In 1891, Chase established a studio in Shinnecock, Long Island, N.Y., and founded a summer art school there. This scene of his family poring over a portfolio of Japanese prints shows how work and play intertwined for the artist. “Hall at Shinnecock,” 1892. Pastel on canvas. Terra Foundation for American Art, Daniel J. Terra Collection.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

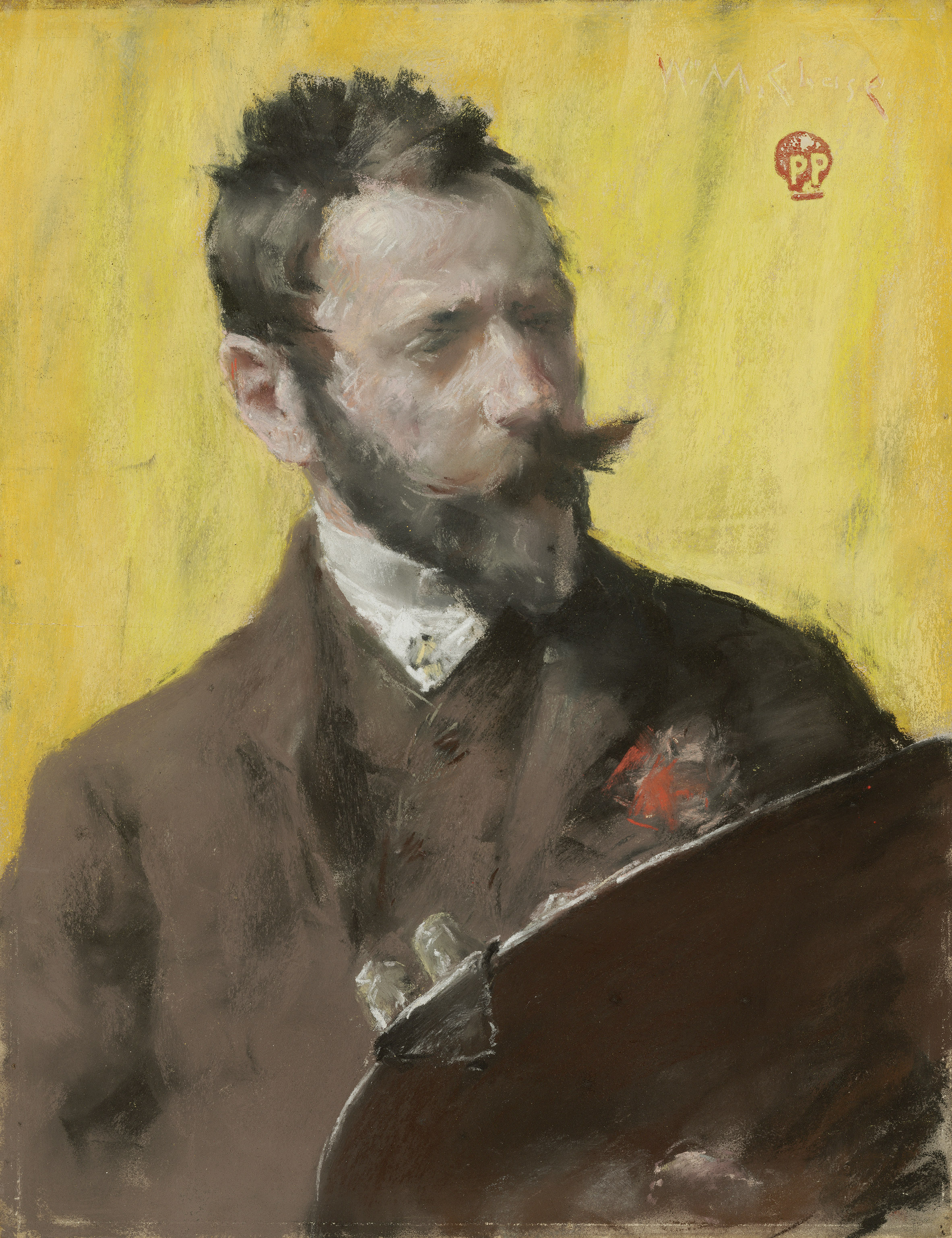

BOSTON, MASS. — William Merritt Chase is remembered today not only as one of the great artists of his generation, but also as a gifted and engaging teacher, inspiring a generation of artists who would go on to establish America as an epicenter of Modernism in the Twentieth Century. As such, he is an essential bridge between that Modern era and the time when American art was still in its infancy. His career also encompasses a time of great change in American culture, best seen in his elegantly rendered, intellectually challenging and attention-getting portraits of women. Such portraits are a highlight of “William Merritt Chase,” organized by the Phillips Collection, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia and the Terra Foundation for American Art, and on view at the MFA through January 16.

