“Chelsea Children” by James McNeill Whistler, 1897, watercolor on paper, 5 by 8½ inches. National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Freer Collection, Gift of Charles Lang Freer. F1902.116a-c.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

WASHINGTON DC — In 1901, connoisseur-collector Charles Lang Freer described James McNeill Whistler’s intimate city scenes as “superficially, the size of your hand, but, artistically, as large as a continent.” In sympathy with the expansive spirit of Freer’s observation, Dr David Park Curry and Dr Diana Jocelyn Greenwold have organized the far-reaching “Whistler: Streetscapes, Urban Change” at the National Museum of Asian Art’s Freer Gallery of Art, part of the Smithsonian Institution. These curators invite viewers to think about Whistler’s depictions of less-fashionable areas of European cities — a topic the expatriate American explored throughout his career and via various media — as expressions suiting his artistic style and clientele. The pair also ask attendees to consider how these images and inherent ideas relate to issues currently faced by residents of stressed city districts and to the consequences, unintended as well as intended, of urban renewal and gentrification. Also key are the retailers Whistler included in his visions, particularly those offering the old, the previously owned and the recycled — the predecessors of Twenty-First Century shops selling antiques and vintage items.

The overall concept is an unusual one. Two institutions shared the same exhibition theme and co-published the catalog Curry authored, but engaged with him as guest curator to create separate exhibitions. (Maine’s Colby College Museum of Art, the other entity involved, mounted its show during the summer and early fall of 2023.) In keeping with loan restrictions stipulated by founder Charles Lang Freer, the installation at the Freer Gallery draws totally from its own collection. Greenwold, the Lunder curator of American Art at the National Museum of Asian Art and the exhibition’s in-house curator, stated that “Our iteration is a really rich opportunity for us to bring out many of our beloved, but also some of our very rarely seen, etchings and lithographs, and to showcase some beautiful pastels and watercolors and our marquee collection of Whistler oils.” She further explained that some of these works have not been on view since they were purchased by Freer. The exhibition, which launched in 2023 and runs until May 4, marks the 100th anniversary of the opening of the Freer Gallery of Art in 1923.

“Rag Shop, Milman’s Row, Chelsea” by James McNeill Whistler, 1887, etching and drypoint, ink on paper; 5-15/16 by 9 inches. National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Freer Collection, Gift of Charles Lang Freer. F1903.160.

The Washington DC display is also distinct in arrangement, architectural setting and interpretive enhancements. In regard to the last, the voices of local activists, leaders and urban planners with ties to the nearby neighborhoods of Anacostia and Capitol Hill are incorporated into the exhibition. Their reactions to select pieces are shared via the Smithsonian’s Hi mobile video guide. Greenwold observed that visitors get to see and hear “community members…talking about images that speak specifically to them and to questions of gentrification, historic preservation and maintaining a sense vitality and culture as this urban landscape changes drastically. This is an opportunity for us to map some of these concepts that were very prevalent in Whistler’s time onto our own city which is experiencing a similar type of rapid change and to think about the repercussions for us.”

James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), whom Curry calls “the first great Modernist,” referred to his street scenes as his “shop game.” He created mood-filled, lightly peopled vignettes set in London, Paris, Venice and other European cities. His glimpses of store fronts, alleyways, embankments and wharves were sometimes specific and identifiable, and sometimes not. These pictures functioned well for him compositionally and commercially, and he went so far as to insert one of them, his etching “Black Lion Wharf,” into the showpiece portrait of his mother.

There is a tension, what Curry termed “a clear disjunction,” between Whistler’s choice of old structures and streets as subject matter and his avant-garde approach. Whistler did not champion social reform or architectural preservation through his art; his slant was more evocative than documentary. Curry notes that Whistler kept “a polite distance” in part through scale, cropping and other design choices. The art historian also points to another Whistler strategy: “his constant invitation for people to look. Often figures are standing over counters or looking into shopfront windows. ‘Chelsea Children’ of 1897…is a jolly good example of what he did from the get-go. Having these little figures looking, peering, examining.”

