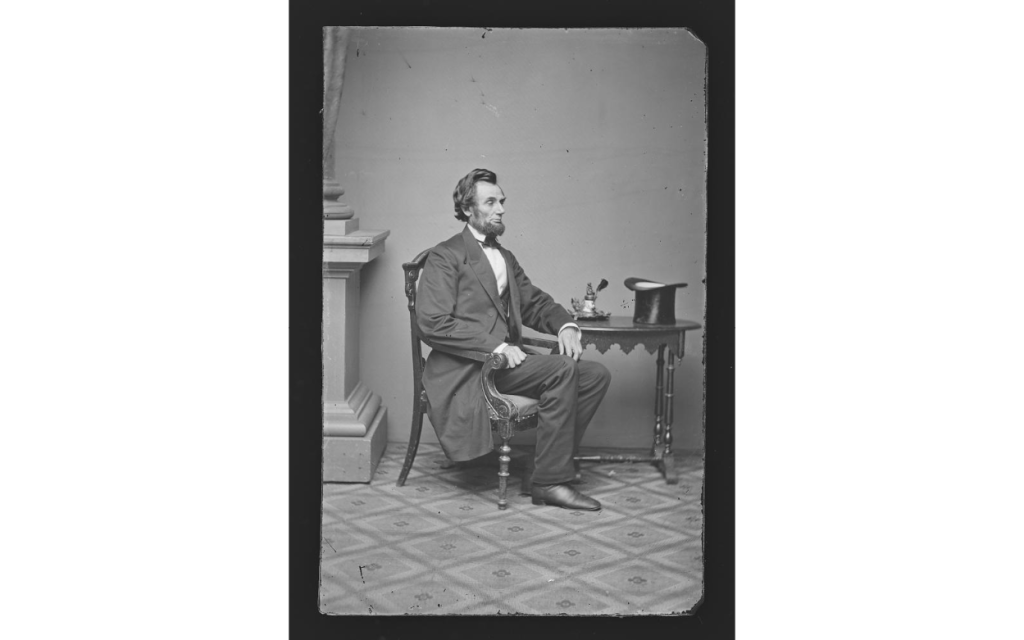

Studio portrait of Abraham Lincoln, photographed by Alexander Gardner (1821-1882). Glass plate collodion negative. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Frederick Hill Meserve Collection.

By Greg Smith

[Ed note: Dr Samuel Wheeler’s December 16, 2019, report, which is cited heavily as the primary source for this article, is available at www2.illinois.gov/alplm/museum/About/news/Pages/HatResearchUpdate.aspx]

SPRINGFIELD, ILL. — The success of any modern museum is rooted in showmanship. This is why curators don’t plop a few objects with corresponding placards in a case and call it a day. They hire designers and spend money to create a show, a visual the likes of which the public has never seen before — an environment dreamt up with the sole aim of driving attendance and proffering importance. The public demands to be wowed. Shower us in splendor and make us feel the rapture of life. Expand our knowledge of what is possible and inspire the imagination to pursue the infinite. Give us the truth of our past so we can better understand the present.

Truth.

Truth is the cornerstone of any historical museum and library. These particular institutions — the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum (ALPLM) is one of many in the United States — are dedicated to preserving history through collections of objects and documents, and committed to disseminating information through the programming of both permanent and temporary exhibitions. The material in the ALPLM’s collection is a resource for researchers around the world as they continue to develop understanding.

Like any other museum’s collection, the ALPLM’s is the nucleus of its being. That collection stretches back to 1889, when state historians began preserving documents relevant to Illinois history. This was solidified in 1903, when establishment of the Illinois State Historical Library (ISHL) was signed into law. Current Illinois state historian Dr Wheeler characterizes the collecting habits of the library over its first century as being focused on documents, as opposed to three-dimensional objects. It was a library, after all. When the ALPLM opened, it incorporated into its collection the 12 million items in the ISHL’s collections, most of them books, newspapers and printed material.

American political memorabilia and document collecting took flight in the second half of the Twentieth Century. These works, which together tell the story of the country’s trajectory through time, include campaign items, artifacts of presidential life, historical documents written by and surrounding the notable figures in the political spectrum, and personal effects. By nature of their three-dimensionality, they illustrate the context of life at large and the moment of their creation. Their existence gives an opportunity to contextualize and educate, like eternal teachers — to allow the words that are so often taught in textbooks to spring to life and jump off the page.

Breaking down the different categories of political memorabilia, dealers and curators are apt to point out strengths and shortcomings in each. Documents, for instance, are fairly straightforward to validate by a professional. Does the signature match? Do the curves of the letter y match a figure’s known handwriting style? Is the paper correct? And the ink? That is not to say there aren’t disagreements between the experts on these, but they are few and far between when compared to the most fraught category of political memorabilia: personal effects.

The very issue with touting a claim that x belonged to y, or a stovepipe hat belonged to Lincoln, is that there is hardly ever any thorough evidence to support it. There is almost always — nearly every single time — a leap of faith.

But collectors, dealers and curators of this material understand this with certainty, and scrutiny is a common conversation in the field. Due diligence and research are the norms. Throw your assumptions out the window: Where do the facts lead?

When the ALPLM opened in 2005, politicians from across the aisle gathered to inaugurate the new home of America’s most celebrated president. The ceremony projected the great promise that this new institution would offer, building on the message that Lincoln’s resolute character was eternal and a beacon of progress. Illinois State and United States Congressmen gathered to dedicate this monument to truth, with words shared from Dick Durbin, Ray LaHood, Barack Obama, Dennis Hastert, Illinois Governor Blagojevich and President George W. Bush.

In the eyes of all, this was a coup. They had arrived. There was a sense that the ALPLM had crested the peak after a long uphill journey that began seven years earlier.

It felt that way because even in its early stages, the project was dogged by bureaucratic and political controversy.

In 2002, Illinois state legislators approved $20 million for the destruction of buildings on adjacent streets to the museum, some of them historic themselves, with the intention to create a vista or a mall around the property. The community rose up, protesting that the destruction of history in a pseudo-attempt to memorialize history was a poor argument. The buildings still stand.

Famously, Illinois Senator Peter Fitzgerald filibustered the Congressional bill that would have appropriated $50 million in federal funds for the library, opposing it on the grounds that the developers were chosen in a no-bid process. He said, “I want Illinois to get a $150 million library, not a $50 million library that just happens to cost $150 million.” Fitzgerald retired after his one term, and Obama stepped into his seat. The initial $40 million cost estimate finished at $141.9 million, but only following the settlement of a series of lawsuits filed by the state to avoid paying its contractors overruns, effectively sidestepping $7 million in costs it felt was not its responsibility.