In Edith Wharton’s 1905 novel The House of Mirth, published while Chase was in the autumn of his career, a pivotal scene has the heroine, Lily Bart, participating in a tableau vivant. The term refers to a popular pastime of the turn of the century, in which participants posed in elaborate costumes and settings as living recreations of famous works of art. Lily, whose social standing is in jeopardy but whose beauty remains unrivaled, recreates a portrait by Joshua Reynolds, and Wharton’s elegant prose draws the reader into unguarded admiration. The scene is swathed in poetry and romance until its denouement, when Wharton’s omniscient narrator reveals the ugly way in which certain men in the audience have chosen to view her performance.

William Merritt Chase was also fond of tableaux vivants. In “Old Masters Meet New Women,” her insightful essay for the exhibition catalog, MFA curator Erica E. Hirshler writes that Chase used his studios in New York City and Long Island, N.Y., to stage recreations of paintings by the Old Masters he revered. As a rule, he did not literally depict such entertainments in his paintings and pastels, but a sense of theatricality is nevertheless strong throughout his body of work. His famed 10th Street Studio in New York City was a particularly theatrical place, a frequent setting for his painted portraits and interiors. Diane Paulus of the American Repertory Theater, who provides commentary for the MFA’s mobile guide, notes that Chase’s interiors are arranged like stage sets in order to highlight particular passages or moments of action.

With its striking color contrasts, this has become one of Chase’s most memorable paintings, “Portrait of Dora Wheeler,” 1882–83. Oil on canvas. Cleveland Museum of Art.

Chase’s portraits of women are also theatrical. His luminous technique and artful brushwork demand admiration, in much the same way as Wharton’s words. And yet Chase’s women are more than just stage pieces or objects of desire. In fact, Hirshler says that one of the things that distinguishes Chase’s work from that of his contemporaries is “how engaged and active his women sitters are.”

Stated another way, Chase did not paint the Lily Barts of the world. Instead, his sitters are, with few exceptions, self-possessed and in control of their surroundings in a way that was notable for the time.

In a portrait dating to 1882–83, Dora Wheeler, for example, with her steady, appraising gaze and relaxed but alert pose, is no metaphor for the vase of flowers that blends into the background behind her. Wheeler exemplified the so-called “New Woman,” a term that emerged in the late Nineteenth Century to describe a particular kind of (usually American) woman who was “not at all content to be cocooned at home,” in Hirshler’s words.

Wheeler went on to become an acclaimed artist in her own right, as well as a businesswoman, but in the early 1880s she was an art student, one of Chase’s first. Throughout his career, Chase had many female students at the Art Students League and at the school he founded at Shinnecock, N.Y., among other places. He trained them no differently from his male students. “Genius has no sex,” he wrote.

In fact, Hirshler traces her interest in Chase through another student, Lilian Wescott Hale, who was the subject of her dissertation some 25 years ago. “He treated them as professionals,” Hirshler said recently of Chase’s female students, “and gave them the confidence to pursue a professional career, which wasn’t necessarily a given at the time.”

Chase’s gifts as a teacher are reflected in a quote from perhaps his most famous student, Georgia O’Keeffe, who remembered that he “encouraged individuality and a sense of style and freedom to his students…. There was something fresh and energetic and fierce and exciting about him that made him fun.” Hirshler sees O’Keeffe’s words as confirmation of his talent as a teacher. “I truly think that one of the marks of a great teacher is that he doesn’t make his students follow and become himself,” she says, “that he gives them the tools and confidence to make their own mark.”

Chase’s gifts as a teacher are reflected in a quote from perhaps his most famous student, Georgia O’Keeffe, who remembered that he “encouraged individuality and a sense of style and freedom to his students…. There was something fresh and energetic and fierce and exciting about him that made him fun.” Hirshler sees O’Keeffe’s words as confirmation of his talent as a teacher. “I truly think that one of the marks of a great teacher is that he doesn’t make his students follow and become himself,” she says, “that he gives them the tools and confidence to make their own mark.”

