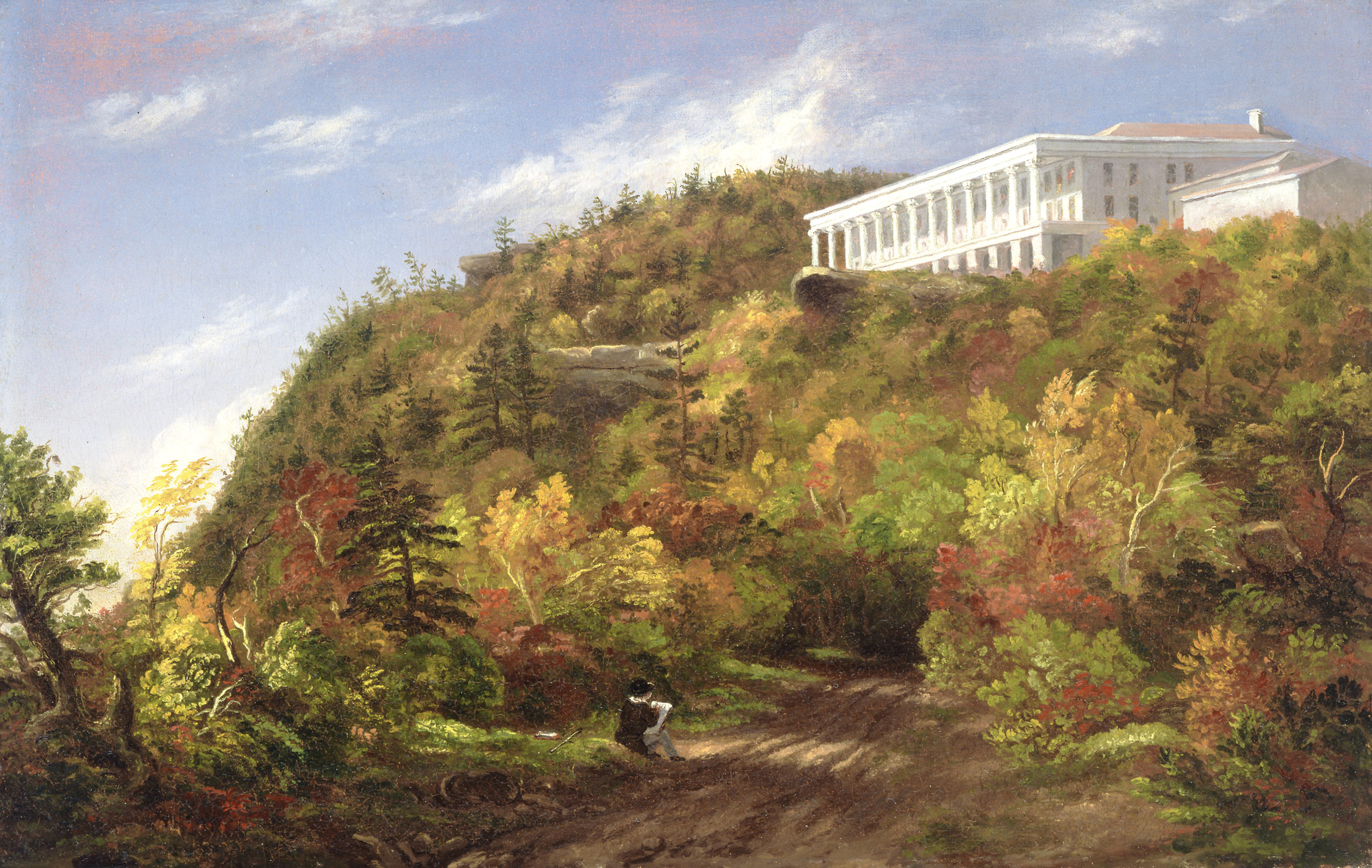

“Mountain Lake in Autumn” by Susie Barstow, 1873, oil on canvas, 20 by 30 inches, Private Collection, Photograph: Hawthorne Fine Art, New York City.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

CATSKILL, N.Y. & NEW BRITAIN, CONN. — Consciously or not, when we think of the so-called Hudson River School — the Nineteenth Century painters who created majestic American landscape views — we think of an essentially male phenomenon. Indeed, the Thomas Cole National Historic Site is more or less grounded in the concept of Cole as the “founding father” of the movement, taken up by (male) students and acolytes like Frederic Edwin Church and others after Cole’s premature death in 1848. This hierarchical leader-follower framing, however, effectively leaves out other participants, including what scholar Nancy Siegel has described as some of the “founding mothers” of the American landscape tradition. The two-part exhibition, “Women Reframe American Landscape: Susie Barstow & Her Circle / Contemporary Practices,” offers a broader vantage point. It is on view at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site through October 29, when it will then travel to the New Britain Museum of American Art November 16 through March 31.