Funds for construction came from all levels: Fitzgerald’s filibuster cost the project $17.7 million as Congress ultimately appropriated only $32.3 million, another $101 million came from the state of Illinois and there was $8.6 million from the city of Springfield.

More funds would be needed for acquisitions and programming. For this, the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation (ALPLF) was established, a private 501(c)(3) charitable organization serving as the principal fundraising body for the ALPLM. It supports the educational and cultural programming of the ALPLM, fosters Lincoln scholarship through the acquisition and publication of documentary materials relating to Lincoln and his era and promotes a greater appreciation of history through exhibits, conferences, publications, online services and other activities designed to promote historical literacy. The ALPLM is required by law to work with the ALPLF.

Dr Wheeler’s December 16 report titled “Provenance Research on the Stovepipe Hat (TLR 001)” all but offers a conclusion on whether Abraham Lincoln owned the stovepipe hat purchased from Lincolniana collector and former ALPLF board member Louise Taper. It does specifically provide a synopsis of the Taper acquisition and the manner in which it was structured; an examination of the relationships between then-Illinois state historian Dr Schwartz, former curator of the Lincoln collection at the Illinois State Historical Library James T. Hickey and noted Lincolniana collector and Lincoln scholar Louise Taper, which amounted to a heap of conflicts of interest; an admission that Dr Schwartz had not performed professional-level research on the collection prior to recommending its purchase for $23 million, nor had any other curator or historian at the ALPLM; and, finally, the revelation that the ALPLM promoted “untruths” in defense of the top hat purchase, compromising its integrity as an authority of material relating to the life of Abraham Lincoln. Wheeler’s report also includes his research into the life of William Waller, whose wife, Clara Waller, provided the first written document linking the ALPLM’s top hat to Lincoln in 1958.

Track back to the museum’s planning phases, and Dr Wheeler notes that Dr Schwartz began raising concerns that the ALPLM collection was not good enough. “The core of the ISHL collection had been growing since 1889, but it mostly consisted of paper items,” Wheeler writes. “The library had never considered three-dimensional artifacts a priority. A world-class museum, however, would require regular artifact rotations and new items to put on display to encourage repeat visitation.”

In lieu of owning major artifacts relating to the life of Lincoln, and not content with a show of paper signatures, Dr Schwartz secured two of Taper’s most prized possessions for loan as the museum opened: Lincoln’s stovepipe hat and a copy of Lincoln’s handwritten Gettysburg Address.

Six months after the opening, Taper says she’ll sell her collection to the ALPLF. Taper’s collection was renowned by this point: 1,500 world-class objects that she had plucked from major dealers and auction houses over two decades of buying, items that included Lincoln’s handwritten documents, artifacts from his personal life, the blood-stained gloves he carried the night of his assassination and many more.

Dr Schwartz told Antiques and The Arts Weekly that the ALPLF approached Taper with this proposition, and not the other way around.

Throughout the ensuing negotiations, Dr Wheeler repeatedly writes about key figures citing the need for an enhanced collection. “[Dr Schwartz] told ALPLF board members that securing Taper’s collection would ensure ALPLM would remain one of the most important Lincoln repositories in the world. ALPLM Executive Director Richard Norton Smith concurred with Dr Schwartz, telling the board that the acquisition would be the single most important contribution ALPLF could make for the upcoming bicentennial of Lincoln’s birth in 2009.” Following a staff shuffle, Rick Beard was hired as both ALPLM and ALPLF executive director, and from the start committed himself fully to acquisition. “Beard told the board that acquiring the Taper collection should be a ‘major priority’ because the museum currently tells Lincoln’s story without many artifacts,” Wheeler wrote.

The ensuing deal that was struck can best be described as curators on tilt.

Louise Taper built her collection of Lincolniana largely from 1985 through 2005. It is, to this day, considered among the upper echelons of Lincoln collecting. Noted Lincoln scholar Harold Holzer told the New York Times in 2008 that it was “easily the best collection of Lincoln material in private hands.” American biographer and presidential historian Doris Kearns Goodwin said “a collection of this magnitude is extremely rare . . . I know I speak for many scholars who would agree that this is a national treasure that cannot be lost.”

Taper was invited onto the board of the ALPLF in 2001 during the planning stages of the museum. She recused herself from the ALPLF vote to purchase her collection and remained on the board throughout most of the ensuing controversy, departing it in 2018.

The ALPLM’s Lincoln Collection has its genesis in 1958, when Clyde Walton, the state historian of Illinois and director of the ISHL at the time, recognized a need to collect works specifically related to the state’s prodigal adopted son Abraham Lincoln. Walton appointed James T. Hickey the first curator of the Lincoln collection.

Hickey, who passed away in 1996, is known today as one of the forefathers of Lincoln collecting, which began for him 20 years before his tenure at the ISHL. Walton’s offer to Hickey arose because of his market prowess in Lincolniana, using his connections to dealers and auctions and knowledge of where the gold is hidden to build the ISHL’s collection.

Wheeler writes, “In 1954 George Bunn, Marine Bank president, asked Hickey to go through the bank’s voluminous records and search for Lincoln items. After days of searching, Hickey discovered bank ledgers with Lincoln’s name in them. His discovery was featured in Life magazine, where he was described as a ‘farmer turned detective.’ Soon after Hickey’s discovery, Clyde Walton . . . created a new position in the library, and hired Hickey to fill it.”

Hickey was never trained as a curator. His experience in handling and researching objects was learned through building his personal collection, which he continued to build and buy for throughout his entire tenure at the ISHL, a practice that is simply not allowed by employment contract in Twenty-First Century curatorship. It is in this sense that he can be labeled a folk curator.

Only months after Hickey is made the first curator of the Lincoln collection at the ISHL, he purchases for himself the Lincoln stovepipe hat from the Tregoning Antique Shop.

Hickey remained in his post until 1985, when, in June of that year, he was forced by ISHL trustees to sign a “Conflict of Interest Statement” in which he agreed to no longer, “accept any fee or commission, or engage in the purchase, trade, or sale on his own account or any other account, of any unique or rare printed, near-printed, iconographic, or manuscript materials relating to the history of Illinois in excess of $100.”

Hickey retired five months later.