Teaching, too, was an avenue for Chase’s innate theatricality. In her catalog essay, “The Performative Teaching of William Merritt Chase,” Terra Foundation for American Art curator Katherine M. Bourguignon describes how demonstrations were a fundamental part of Chase’s teaching style. As students watched, he would create a painting using the techniques he espoused, dashing off masterful studio pieces in the space of a single classroom session.

Such demonstrations were also sometimes conducted in his 10th Street studio, either for a select group of students or an invited public audience. The resulting painting was often sold or raffled off as an incentive for attending one of his lectures or classes. Others he kept, placing them in ornate antique frames that he collected and ultimately offering them to museums.

Chase established his studio, the setting for many of his portraits and interiors, in New York’s famed Tenth Street Studio Building in 1878, just after returning from Europe. “Studio Interior,” about 1882. Oil on canvas. Brooklyn Museum.

A frequent subject of such demonstration pictures was, of all things, fish from a local market. In the exhibition’s mobile guide, Boston-area chef Jody Adams identifies the species of the fish in various paintings and observes how fresh they are. Part of Chase’s shtick was that he could complete the painting and return the fish to market before it had gone bad. Such quasi-vaudevillian antics, however, should not suggest that the resulting paintings were anything less than the work of a master. An untitled fish still life in the collection of the Art Students League, for example — illustrated in the catalog although not part of the show — is a tour-de-force of early Modernism. The sweeping brushwork effortlessly articulates a series of perfectly placed ovals, from the dishes to the fish’s gaping mouth, rendered in a masterful palette of deathly gray and blood red.

Chase’s taste for pageantry also found expression in his many paintings that feature East Asian textiles and decorative arts. Works like “Spring Flowers (Peonies),” a pastel from 1889, illustrate not only the kinds of objects that he collected and that filled his studios — the fan, the vase — but also the influence of Asian art and design on his own compositions.

The section of the exhibition that is dedicated to works in this vein offered another opportunity for collaboration, this time with Hirshler’s colleagues in the MFA’s Arts of Asia department. They were helpful “in terms of teaching me what I was seeing in Chase’s pictures,” Hirshler says, as well as lending an album of Japanese prints, similar to the one that Chase’s daughters leaf through in “Hall at Shinnecock,” 1892, for display in the exhibition.