A touchstone for the exhibition, as Siegel and her co-curators Kate Menconeri and Amanda Malmstrom acknowledge in the exhibition’s accompanying catalog, is Linda Nochlin’s influential essay from 1971, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” It’s a layered question, one that is at least partially complicated by how we define “great,” a label often applied after an artist’s death, when their career has fully played out (though Cole, to be fair, was recognized as great in his own lifetime). Since Nochlin’s essay, much feminist art history has involved demonstrating that there were, in fact, professional women artists who were recognized and acclaimed in their time but whom, for a variety of reasons, art history has failed to canonize. A central argument of the present show is that Susie Barstow (1836-1923) was one of those artists — and, importantly, that she does not stand alone, then or now, as a solitary genius but as part of a broad community of women artists participating in what we now term the Hudson River School.

“Portrait of Susie M. Barstow,” Rawson 255 & 257 Fulton Street, Brooklyn, circa 1870, tintype, 5½ by 4 inches. Private Collection, Photograph: Dennis DeHart.

The publicity for the exhibition, echoed by Siegel in a recent gallery tour, has hailed it as the “first solo show ever of a Nineteenth Century woman landscape painter,” which is a bit unfair to one of Barstow’s contemporaries, Fidelia Bridges (1834-1923), currently the subject of a solo show at the Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wausau, Wis. But Bridges is given her due here, to be sure, with an oil, “Small Bird with Flowering Ironwood,” and a small watercolor of barn swallows. Representative works are also on view by Julie Hart Beers, Charlotte Buell Coman, Eliza Pratt Greatorex, Mary Josephine Walters and Laura Woodward, many of whom were also featured in a 2010 exhibition at the Cole House, also curated by Siegel, called “Remember the Ladies: Women of the Hudson River School,” for which “Women Reframe American Landscape” was conceived as a kind of sequel. “To have this opportunity to focus on one particular artist and really give her a retrospective that she’s never had is the next important step in terms of curating,” says Siegel.

That earlier show furnished something of a revelation that so many women were participants in this defining American landscape tradition, particularly given the obstacles they had to overcome. In this pre-suffrage, pre-women’s rights era, women faced significant legal limitations, including their ability to govern their finances, own property and run businesses, coupled with the obligations of childbearing and family life that, with rare exceptions, were exclusive to women. Perhaps it is not surprising, then, that many of the women to succeed as landscape painters (which necessarily involved large periods of time outside the home) were thus unencumbered. Neither Barstow nor Bridges ever married and instead developed a network of female friends, traveling companions and “partners” (the term is left for readers and viewers to interpret as they will). Such arrangements enabled them to travel in pairs or groups rather than alone or with a male companion — which would have been unthinkable — and fostered networks of influence and knowledge sharing that were somewhat independent of the more formal teacher-student relationships from which they were largely excluded.

