Bodice of Elizabeth Mance concert dress by Ann Lowe, 1960s. Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library photo.

By Laura Layfer

WINTERTHUR, DEL. — On September 9, “Ann Lowe: American Couturier,” opens at Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library, with 40 gowns in the first exhibition dedicated solely to the late designer. The debut at an institution renowned for American decorative arts, material culture, history and horticulture, proves a fitting venue in many surprising ways. Both Winterthur’s founder, Henry Francis du Pont (1888-1969), and Ann Lowe (1898-1981), contributed to the style and grace synonymous with Jacqueline Kennedy and her journey both to and through the White House. In 1961, du Pont was appointed by the First Lady as an advisor on the restoration of the White House interiors. The position helped elevate Winterthur, formerly the du Pont family estate, its collections and its programs. In 1953, Lowe was selected to create the wedding dress for Jacqueline Bouvier for her wedding to Senator John F. Kennedy. Following the nuptials, the press was eager for details on the custom gown, but Lowe was not credited by name until much later in her career. Today, she is celebrated for her talents and her tenacity. As a young Black female from the rural South, she made her way to New York City, established her own high-profile clientele, a business and a legacy that is now being formally acknowledged for its impact on fashion history.

Lowe grew up in Alabama, the daughter and granddaughter of seamstresses, and early on, the skills of the family trade were passed on. “We know that she was patterning her own clothes and sewing at a very high level from age 8 or 10,” points out Elizabeth Way, associate curator at the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology and guest curator for the show. The generational influence of Lowe’s upbringing gave her a head start in technique as well as in understanding the demands of patrons.