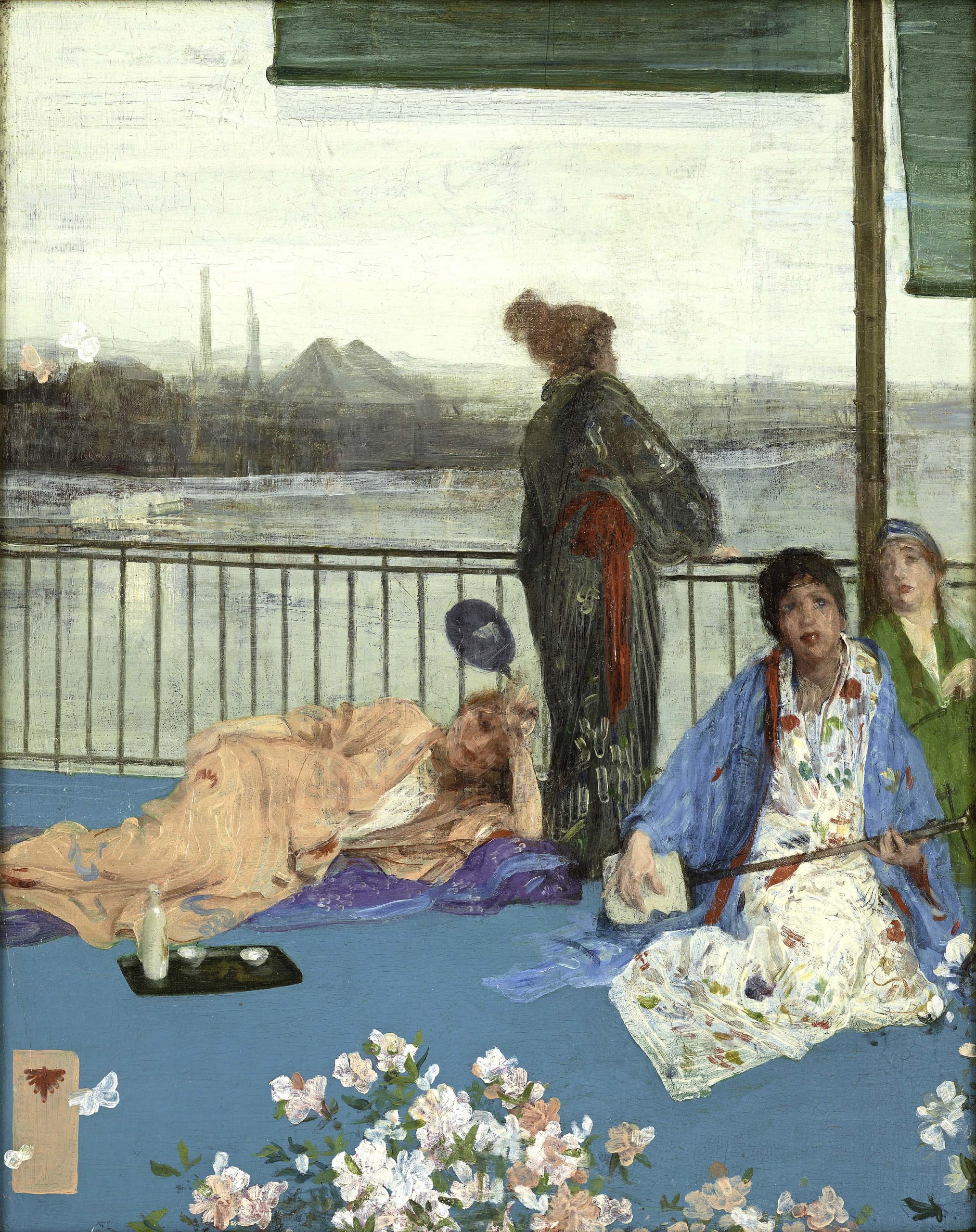

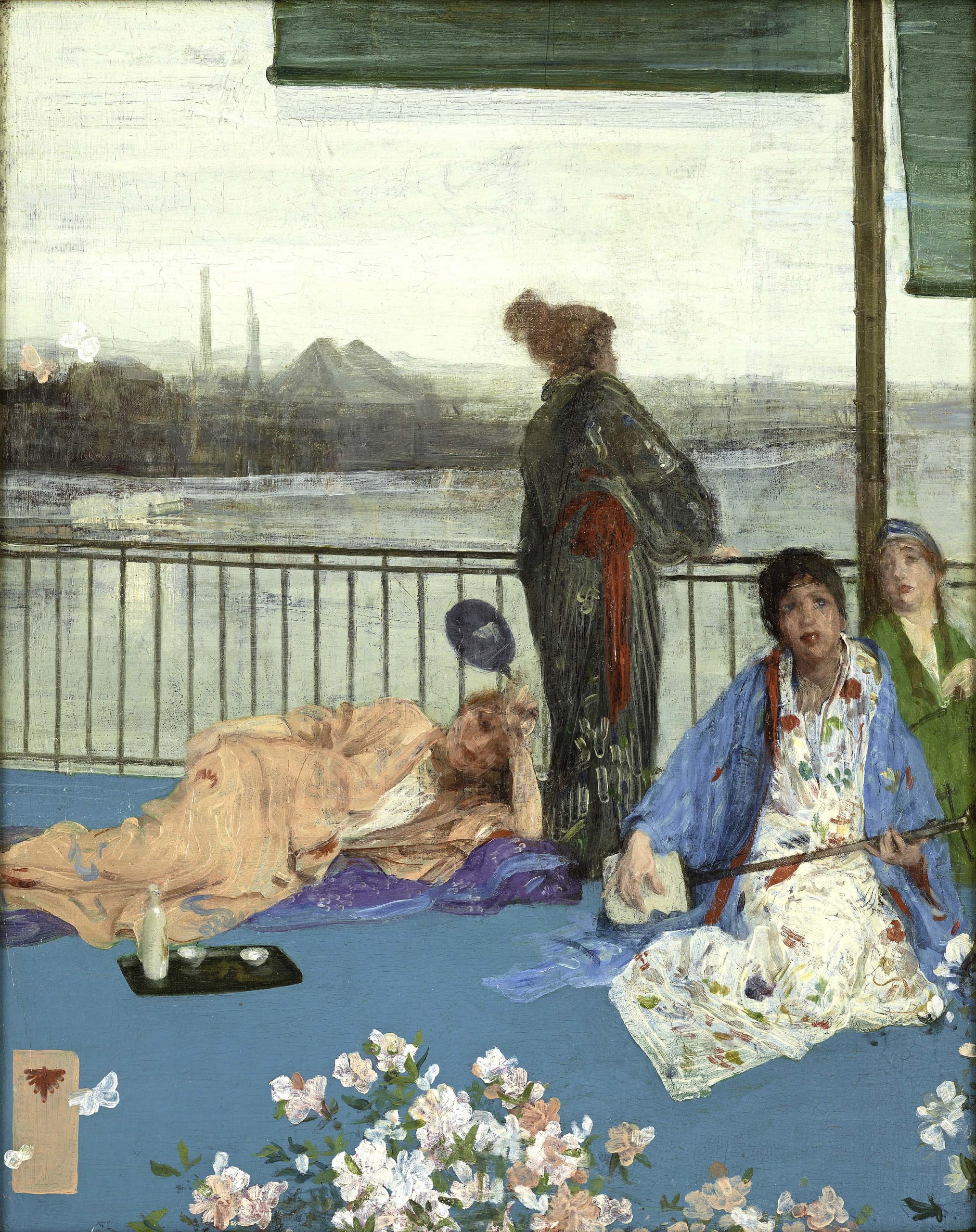

“Variations in Flesh Colour and Green – The Balcony” by James McNeill Whistler, 1873, oil on wood panel, 24-3/16 by 19-1/8 inches. National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Freer Collection, Gift of Charles Lang Freer. F1892.23a-b.