The following year, Thomas Schwartz becomes the Lincoln curator at the ISHL and is immediately held to the conflict of interest agreement. At the time, he was a graduate student at the University of Illinois.

Dr Wheeler’s report describes Schwartz’s early years there with the following: “Schwartz was quickly overwhelmed by the disorganized collection, which lacked even a basic inventory. There were items in the collection he knew very little about and could not find adequate documentation to learn more. Though Hickey was now retired and not on good terms with some members of the board of trustees, he continued to pay frequent visits to the ISHL and befriended Schwartz. His visits allowed Schwartz the opportunity to ask him about the backstory of certain items in the collection. Hickey could always recount the story behind the object and told it with enthusiasm, humor, and believability. Through these interactions, Hickey became Schwartz’s mentor.”

In other words, Schwartz was chained to Hickey because of the latter’s lack of curatorial standards and folk curatorship methods that placed the ex-curator, and not the objects, as the main repository of information about the collection.

Antiques and The Arts Weekly reached out to a number of curators and dealers in the political memorabilia field for this story; among them was Harry Rubinstein, curator emeritus at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The Smithsonian holds one of the largest collections of political memorabilia in the United States, including the top hat that Abraham Lincoln wore on the night he was assassinated.

Rubinstein said, “One of the problems that museums have is that they gain credibility by their collections. The more important things they contain, the more stature they have. So it’s common for the want to believe.”

Rubinstein went on to say that it is the curator’s professional obligation to smother that want.

“This is the curator’s business, to recognize that and take a step back and develop, do the research, locate the evidence, do the analysis, and not just say, ‘So-and-so told me it is, therefore it is.’ Every major museum in the world gets a call every day from someone who has something with a story. The role then is to do the work, to find out if it is what it is purported to be.”

Of the four hats claimed to be Lincoln’s, only two are deemed credible by the political memorabilia community.

The Smithsonian’s top hat is considered the most credible example known, collected as evidence by the War Department from the scene of Lincoln’s assassination at Ford’s Theatre in April 1865. Other relics in the Smithsonian’s collection include the cup he drank from just before he and the First Lady set off for Ford’s Theatre, the inkwell he used to draft the Emancipation Proclamation, his office suit and gold pocket watch.

From their inventory listing, “After Lincoln’s assassination, the War Department preserved his hat and other material left at Ford’s Theatre. With permission from Mary Lincoln, the department gave the hat to the Patent Office, which, in 1867, transferred it to the Smithsonian Institution. Joseph Henry, the Secretary of the Smithsonian, ordered his staff not to exhibit the hat ‘under any circumstance, and not to mention the matter to any one, on account of there being so much excitement at the time.’ It was immediately placed in a basement storage room. The American public did not see the hat again until 1893, when the Smithsonian lent it to an exhibition hosted by the Lincoln Memorial Association.”

Following that exhibition, the Smithsonian’s hat was featured in an 1896 lawsuit brought on by descendants of the Reverend Phineas D. Gurley, who claimed he was given the hat as a souvenir by Mrs Lincoln following the President’s second inauguration. According to Steven Lubar and Kathleen M. Kendrick’s Legacies: Collecting History at the Smithsonian, 2001, “Gurley’s widow claimed to have deposited the hat in the Patent Office after her husband’s death in 1865. But the Smithsonian maintained that the hat had been picked up at Ford’s Theatre by the authorities and turned over to the War Department. After an initial ruling in favor of Gurley’s family, the Smithsonian finally won the ‘Lincoln Hat Case’ on appeal, and the hat [was] quietly returned to storage in 1897.”

The second hat with plausible, but factually less stable, provenance is located at Hildene, the former summer home of Robert Todd Lincoln and his wife, Mary Harlan Lincoln, in Manchester, Vt. By lore, this hat descended in the Lincoln family to Robert Lincoln, the only child of the President to live to adulthood and have a family of his own. Robert Lincoln had three children who produced three grandchildren. It descended in the family until Robert’s grandson, Lincoln “Linc” Isham, gave the hat to Miss Amy Anne Lapham, then-owner of the Dorset Inn. The Dorset Inn is a historic lodge, still running, that began business in nearby Dorset, Vt., in 1796.

According to Hildene collections manager Catherine Sharkey, Linc was a frequent diner at the inn during this time.

The very first document that we have connecting this hat to Lincoln is a notarized letter in 1984 from Mr. Frederick Whittemore, the owner of the Dorset Inn at that time. An excerpt reads, “In 1938, I took ownership to [sic] the Dorset Inn from Miss Amy Ann Lapham. At that time the Lincoln Hat, in a decorated Hat Box, was on the Piano. Miss Lapham gave it to me as she had no children. She told me that Lincoln Isham gave it to her as he often dined at the Inn and had no family to give it to.” Whittemore returned the hat to Hildene in 1984, where six years prior the nonprofit group the Friends of Hildene won a legal battle to purchase the property and save it from development. When Hildene received the hat back, the nonprofit was in the midst of rehabilitating the property to form it into a public-facing historic house museum.

The ALPLM’s top hat needs no introduction to our readers.

We will quote Dr Wheeler on its sole piece of evidence connecting it to Lincoln: “The provenance of the stovepipe hat relied on a 1958 affidavit signed by Clara Waller of Carbondale, Illinois. In the document, Waller claimed Lincoln gave the hat to her father-in-law, William Waller, during the Civil War in Washington. When Waller died in 1891, his son Elbert Waller inherited the artifact and treasured it for the rest of his life. When Elbert died in 1956, Clara sold it to an antique store in Carterville, Illinois, where James T. Hickey, the curator of the Lincoln Collection at the Illinois State Historical Library, purchased it for his personal collection. Louise Taper purchased the artifact from Hickey in 1990, before selling it to the ALPLF in 2007.”

The final hat, which has also been discredited by the professional community, was owned by famed collector Malcolm Forbes. The collector reportedly purchased it privately in the 1980s and it came up for sale during his run of sales at Christie’s in the early 2000s. This hat’s provenance story challenged the example at the Smithsonian, as it was purported to be the hat Lincoln wore when he was assassinated. According to one dealer we interviewed for this story, “Many of us did not like that hat. We didn’t think the provenance came up to the standards we individually or collectively thought it should . . . Many of us didn’t like it in the first instance, and we certainly didn’t like it when it was reoffered in the second instance.” The hat passed at auction and has disappeared from public view since.

