going on instinct? Sweat is sweat. Whether your taste runs to espresso or barbecue – or both – the act of art is an act of faith.

The High Museum of Art is at 1280 Peachtree Street NE, in Atlanta, Ga. For more information, 404-733-4400 or www.high.org.