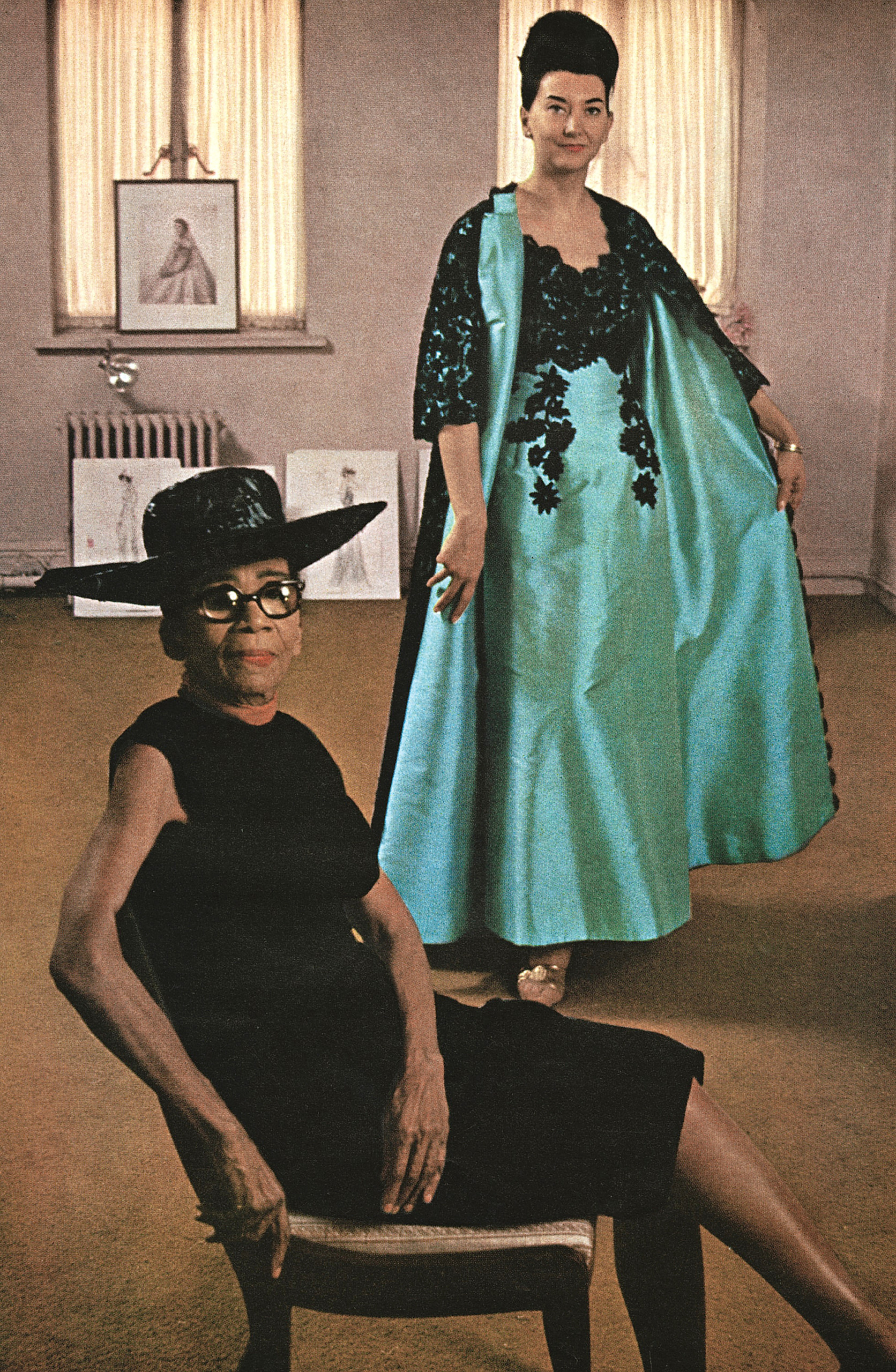

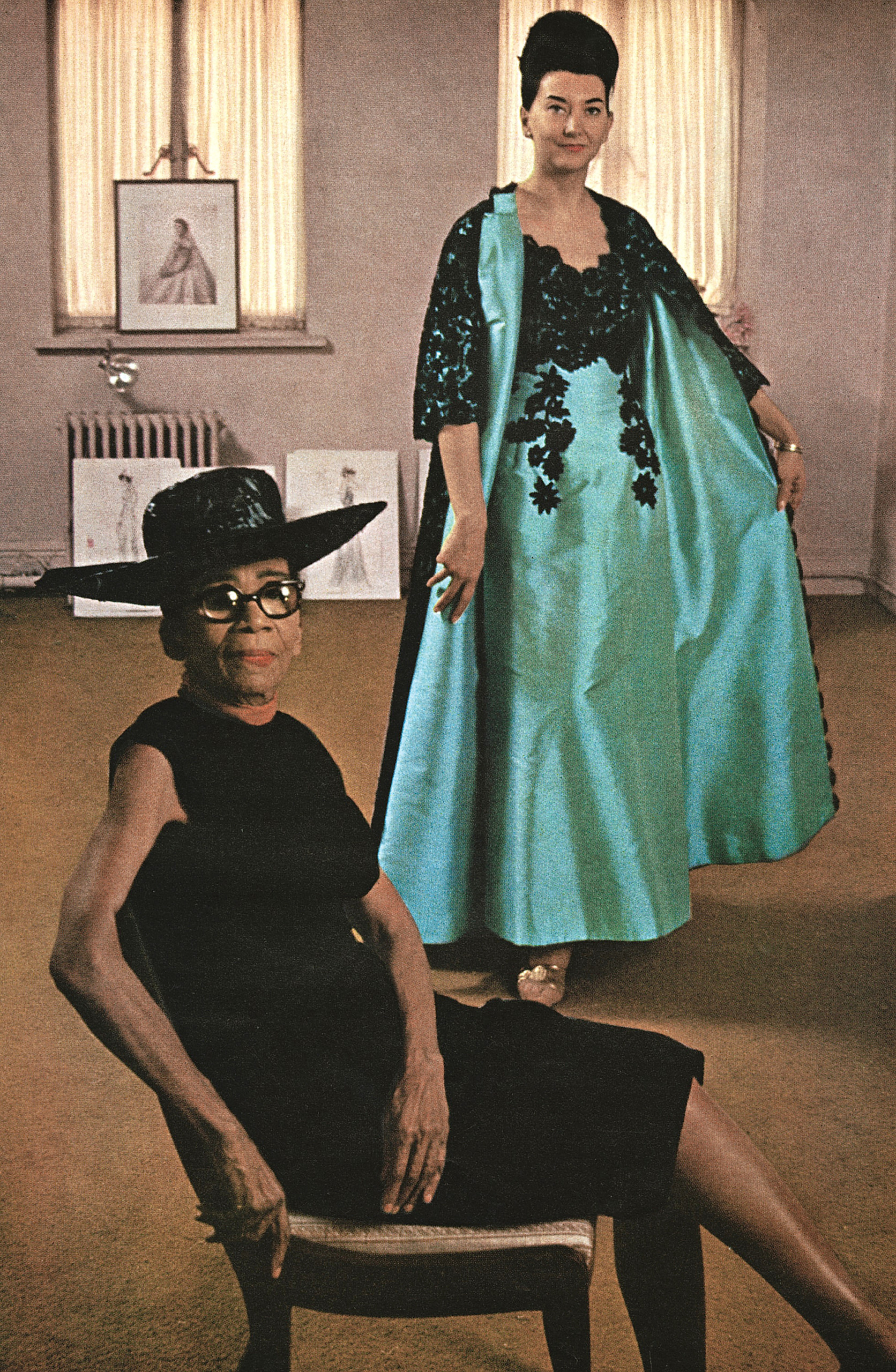

December 1966 edition of Ebony magazine. Johnson Publishing Company Archive. Courtesy Ford Foundation, J. Paul Getty Trust, John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and Smithsonian Institution. Pictured with this ensemble that blends Lowe’s style with the simpler A-line of the 1960s. Judith Guile, who worked with Lowe, modeled it.

In 1914, when her mother died and commissions for an upcoming Governor’s Ball in town loomed, Lowe stepped in and completed the orders. Shortly after, a wealthy white family with four daughters asked Lowe to be their personal dressmaker in Tampa, Fla. By then, Lowe had a young son, and with him in tow, she set out on the adventure that would alter her professional journey. She took customers on the side, and, without any formal publicity, the Lowe name became a known local entity. After saving up enough money, and with the encouragement and support of her employers, in 1917, Lowe left for fashion school in Manhattan.

The adversity that she encountered did not sway her path to success. For example, the director of the program questioned whether Lowe had the funding for enrollment and segregates her from the other classmates to work in a solitary setting. Lowe remained focused but within six months, the training was cut short anyway. That same director, who now brought students in to learn from Lowe, declared the quality of her work far superior to their curriculum. Back in Tampa, she opened a namesake storefront, took on various apprentices and became lauded primarily for her niche in bridal attire.

By 1928, a return East is inevitable in both mind and matter. “She always had her sights on New York, and it is a great transition in her career,” says Way, “it’s a place that forges many alliances.” Before opening a Madison Avenue salon, Lowe visited shops in the area asking for a seat in their workrooms in exchange for pay only if her designs should sell in their storefront. Her style may have been traditional, but the production output is always on trend. In 1964, The Saturday Evening Post calls Lowe “Society’s Best-Kept Secret.” In the know are socialites, movie stars (actress Olivia de Havilland accepted an Oscar in a Lowe ensemble), and even department stores added their own private label to Lowe’s design, a common practice of the period.

Wedding dress by Ann Lowe for Saks Fifth Avenue, early 1960s. Courtesy of Adnan Ege Kutay Collection. Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library photo.