I will also include — for nothing more than good fun — that one of our readers pointed us to a “Lincoln stovepipe hat” offered for sale at publication time on the Lancaster, Penn., Craigslist for $2.4 million. The seller did not respond to our inquiries, but wrote in the listing that it was produced by J Y Davis and was “one of a kind and maybe the most recognizable piece of Americana” and that they had “purchased this famous, very important piece of American history 14 years ago.”

In regards to research on the Lincoln top hat in the ALPLM collection, Dr Wheeler’s report makes clear in no uncertain terms “ . . . no one at ALPLM conducted any research on the object before it was acquired in 2007.”

This factual analysis puts Dr Schwartz, who acted as the primary advisor to the ALPLF on all history-related matters, in a tough place.

In its first response to doubts about the top hat’s provenance, the ALPLF put out a release that largely placed the curatorial oversight of the purchase in the library and museum’s hands, writing, “The presidential library, its executives and historians helped the foundation evaluate and acquire the [collection].”

As Dr Schwartz failed to do any research, it became appropriate to pose the question to professionals in this field about what kind of research would have been adequate. In accordance with modern curatorial standards, what needs should be met, what boxes must be checked, in order to properly attribute a piece of political memorabilia as having been owned by someone?

We posed this question to Smithsonian curator Rubinstein; dealer of Lincoln-related artifacts and owner of Abraham Lincoln Book Shop, Inc., Daniel Weinberg; and Don Ackerman, consignment director of the historical department at Heritage Auctions and the editor-in-chief of The Rail Splitter, a journal for the Lincoln collector.

“When somebody says they have an object associated with a person or an event, first we try to see if the story makes sense,” Rubinstein said, and these first two points were reiterated by Weinberg and Ackerman. “If this was something that passed down from great-grandparents, and they lived in Idaho at the time and never left the ranch, then you can assume that it’s unlikely they ever got something from Teddy Roosevelt in New York. Second, we see if the object fits within the story line. You know George Washington never owned an electric toaster. Usually it’s not that wide, but sometimes it is. We’re talking about whether the material of the object is consistent with the period, which is fairly straightforward.”

“There’s no metrics beyond that,” he said.

If an object is deemed period correct and the story is plausible, it reaches a point when curators and sellers use their judgment, gained through their direct experience in handling related objects throughout their career.

That judgment is inclusive of a leap of faith.

Objects that are only notable for their ownership — as opposed to documents, where a writing style and methodology can be analyzed against other known works — often do not relate anything about the owner. The Lincoln top hat is clearly iconic to Lincoln, but they were also worn by hundreds of thousands of other men at the time. What about the gloves he wore? The cane he carried? Would anyone recognize these? We are speaking about objects of domestic life, and while some did recognize them in their contemporary times as having value for being associated with a famous figure, lesser items, like things that broke or served their purpose, were regularly discarded, like the junk in your junk drawer.

When objects turn up that have a plausible story, are period correct and can be found in documentation, curators begin to feel comfortable, but it rarely happens. More often there is no documentation — estate inventories, photographs of the figure with the object, any contemporary writing where the figure speaks about the object — which ultimately amounts to a lack of evidence. A lack of evidence forces curators to take a leap, which in some cases, even against their wealth of experience, can lead to error.

When it comes to documentation, the Smithsonian’s claim holds up as the most plausible. The hat was locked up in storage at the museum practically since it left Lincoln’s head. But when documentation comes in the form of Twentieth Century affidavits, doubt rightfully begins to emerge.

Ackerman said, “Many times, when you’re talking about objects that are owned by a famous person, you’re putting up with family lore, which is often not accurate, and if there is provenance, it sometimes might not go back very far. So it might belong to Lincoln, but the provenance only goes back to 1956 or 1957. You want the provenance to go back as far as possible . . . When you don’t see provenance until the Twentieth Century, that’s a problem because there’s a leap of faith involved.”

On family lore, Weinberg said, “Usually in cases of oral history, you just cannot rely on it. I’ve seen so many times where it has gone south — they just don’t know. Even though it may be true, you cannot use it.”

In November 2013, the ALPLF asked representatives from the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, Rubinstein included, and the Chicago History Museum to assess the top hat. They concluded, “The artifact’s provenance rested on Clara Waller’s 1958 affidavit, but in the absence of additional evidence, the affidavit alone was ‘insufficient to claim that the hat formerly belonged to President Abraham Lincoln.’”

Speaking with us again, Rubinstein concluded, “You don’t want to put something out there saying, ‘Many people say this is George Washington’s.’ There should be enough historical evidence on this that I believe it, and I can defend when the institution puts it up. That’s my simple solution.”

But what about lore that has passed down in the Lincoln family? This seems to be the only saving grace for the Hildene hat, whose documentation is equally scant as the ALPLM’s. The Hildene hat was left practically unattended for decades in a public inn.

When we asked Dr Schwartz, who left the ALPLM in 2011 to become the director of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum, whether family lore was sufficient provenance for political objects of ownership, he said, “I suppose it depends on the family. Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith had no direct knowledge of his great-grandfather, yet [we] base his documentation of family items on what he remembered hearing from his grandparents and mother.”

So indeed the Lincoln family lore means something to the collecting community, a point that is further cemented by noting that Hildene’s hat is generally accepted as authentic without much evidence, and with an infinite number of possibilities that it could have been swapped on any given day when it was at the Dorset Inn. That point is balanced against the fact that Hildene’s hat is the correct measurement, 7-1/8 inches, and is dated to 1856-59.

Weinberg was quick to point out the strength in Lincoln lore as well, though he added a caveat: “Mary Harlan — I would certainly take her word more than someone outside the family. So I have to give it more shrift . . . Although provenance by someone knowledgeable to the fact is not always correct either. As an example, there were two eyeglasses of Lincoln’s that came up some years ago together, along with a note from Mary Harlan. She had said they were her father-in-law’s. After I examined them, I would have said yes to one, but I think she was mistaken on the other — I think [the second pair] was perhaps her own husband’s instead. So even if you have an impeccable source, in this case the daughter-in-law of Lincoln, she could be wrong.”

The expanse of objects related to Lincoln’s life and figures associated with notable events in American history is a hazardous arena, but this is known to collectors of this material. Not all instances are malicious; some are hubris, others purely error.