Originally from Lowell, Mass., Whistler spent a portion of his childhood in Russia and England while his father was employed as an engineer by Tsar Nicholas I. The teenager returned to the states in 1849. Six years later, he journeyed to Paris to study art and then moved to London in 1859. Using that city as a home base for the rest of his life, Whistler went on artmaking excursions to locales on the Continent and in England. His disparate influences included Rembrandt van Rijn and other Dutch Masters, English satirical artist William Hogarth and Japanese ukiyo-e artists Utagawa Hiroshige and Katsushika Hokusai.

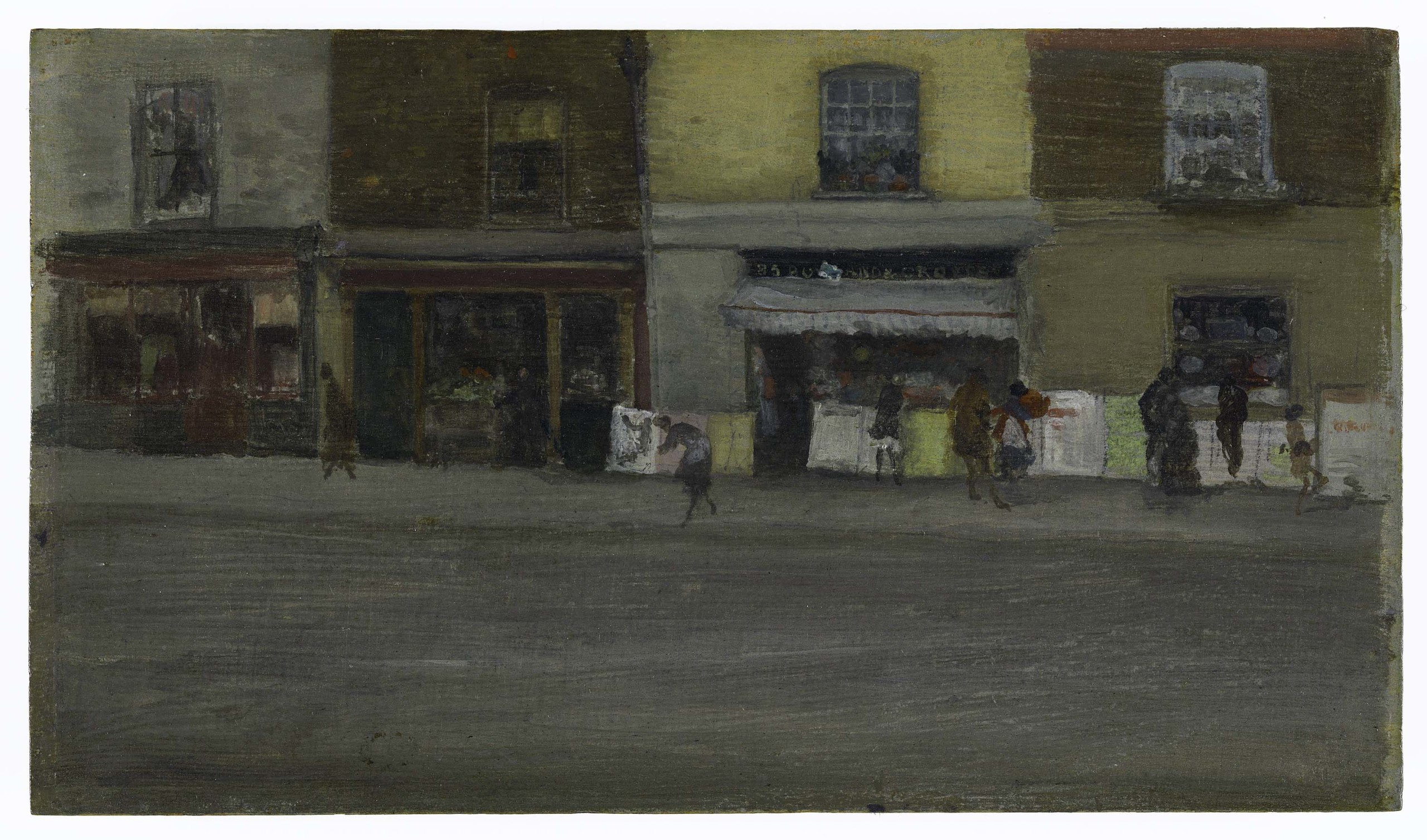