“To this day, there remains some criticism of Lowe from members of the Black community because she, by her own admission, chose to work almost exclusively for elite white families. Later in her career, she did create gowns for members of the Black community, but that work was much more limited,” remarks Alexandra Deutsch, John L. and Marjorie P. McGraw director of Collections. Like the designs Lowe envisioned, she had a sense of the fashion forward and how to achieve it. Yet, in the decades that follow there are several ups and down. Her eyesight began to fail, making embroidery and floral appliqué, a signature Lowe detail, increasingly difficult. There were financial troubles, too, and particularly after the death of her son, the bookkeeper for the business. The most documented of dilemmas was when a pipe burst that flooded Lowe’s atelier two weeks before the Kennedy wedding and the silk-taffeta gown was completely ruined. Lowe used her money to replace the fabric, hired helpers, and delivered once again without any disruption to her patrons. It is rumored that decades later when debt threatens a closure for Lowe’s shop, the anonymous payment that came to her aid was purportedly from Mrs Kennedy.

The original bridal dress, extremely delicate and rarely on view given its fragility, belongs to the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Katya Roelse, University of Delaware Fashion and Apparel Studies professor, spent three days examining the gown in order to recreate an example, along with her student apprentices, for this exhibition. “You could really see what a tour de force this was for Lowe” says Roelse. She shares that upon close inspection one can see how the hand-sewn elements that would be visible were done with strict precision as opposed to those hidden threads where, in the haste of the situation, Lowe was understandably quicker with her needle. “Her process was not working with patterns, she cut shapes immediately out of fabric.” Following its display at Winterthur, the replica will be given to the JFK Library.

Winterthur Museum Reproduction of Jacqueline Kennedy’s wedding dress by Katya Roelse, 2022. Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library photo.

“People don’t think of us for fashion, but Winterthur supported the research and the necessary conservation that has enabled us to trace the trajectory of Lowe’s mark on design history,” points out Kim Collison, curator of Exhibitions at Winterthur. In the galleries, mannequins were manufactured with the assistance of University of Delaware MakerGym and Winterthur’s textile conservation lab. A separate room features a small show that talks about the process of designing and fabricating the Ethafoam mannequins, as well as the preparation and dressing to properly support the garments for the length of time that they are on view. The last gallery closes with a focus on contemporary designers, including B Michael and Tracy Reese, with pieces that exemplify the modern-day influence Lowe continues to have on the community of Black fashion designers and the industry in general. These pieces range from daywear to a wedding gown and include two ensembles worn to the Metropolitan Museum of Art Gala — one designed by B Michael and worn by Dawn Davis and embroidered with Lowe’s name among those of other Black designers (2021) and one dress designed by Kimberly Goldson with a cape by Dapper Dan and worn by Bevy Smith (2019).