Famously, the cabin that Lincoln was supposedly born in, entombed in a massive granite monument at Abraham Lincoln Birthplace National Historical Park in Hodgenville, Ky., is not the cabin that Lincoln was born in. The monument is, however, on the correct site of Lincoln’s birth. Lincoln’s one-room cabin was dismantled sometime before 1865, and Alfred Dennett bought the property and reconstructed a one-room cabin in 1894. That cabin then went on an exhibition tour alongside a cabin incorrectly attributed as the home of Jefferson Davis. Following a nationwide tour, both of the cabins were purchased by the Lincoln Farm Association, but they weren’t labeled during transit, causing the logs to mix. When the funds were put forth from more than 100,000 Americans for the massive monument designed by John Russell Pope, they were told it would house Lincoln’s cabin. When the monument opened in 1911, it was still the cabin Lincoln was born in. Only some time after was the record corrected. The “symbolic” log cabin standing inside the memorial today, as the Park Service refers to it now, is still this mix of logs from cabins that are under no circumstances considered historically important.

Similarly, dual claims for the knife that Lewis Payne (Powell) used in his attempt to assassinate Secretary of State William Seward have been made. The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens claims one in its collection, titled “Rio Grande Camp Knife (Bowie Knife) used by Lewis Powell in assassination attempt on William Seward, April 14, 1865.” That knife descended in the Robinson family until it was gifted to the Huntington in 1961. The catalog entry notes that following Payne’s trial in 1866, the War Department gave the knife to Sgt George Foster Robinson for his role in tackling and disarming Payne and preventing the murder of Seward. This knife is largely accepted by the political memorabilia community.

But another entirely different knife, also reportedly used by Payne in his Seward assassination attempt, surfaced in a 2001 exhibition at Union College in Schenectady, N.Y., the college that Seward attended.

Ackerman’s railsplitter.com site boasts 21 different stories of items that have hit the market that he has deemed fake. They include a Confederate-issued check to John Wilkes Booth; an 1860 Abraham Lincoln inaugural stovepipe beaver hat; a slew of incorrect documents; ambrotypes, daguerreotypes and tintypes; campaign broadsides and more. Many of them were sold on eBay.

Weinberg says he has taken more than 70 items off the market and keeps them in his Lincoln forgery collection.

“Everything has to be authenticated,” Weinberg said. “When it comes into the shop, I say, ‘Prove yourself.’ I don’t take it for granted that it’s good, I take for granted that it may not be . . . It just proves that everyone wants a piece of Lincoln. It’s not worth forging Millard Fillmore. Everyone wants to be a part of him, have a part of him. He still lives in that regard.”

On the selling side, both Ackerman and Weinberg, veterans in the field, require themselves to perform research before staking their reputatings on things, boiling it down to probability and due diligence.

Ackerman said, “As an auction company, when we sell things, if we think there’s a pretty strong possibility that it is what it is purported to be, we’ll go ahead and offer it, and sometimes it’s up to the bidder to decide if the documentation is sufficient.”

Weinberg boils down his judgment to a matter of percentage. He related that he has a bed from Lincoln’s Springfield home and a past director of that collection gave it an 80 percent chance of being right. “That’s good enough for me to say ‘Okay, that’s right,’” he said. Other times, Weinberg said, it doesn’t rise that high. He has for sale a cravat pin in the form of a coral hand holding a dagger, which has family lore attached to it that John Wilkes Booth gave it to a family ancestor. “I looked in every photo I could find and places he wrote, but I couldn’t find it and I can’t prove it belonged to Booth. Yet, when I look at it, who else is going to own this? A dentist? A pharmacist? A doctor? How about a thespian, a Shakespearian, like Booth. But I can’t prove it, so I don’t try to. I do percentages and I price it accordingly.”

Into this discussion you may lob in the aforementioned Malcolm Forbes top hat.

Forbes is still regarded as one of the top political collectors of the Twentieth Century and the ALPLM undoubtedly has things in its collection that were once a part of his. But that Forbes misstepped on his hat is in itself not uncommon. There is a want to believe. Collectors being private individuals with a real passion — they are almost certainly more prone to making judgment errors when compared to museum curators and committees that handle acquisitions by professional consensus. Louise Taper is not alone in this regard.

“I’ve seen it many times where even the most wealthy and highly respected collectors have been incorrect,” Weinberg said. “Everyone seems to have that in their collection somewhere. If you’re a big enough collector, you get things that may not be correct.”

Doubt plays a large role in the field — as Weinberg said: Prove yourself.

When items associated with Lincoln come up on the market, the community starts chattering. “Collectors tend to like to comment on things, denigrate or criticize and knock things down,” Ackerman said.

“I guess it’s healthy. If something is what it is, it should be able to withstand the scrutiny of skeptics.”

One of the arguments in defense of the ALPLM stovepipe hat is that consensus had emerged around it.

In presenting to the ALPLF board, Dr Schwartz called it “the only hat that is not questioned in private hands and only one of several in existence.”

When contracted by the ALPLF to confirm the value of the appraisal put on the Taper collection prior to its purchase, dealer Seth Kaller’s initial report on the top hat said, “This [Lincoln stovepipe hat] in the Taper Collection is generally accepted as the last remaining Lincoln top hat in private hands.”

The scope of Kaller’s evaluation specifically left out provenance research and authenticity. Per ALPLF request, it focused entirely on value.

Six weeks later, Kaller felt he needed to correct the record. He wrote to Dr Schwartz, asking, “Of all the hats purported to have been owned by Lincoln, why is this one of the three accepted ones? How is this different from the Forbes hat, for instance? Who is William Waller, and why and when did Lincoln give him the hat? Or is the connection through a Lincoln family member?”

Indeed, why was it one of the accepted examples?

Dr Wheeler’s report documents the actions Hickey took, going back to his acquisition of the hat from the Tregoning Antique Store in 1958, that ultimately raised the profile of the example then in his personal collection.

His first act was to get the 1958 affidavit from Clara Waller.

Then in 1975, when the Smithsonian refused to lend its Lincoln top hat to the American Freedom Train, a traveling exhibition, Hickey offered his own.

A dealer who would only speak off the record told us, “[Hickey] did not believe he could prove the hat was Lincoln’s. It became Lincoln’s hat in the ether after it was placed on board the Freedom Train. It came back at that point as Lincoln’s hat.”

In 1981, Hickey offered the stovepipe hat as the subject of a publicity stunt where Illinois secretary of state Jim Edgar used the hat to draw a winner during a partisan dispute over the drawing of new legislative districts. It was again publicized as Lincoln’s hat.