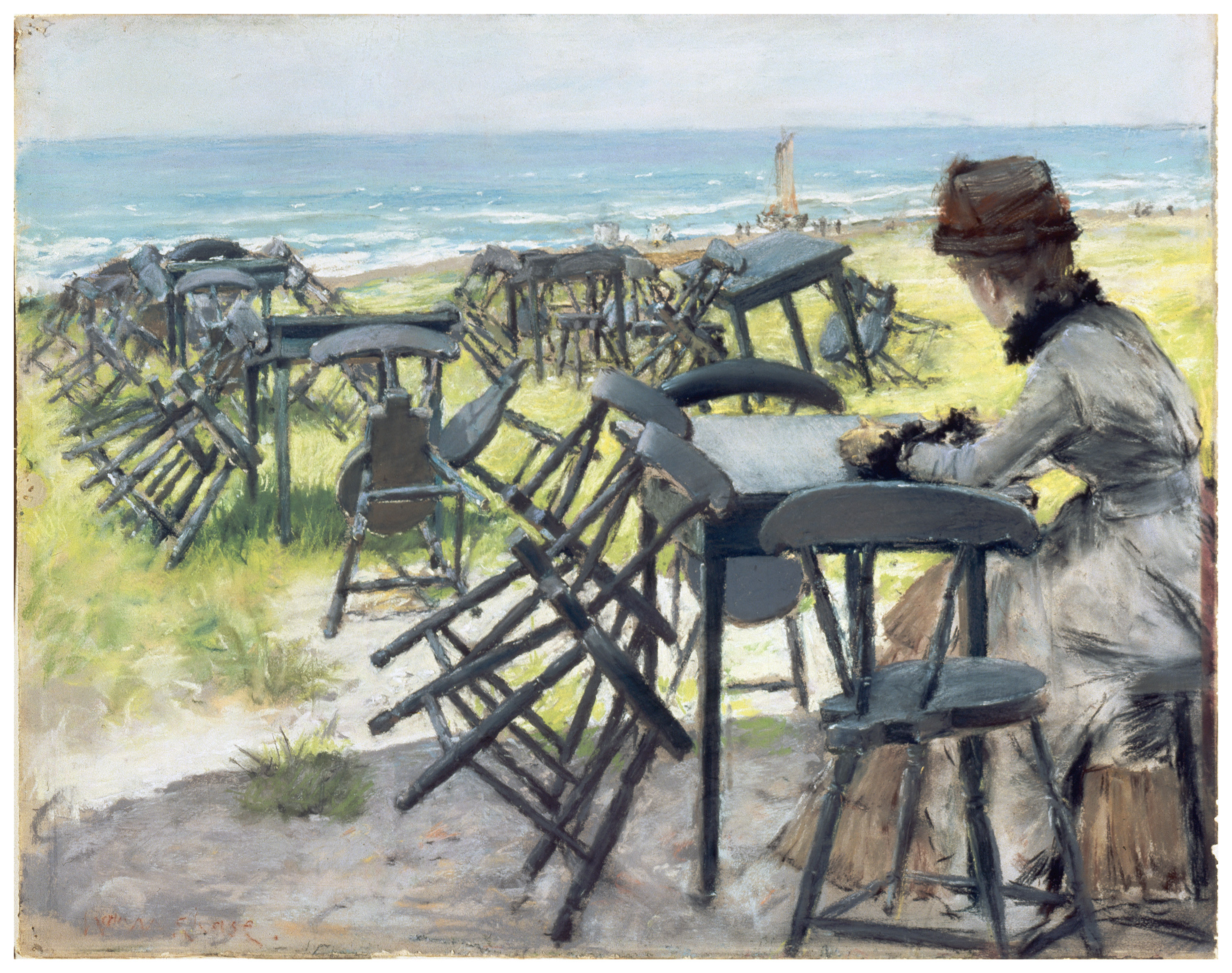

Such interiors with children at play are among Chase’s most defining works. And yet so are his marvelous self-portraits, which he created throughout his career, and his evocative garden and beach scenes, so clearly influenced by French Impressionism. So, too, are the portraits, like “Dora Wheeler” or “Lydia Field Emmet,” 1892, and the fan-favorite fish paintings.

“One of the things about Chase that makes him difficult to wrap your mind around is that he was a very eclectic artist,” Hirshler says. As opposed to artists like John Singer Sargent or James McNeill Whistler, for whom single works stand out as universally iconic, “people have different touchstone works” for Chase.

In the end, it is perhaps that eclecticism, more than anything else, that places Chase at the vanguard of Modernism, where the exhibition’s curators situate him. His interest in such widely varying subjects was, to a great extent, purely visual — a hallmark of Modernism — and he was able to spark and record that visual excitement with his easel in front of almost anything. He was also able to communicate that spark beyond the two dimensions of his paintings themselves. Many of those he taught would go on to adopt pure color and form as the primary language of artmaking.

In the late 1880s, Chase and his young family briefly lived with his in-laws in Brooklyn. Chase was fascinated with the city’s impressive parks, as well as its humble backyard gardens, which he rendered in spatially sophisticated compositions. “The Open Air Breakfast,” about 1888. Oil on canvas. Toledo Museum of Art.

“Performative” though Chase’s career may have been, it was never a performance per se. His enviable imitative powers and the sheer pleasure of his presentation may be what draw us in, but it is the power and authenticity of his vision that demand our lasting attention and respect.

“William Merritt Chase” is accompanied by two publications, a softcover “compact introduction” to Chase’s work by Hirshler, published by MFA Publications, and a full-scale, cloth-bound exhibition catalog with essays by Hirshler and her co-curators Bourguignon, Elsa Smithgall and Giovanna Ginex, as well as John Davis, with a foreword by D. Frederick Baker, published by the Phillips Collection in association with Yale University Press.

The exhibition opened at the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. Following its close in Boston, it travels to the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia in Venice, Italy, from February 10 to May 28.

The Museum of Fine Arts is at 465 Huntington Avenue in Boston. For general information, www.mfa.org or 617-267-9300.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is a writer, editor and independent art historian based in South Portland, Maine.