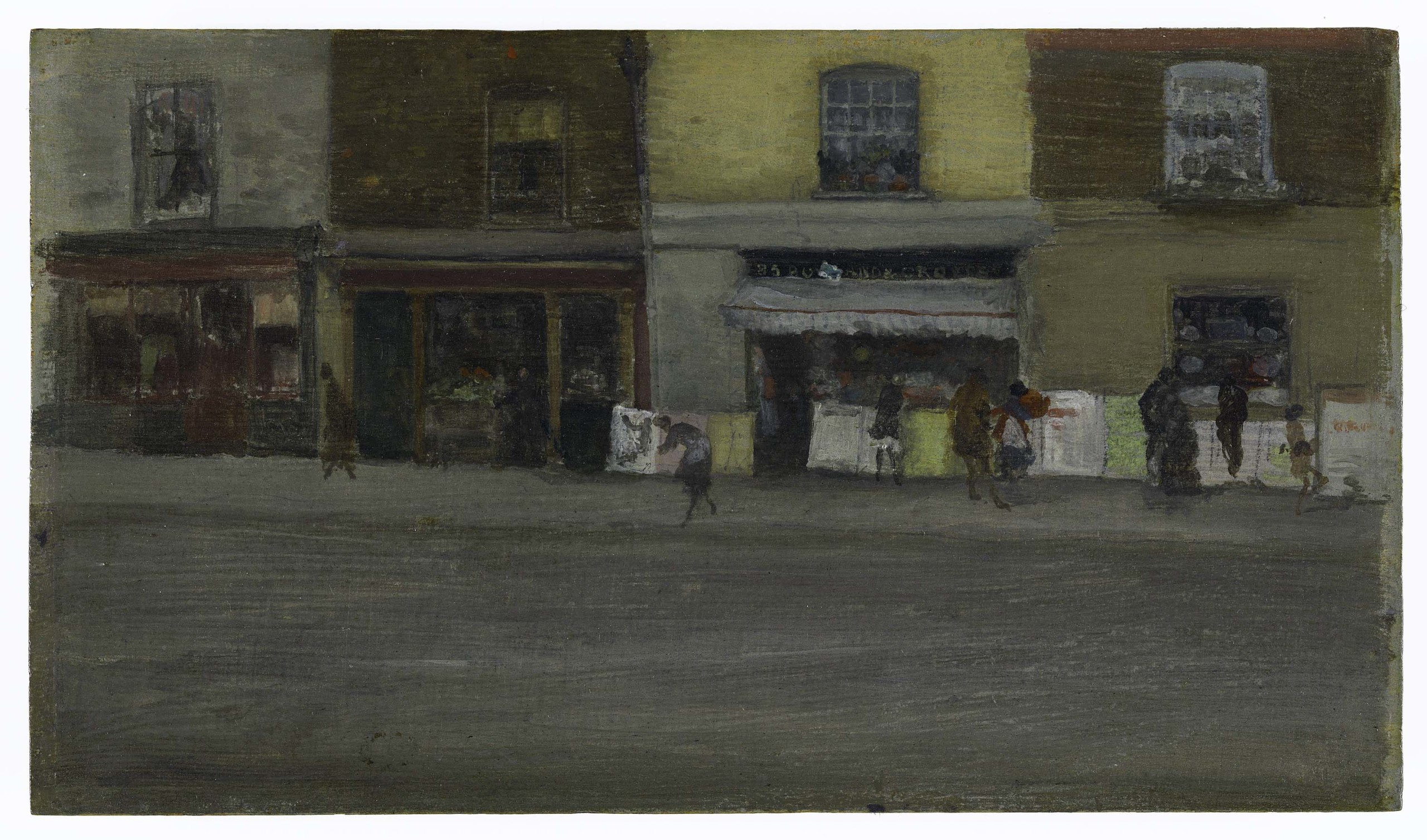

The transformation of London and Paris witnessed by Whistler is central to the exhibition. Greenwold noted that Whistler was present “during times when, in London, the wooden bridges are coming down and new steel structures are going up, moments when small-scale storefronts are giving way to large-scale department stores. In Paris, when ‘Haussmannization’ is really taking hold and decimating neighborhoods and forcing relocation of poor and working-class communities.” That term refers to Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s sweeping program of urban renewal which he oversaw from 1853 to 1870 and destroyed much of Old Paris.