In 1988, Hickey loans the ISHL and then-Illinois state historian Dr Schwartz, the stovepipe hat for an exhibition at the National Museum of History in Taipei, Taiwan. Wheeler notes that the exhibition loan document indicates the value of the hat is $15,000 at this time.

Louise Taper acquires the hat from Hickey in 1990; it is unknown what Taper paid for it.

Shortly after, in 1993-94 and 1996-97, the hat is featured prominently in the exhibition “The Last Best Hope of Earth: Abraham Lincoln and the Promise of America,” curated by Dr Schwartz. It was billed as the largest collection of Lincoln memorabilia ever put on display at one time. The exhibition’s first installment ran at the Huntington Library and the second at the Chicago Historical Society.

To answer the question of why it was accepted, it was because it had exhibition history and noted Lincoln memorabilia authorities — Hickey, Schwartz and Taper — said it was right.

“Sometimes people cite exhibitions — that the item was exhibited at a museum,” Ackerman told us, “They’ll use that as supporting evidence to claim it’s real. I had a situation a few years ago where someone brought us a British uniform from the French and Indian Wars. It had been exhibited at the Smithsonian, the John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh and the Canadian War Museum. It was exhibited as an officer’s red coat from the 1750s. We did some research on it and it just wasn’t true. It was probably something from 1800 or 1810, and the fact that it was at three major museums could not prove that it was real. It was old, but it wasn’t what they thought it was. Just because it was exhibited at a museum does not mean it is authentic.”

It should also be argued that Hickey was a very human person who felt desire, like all collectors. He coveted the artifacts of Lincoln, and it was his job to find them and acquire them, and Dr Wheeler’s report notes that he did this on documented occasions against the interest of the ISHL.

In his role as Lincoln curator at the ISHL, Hickey stayed at Hildene for nearly an entire month in the 1970s, researching that collection with Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith. Beckwith “allowed Hickey to take whatever materials he wanted to add to the collection of the Illinois State Historical Library and also asked him to take materials for the Lincoln Museum in Fort Wayne, Indiana.”

Apart from the pieces he took for the library and museum, Hickey procured Lincoln’s eyeglasses and wallet for his own collection.

Hickey later sold these to Taper and the ALPLF purchased them in the 2005 acquisition, in effect paying a hefty premium for things the institution should have already owned.

Is it not painfully obvious at this point that perhaps the reason the ISHL’s collection did not include political artifacts was because its curator at the time was actively buying them for himself? We will quote Wheeler again when he writes, “The library had never considered three-dimensional artifacts a priority.” How plainly revealing that Hickey, the curator, sure did.

Among professionals today, none we spoke to diminished the accomplishments of James T Hickey. His hands touched an enormous amount of Lincolniana, and he was undoubtedly successful in acquiring most of that for the public.

Though because of his conflicts of interest, Hickey was a flawed curator. And it is found within these flaws the reason we are writing about the issue today. It is the genesis of the issue — it started here.

Dr Schwartz’s image of Hickey remains unhindered. He recently told us “James Hickey was the foremost Lincoln expert of his generation.”

When Hickey loaned items from his collection for the Taiwan exhibition, it was he again, from retirement, who wrote the placards on his own possessions.

When asked why he would not research any of that collection before sending it out on display, Dr Schwartz said, “Jim was the expert, right? He had the institutional memory, I did not.”

While it is clear that Dr Schwartz was hamstrung by Hickey’s knowledge and disorganization surrounding the ISHL’s collection, and indeed relied on him to supply knowledge to fill in the gaps, this is an essential part of the issue at hand: Hickey’s folk curatorship methods snowballed through yet another curator at the ISHL. Due diligence was disregarded when it came to Hickey.

Near the end of his life, Hickey was met with health issues. Anyone in the curator field knows the gig is poorly paid, today rising into the six figures only after a doctorate and sitting as the director of a major collection at a major museum. Hickey begins to sell some pieces from his collection to Taper, who is at the time in the prime of her Lincoloniana collecting career.

Dr Wheeler writes, “Taper viewed Hickey as a mentor and held his collection in high esteem. Like many of the people who interacted with Hickey, she had little reason to doubt his word when he said an item was authentic.”

That everyone viewed Hickey as an authority is unsurprising. Curators are authorities. Institutions are authorities. A Lincoln curator atop a premier Lincoln collection is one of the highest authorities in the land on that material. Scholars, curators and collectors rely on these titular roles to provide guidance — they are considered as close to absolute as it gets. Following due research, they lend their support to accept artifacts into the canon and deny others that don’t meet the standards.

Hickey, Schwartz and Taper were and are regarded as Lincoln scholars. They have curated, published work and taken a leading role in acquiring and disseminating information on Lincoln memorabilia. They are all contributors to consensus and they are all considered authorities.

Before Dr Schwartz ever arrived at the ALPLM, Hickey and Taper had already been friends and colleagues for more than a decade.

As she began buying in volume, “ . . . Taper quickly became a fixture at auctions that offered Lincoln memorabilia, often relying on Hickey’s advice on which manuscripts or objects to buy.”

Dr Schwartz carried on the tradition of ISHL Lincoln Collection curators offering authenticity and buying advice to Taper.

Dr Wheeler wrote, “Shortly after Schwartz was hired as Lincoln Curator at ISHL, he too became friends with Taper. His first interaction with her was a phone call ‘out of the blue.’ For the rest of his tenure at ISHL and ALPLM, he considered Taper a close friend. Like Hickey, Schwartz frequently gave Taper advice on which items to buy at auction.”

Whether he was ever compensated for his advice, Schwartz flatly denied it, “I never received any compensation from any of the private collectors, auction houses, public institutions and scholars that reached out to me with research queries during my 26-year tenure with the library.”

Schwartz’s familiarity with Taper’s collection was a contributor to its purchase by the ALPLF. Authorities had guided this collection since its inception and it was put together by a scholar. Schwartz assured the foundation that he was intimately familiar with it and went so far as to vouch for it.

Because Taper was an authority on Lincoln, held one of the foremost Lincolniana collections and was actively involved in the market, among other attributes, she was invited to serve on the board of the ALPLF in 2001. An avid buyer herself, she was a vocal supporter of acquiring objects related to Lincoln’s life for the museum’s collection.

While nonprofit governance and the roles therein are specific to individual organizations, board members are largely brought on to further the cause of the organization — to support it, guide it forward with proper direction and ensure its success. They are advocates. They should, in nearly all circumstances, act with the interest of the board ahead of their own.