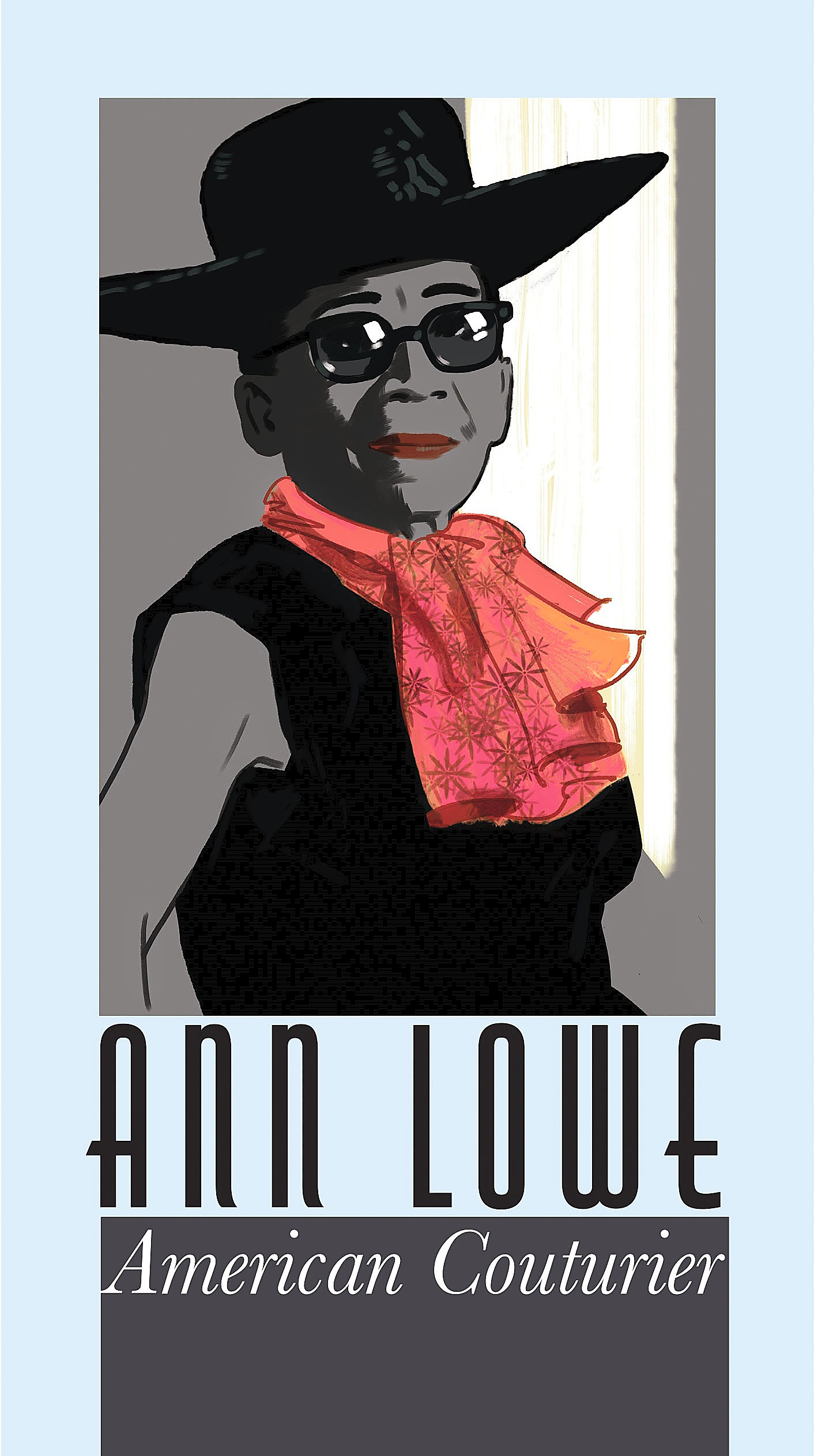

There is an image of Lowe with a chic black hat, slightly tilted, wearing dark-framed eyeglasses, and red lipstick and painted nails. It accompanies in either photograph or sketch format almost all of the marketing materials and the exhibition catalog cover of the same title (published by Rizzoli). “This was an 11th hour idea,” laughs Deutsch, “I just felt like something was missing because even in the 60s when you hear the Michael Douglas Show interview with Lowe, I found it fascinating that they really don’t talk about her — she’s almost invisible and there was something to me that said she needed to be at the forefront rather than the dresses in front of her.”

© 2023 Sally Wern Comport after Ebony magazine photograph.

The initial idea for the Lowe exhibition came from a collaborative effort of colleagues. “The word ‘inspire’ is part of our founding mission statement, and that’s how I see the coming-together of this show,” says Deutsch. “It’s about great American craft and it’s about mentorship.” When the late Margaret Powell was a cataloger on Winterthur’s staff, she had already written a master’s thesis on Lowe. The encouragement she received from Winterthur staff to continue her research now culminates in a full circle tribute to the efforts of many strong women, most notably Powell, the scholar, and Lowe, the subject.

“Anne Lowe: American Couturier” runs from September 9 to January 7. A symposium titled “In the Legacy of Ann Lowe: Contemporary American Fashion,” will take place October 20-21.

Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library are at 5105 Kennett Pike. For information, 800-448-3883 or www.winterthur.org.