“Chelsea Shops” by James McNeill Whistler, 1884, oil on wood panel, 5-5/16 by 9-3/16 inches. National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Freer Collection, Gift of Charles Lang Freer. F1902.149a-b.

Readers of Antiques and The Arts Weekly are likely interested in the linking of Whistler, his street views and Victorian-era merchandising. As described by Curry in the catalog, while the artist “seems to have especially favored rag-and-bone shops like the one in Milman’s Row, Whistler scrutinized businesses purveying all manner of other goods.” These included “butchers, bakers…, fishmongers, greengrocers…, and vendors of flowers…, nuts, sweets, melons…, wine and liquor that all attracted his eye. Whistler was also drawn to little specialty shops selling everything from used furniture…to new birdcages…, as well as those stocked with newspapers, books and prints…. He chronicled dispensaries of consumer goods ranging from cheap boots and cast-off clothing to expensive jewelry.” The older stores Whistler etched, drew and painted featured casement windows divided by mullions and muntins; their quaintness quotient rose as new department stores with their plate-glass fronts proliferated. Amid all this retail fervor, Whistler was not only an observer, but also a practitioner. For a while he ran his own store called The Blue Butterfly, a reference to his famous monogram.

While Whistler’s intent may never be fully comprehended, he was making these representations at a time when financially poor people were objectified and romanticized even as they were feared. Curry points out manifestations of this dissonance: the rich “slumming” for amusement; darkly comical vaudeville songs; all manner of prints, including the “Cries of London” street peddlers’ series; and, of course, the writings of Charles Dickens. Curry makes connections between Whistler’s penchant for portraying modest establishments and the Dickens’s novel “The Old Curiosity Shop,” the sentimental saga of angelic “Little Nell” Trent who lived with her guardian-grandfather in his low-end London antiques store until events took a tragic turn.

“An Orange Note: Sweet Shop” by James McNeill Whistler, 1886, oil on wood panel, 4-13/16 by 8-7/16 inches. National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution, Freer Collection, Gift of Charles Lang Freer. F1904.315a-c.

Perhaps Whistler’s great patron and friend, Charles Lang Freer (1854-1919), possessed even more complicated feelings about these depictions. His own story could have jumped from the pages of a Dickens novel. Born in Kingston, N.Y., Freer — whose father was a jockey, horse trainer and unsuccessful innkeeper, and whose mother died when he was 14 — had to leave school after the eighth grade to labor in a cement factory. At age 16, he was hired to clerk at a general store. There the lad’s business acumen was recognized, and mentors provided encouragement and opened doors. The highly intelligent, seemingly indefatigable Freer became a railroad car manufacturing tycoon and owner of an impressive mansion in Detroit. When Freer retired from industrial pursuits in 1899, he devoted himself to studying and collecting art, an activity he had begun earlier. He purchased his first works by Whistler, a second set of Venice etchings, from Knoedler Gallery in 1887.

It is useful to understand the multiple contexts of Whistler’s urban views. While these works hardly seem provocative to us, many of his contemporaries found them boundary-pushing and mystifying. In an unexpected twist, curators Curry and Greenwold leverage rarefied, Nineteenth Century European street scenes to promote conversation about marginalized city dwellers and their surroundings in America today. “Whistler: Streetscapes, Urban Change” is a superlative exhibition not to be missed.

The accompanying catalog with text by David Park Curry was co-published by Colby College Museum of Art; the Freer Gallery of Art, National Museum of Asian Art, Smithsonian Institution; and DelMonico Books in 2023.

“Whistler: Streetscapes, Urban Change,” on view to May 4, is at the National Museum of Asian Art’s Freer Gallery of Art at 1050 Independence Avenue. For information, 202-633-1000 or www.asia.si.edu.