This presents yet another conflict of interest: the ALPLF decides to put $23 million in the hands of its board member in exchange for objects of fluid value plus a donation of $2 million worth of objects so long as the museum names a gallery after her.

Taper’s relationship with the board in this situation brings up obvious questions of impropriety, but it is really in the ensuing negotiations that eyebrows raise and her role as a board member acting in the best interest of the ALPLF is obliterated.

Taper receives an appraisal from Charles Sachs, owner of the Scriptorium in Beverly Hills, who appraised the value of her collection at $25 million. She had worked for Sachs 30 years prior. But Taper — for reasons unknown — began playing hardball. She refused to show her prospective buyers the appraisal, saying they could have it only after an agreement was reached, though curators were allowed to inspect the collection and she availed herself to that end.

The ALPLF notes that Taper would only offer her collection as an all-or-nothing deal. The foundation was unable to pick what would benefit the ALPLM’s already 12-million-object-strong collection.

Why?

Why would the ALPLF’s own board member strong-arm the group through a $23 million sale by not allowing inspection of the collection’s most recent appraisal or the elimination of duplicates that would serve no benefit?

From the very beginning, other prospective buyers were used to build pressure on the ALPLF, first by Dr Schwartz. Wheeler writes, “[In September, 2005] Dr Schwartz reported to the ALPLF board of directors that Taper was willing to sell her formidable Lincoln collection. He said she wanted to see it go to ALPLM, but he acknowledged she might also sell the collection through an auction house like [Christie’s].”

A period of unrest followed at the ALPLM/F, with the executive director of both organizations Richard Norton Smith resigning in March 2006. Rick Beard was brought on as executive director in November. Negotiations had not progressed in that interim, but began to pick up pace thereafter. But in this same month, Dr Wheeler writes, “Taper sent word that a second interested party had emerged who had the funds in hand to purchase her collection outright. She told the board time was of the essence and asked them to make a decision whether to purchase by the end of the meeting.”

Dr Schwartz, Beard and others started going to bat for the collection, but major concerns were brought up by other board members that they needed to see an appraisal before spending $23 million. They spent $25,000 to hire Seth Kaller to look at the objects’ face value. He flew out to the collection and concurred the total was worth the $23 million.

Still without so much as an itemized list, the board voted unanimously to buy it.

The ALPLF still defends this position, telling us, “In 2007, the Foundation was faced with a monumental decision: take on $23 million in debt to acquire the largest collection of Lincoln artifacts (known as the Taper Collection) or watch them all quickly disappear to the auction block. With the urging and support of the State of Illinois, we made the right decision.”

Hindsight still doesn’t appear 20/20 in 2020. Perhaps the most obvious thing to do would have been to let the collection hit the block and go for wholesale prices, picking and choosing the things you would want and disregarding those that would create duplicates. Perhaps instead of getting strong-armed by its board member, the ALPLF should have balked at these backhanded negotiations.

Instead of purchasing it, the ALPLF might have listened to the numerous voices, aside from its consultant Dr Schwartz, who were urging caution, like Seth Kaller.

Weinberg told us, “I once said, and I’ll reiterate it right now, if the hat walked into my shop, I would not buy it.”

Perhaps the hat would have flopped and passed at public sale, just like the Forbes hat did.

No one is arguing that Taper was not owed the proper amount for her collection, but the manner in which the sale was pushed through was not amicable, or even-footed, to the ALPLF. That the negotiation was “all or nothing” and “buy it right now or lose it,” like Taper herself foresaw the future 2008 financial collapse that sent values plummeting, is revealing. The context of all of this taken together speaks to a board member who was not acting in the best interest of the ALPLM.

Even though she remained on the board of the foundation following the sale, a March 2016 ALPLF report notes that Taper did not cooperate with the committee at that time in its attempts to investigate any impropriety with the purchase of her collection.

How much is the ALPLM’s credibility ultimately worth?

We round back to the issue of authority, which we must conclude is the main reason the ALPLF, after 13 years, refuses to accept its victimhood.

Because in so doing, the ALPLM compromises its institutional authority. The leading institution of Lincoln scholarship would have to admit it was wrong on its most prized object — the show piece, the greatest relic of Lincolniana — and that its curators, who held the chief role on Lincoln memorabilia for 57 years to that point, were — intentionally or unintentionally — not doing the research and disregarding standard curatorial practice. With the ALPLM’s Lincoln collection now numbering to 52,000 objects, how many things does that call into question? The cost builds.

The most damaging aspect of Wheeler’s report is put forward when he wrote, “In response to the provenance issues that were raised in 2012, ALPLM did not respond like a responsible museum. Instead of conducting an honest inquiry and perhaps seizing on the opportunity to educate the public about provenance-related issues, ALPLM assumed an overly defensive position. The 2013 document, “Lincoln Stovepipe Hat: The Facts,” contains untruths and appears to have been issued solely to combat critics.”

Wheeler notes that the document was drafted by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency (then-parent agency of ALPLM), with the assistance of the curator of the Lincoln Collection, Dr James Cornelius, who replaced Dr Schwartz after his departure the year prior.

Chronologically, “The Facts” document follows a pattern of behavior that began in April, 2012, when the newly minted ALPLM Lincoln curator Dr Cornelius rewrote history on the institution’s Lincoln stovepipe hat, changing its official backstory to better fortify the hat’s provenance critiques. Wheeler writes, “In response to his inquiries, Dr James Cornelius, then-curator of ALPLM’s Lincoln collection, announced that the museum had decided on another scenario entirely. Instead of acquiring the hat during the Civil War, Dr Cornelius said Lincoln must have given Waller his hat in 1858, in Jonesboro, Illinois, during the Lincoln-Douglas debates. Dr Cornelius explained that Dr Schwartz told him about the new interpretation shortly before he resigned as state historian the previous year. ‘I guess you’d say we’ve taken something of a historic liberty in re-dating it to a much more plausible time and place,’ Dr Cornelius explained.”

Dr Cornelius was fired in 2018, the reasons withheld. According to the Herald & Review, “The agency did release a heavily redacted document dealing with Cornelius’ dismissal. The document has five entries that lay out actions that led to the firing. All of that is blacked out on the document. It concludes saying Cornelius violated work rules and rules of conduct laid out in the employee handbook for the now defunct Historic Preservation Agency, and cited ‘specific instances of unethical conduct’ that also were redacted.”

Following Dr Cornelius’ tenure, the ALPLM scrapped the position known as curator of the Lincoln Collection, rebranding it as the Lincoln historian and filling it with Dr Christian McWhirter.

Under Dr Cornelius’ tenure, it will forever be written in stone that the ALPLM released “untruths” to fortify its authority against critics who, in the context of modern curatorial standards, were and are correct.

The last bullet point on “The Facts” document used to bolster the hat was, “Noted Lincoln collectors James Hickey and Louise Taper were each confident enough in the hat’s origin to buy it in later years.”

The ALPLM used its authority as Lincoln scholars to say, “It is because we say it is,” coupling its credibility to a train destined to crash. It spun the facts to make it appear as if the curators did the research, when they hadn’t.

The actions of Dr Cornelius amount to a spin job at worst, and a disregard for curatorial practice at best. The cost builds.

In a statement from the ALPLF, chief operating officer Rene Brethorst told us that they have paid down “over $22,873,038 in principal, interest and fees — or more than 62% of the total debt since 2007.”

In December, the ALPLF released a statement noting the total true cost of the loan at that time, including interest and fees, had built to $31,699,967. That means that the true cost of the ALPLM’s stovepipe hat has risen to more than $8.2 million, but only if they paid that loan off in full right now.

The ALPLM/F would argue that research is not done, and Dr Wheeler would agree. There is more research into Waller that the historian has yet to look into. But outside of a sepia-toned photograph with Lincoln handing a hat to William Waller himself, a period image with period handwriting describing the event or at bare minimum a note where Waller writes about the hat — would you trust it now even if they did find one? — the foregone conclusion is that it cannot currently be attributed to have been owned by Lincoln, and the lack of evidence dictates that it never should have been attributed to Lincoln at any point in its past.

The total cost of the Taper purchase is rising by the day, which makes it even more curious as to why the ALPLF wouldn’t call a spade a spade, or “Lincoln’s stovepipe hat” a “Nineteenth Century stovepipe hat in the style of those worn by Lincoln” and begin to recoup the cost of the hat at $6 million. In terms of damages, that the ALPLM lost credibility is its own doing, and the fact that it took them so long to determine they don’t have Lincoln’s stovepipe hat will make for a difficult argument if they decide to pursue the costs of interest.

The cost built, nearly 25 percent of the collateral value vanished, and the loan remains. But no victim has come forward yet.

Among other functions, the ALPLF has been heavily focused in fundraising to pay off the Taper purchase in an effort to get net-positive and move forward.

It has raised the initial $22.87 million through direct asks of philanthropically minded individuals, corporations and foundations, and some limited use of its financial reserves, as well as through its signature event — the Lincoln Leadership Prize dinner. Brethorst says there have been 785 corporate, foundation and individual donors to retiring the Taper debt, what they call the Permanent Home Campaign.

When the ALPLF awarded President George W. Bush with the Lincoln Leadership Prize in 2019, it raised over $1.2 million, its highest total yet.

Individual donor campaigns that have proved fruitful include Lawyers for Lincoln, a paver campaign, underwriting artifacts, direct mailings and through naming exhibits, chairs and benches on the property.

Regardless of the media blitz in 2019 prophesizing the end of the ALPLM as it sold off the duplicates in its collection, it had already been doing so through 2016, 2017 and 2018, raising $190,000 toward the loan.

ALPLF board members have hosted fundraisers, including Doris Kearns Goodwin, whose event coinciding with the release of her book Leadership in Turbulent Times raised approximately $100,000.

Brethorst noted, “While our board has been very generous, we are going to be asking them to be even more so with their time and treasure to help pay down the debt.”

“Unlike the presidential libraries of most Twentieth and Twenty-First Century presidents,” she said, “the ALPLM receives no federal funding and has no robust seven-, eight- or nine-figure endowment. Being 15 years old, it doesn’t have generational giving whereby the tradition of contributing to the institution is passed down within families from one generation to the next. Also, unlike the libraries of modern-day presidents, its namesake is not alive and cannot walk into a room and make the case for why you should give to an institution bearing his name. It doesn’t have Lincoln descendants to continue to care for and support their [ancestor’s] legacy. But it does have Abraham Lincoln, and generous, patriotic American leaders who understand the importance of preserving our national heritage and using the power of history to inspire future generations. Our plan is to continue to appeal to and broaden our base of generous patriotic donors who value history to secure these treasured artifacts and strengthen our institution.”

The negative publicity that has barraged the ALPLM since its inception has certainly impeded fundraising efforts. And Brethorst said, “Raising money to pay down a debt (vs. underwriting a new building or exhibit) is the hardest type of fundraising to accomplish.

“To help us succeed in this effort, we are very excited to work with the newly appointed ALPLM board led by former US Secretary of Transportation and US Representative Ray LaHood as well as other newly appointed members of the ALPLM board,” Brethorst said. “This collaboration will help our stakeholders have greater confidence about our capacity to share Lincoln’s legacy with the world.”

It certainly seems that the foundation and museum are back on speaking terms following a rough patch under ALPLM executive director Alan Lowe. Wheeler notes in his report that during Lowe’s tenure, he “weaponized” the top hat against the ALPLF and created a hostile environment between the chained organizations. Lowe was ousted in 2019 after “pimping out” a copy of the Gettysburg Address to Mercury One, a temporary museum set up at the Dallas studios of conservative pundit Glenn Beck.

Amid the ALPLM and ALPLF both seeking new executive directors, a new committee has been established to decide a course of action on the stovepipe hat. It will be composed of members of the ALPLM’s new board of trustees and members of the board at the ALPLF. A decision could be coming. Should Taper offer to return the funds for the hat to the scholarly home of Lincoln? Perhaps the ALPLF could use some good faith, but will it even request it?

It is notably ironic, in a story that balances on the fulcrum of curatorship standards, that Dr Schwartz used Hickey so often for his memory, for his lore. It begs the question of how much of the ALPLM’s collection is based on Hickey’s lore? And indeed how much of it should be revisited?

In his speech at the ALPLM’s opening ceremony in 2005, Senator Barack Obama said, “We are here today to celebrate not a building but a man. . . . It serves us then to reflect whether this element of Lincoln’s character, and American character, that aspect that makes tough choices, and speaks the truth when least convenient, and acts while still admitting doubt, remains with us today. Lincoln once said character is like a tree, and reputation like its shadow. The shadow is what we think of it, the tree is the real thing.”

The tree has fallen. It’s time to plant a new one.