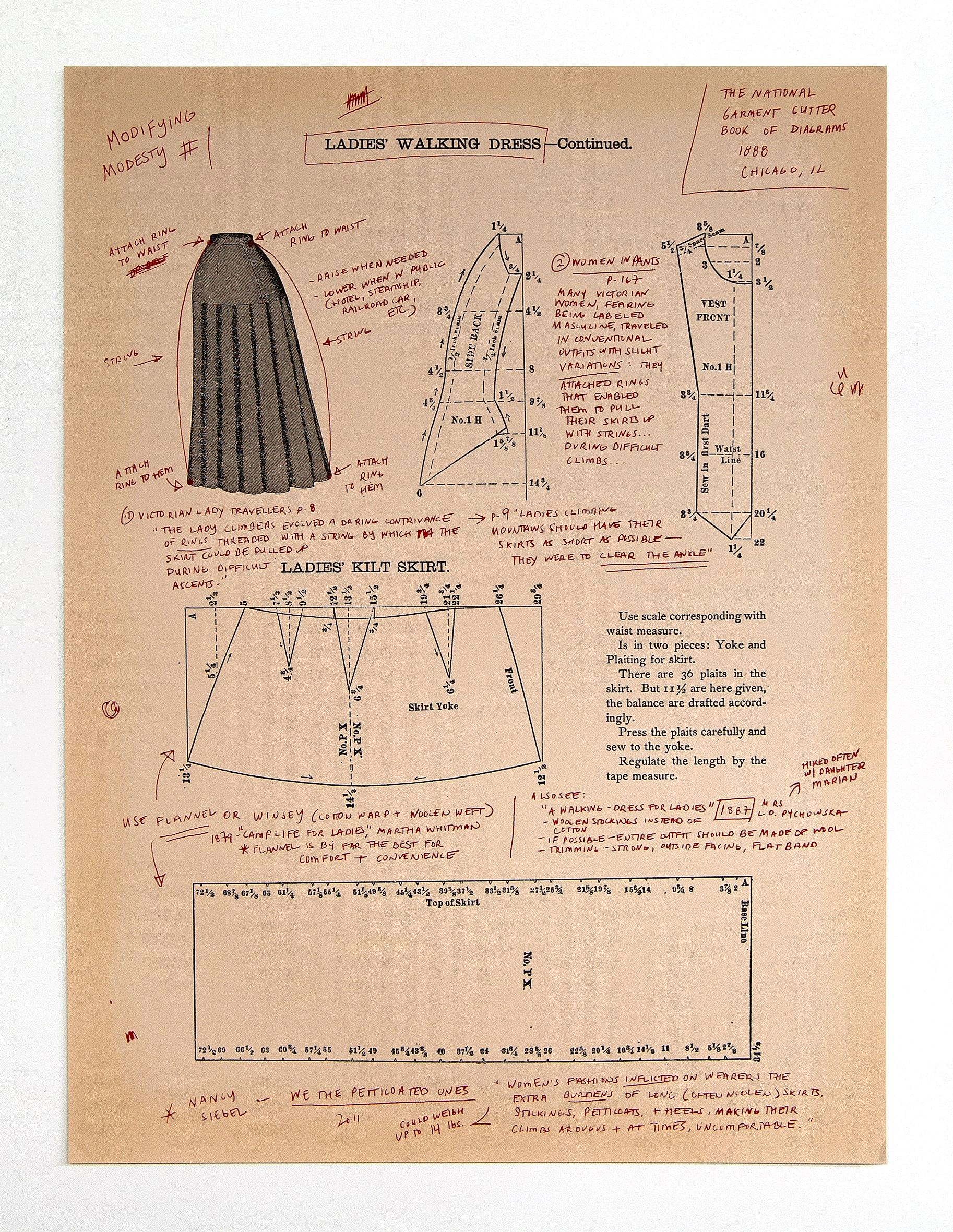

“Modifying Modesty” by Anna Plesset, 2022, letterpress, silkscreen, and handwork on Stonehenge, 20 by 15 inches, edition of 20, 5 AP, 2 PP, Courtesy the artist.

The show delves deeper into one specific limitation for women landscape painters: the challenge of how to hike in the restrictive women’s clothing of the late Nineteenth Century. A life-size enlargement of a tintype showing Barstow in her hiking gear opens the exhibition, and right next to it is her paintbox, which along with many of the artworks on view has been carefully saved by the Barstow family in the century since her death. Together, the picture and the paintbox convey the difficulty of navigating the actual terrain of the Catskills, Adirondacks and White Mountains, along with the fraught social terrain of postbellum America. There were ways to go about it, it turns out: a contemporary work by Anna Plesset, on view nearby, takes the form of an annotated antique dress pattern, showing how systems of pulls and cords modified long skirts for the hiking trails.

Kitted out in this way, Barstow painted highly accomplished views of scenery from New York to California and beyond, including multiple trips to Europe. Some of the works on view, like “Mountain Lake in Autumn,” are fully realized exhibition pictures in the formal idiom of the Hudson River School — distant view, framing foliage, eye-catching foreground details — while others, like “Pool in the Woods,” are more understated views of the forest interior, evocative of later Nineteenth Century ideas about how art, nature and spirituality intertwine. Indeed, “In the Woods” belonged to famed clergyman and orator Henry Ward Beecher (it is today in the collection of the Harriet Beecher Stowe House in Hartford, Conn.), evidence that Barstow had very high-profile clients indeed. “Pool in the Woods” is also interesting in that its composition is echoed in several other works in the show, including “Night in the Woods” and “Sunlight in the Woods,” exploring different effects of light, mood and time of day in much the same way European modernists like Claude Monet were doing at the same time.

“Night in the Woods” by Susie Barstow, 1890, oil on canvas, 20 by 14 inches, Georgia B. Gosnell Collection, Photograph: Hawthorne Fine Art, New York City.

The exhibition, as suggested by its title, exists in two parts, with “Susie Barstow and Her Circle” in the Cole site’s modern gallery space (a reimagining of Cole’s “new studio”) and “Contemporary Views” in the historic house where Cole and his family lived, also known as Cedar Grove. There is a little blurring of the boundaries in each place, with Anna Plesset’s aforementioned piece enhancing the historical works on view in the new studio and an important work by Sarah Cole — Thomas’s sister, and an accomplished artist in her own right — among the contemporary works of art in Cedar Grove. Sarah’s painting, on loan from the Albany Institute of History & Art, is a copy of Thomas’ Catskill “Mountain House,” also on loan; the two are seen together here for the first time since the Nineteenth Century. Notably, Plesset has a role in this liminal space as well as the one in the new studio; her “Value Study 1” copies Sarah’s copy after Thomas but leaves it unfinished — a reminder, says Menconeri, that “the labor of recovery, of recovering women’s voices in history, is never complete; it’s always being done.”

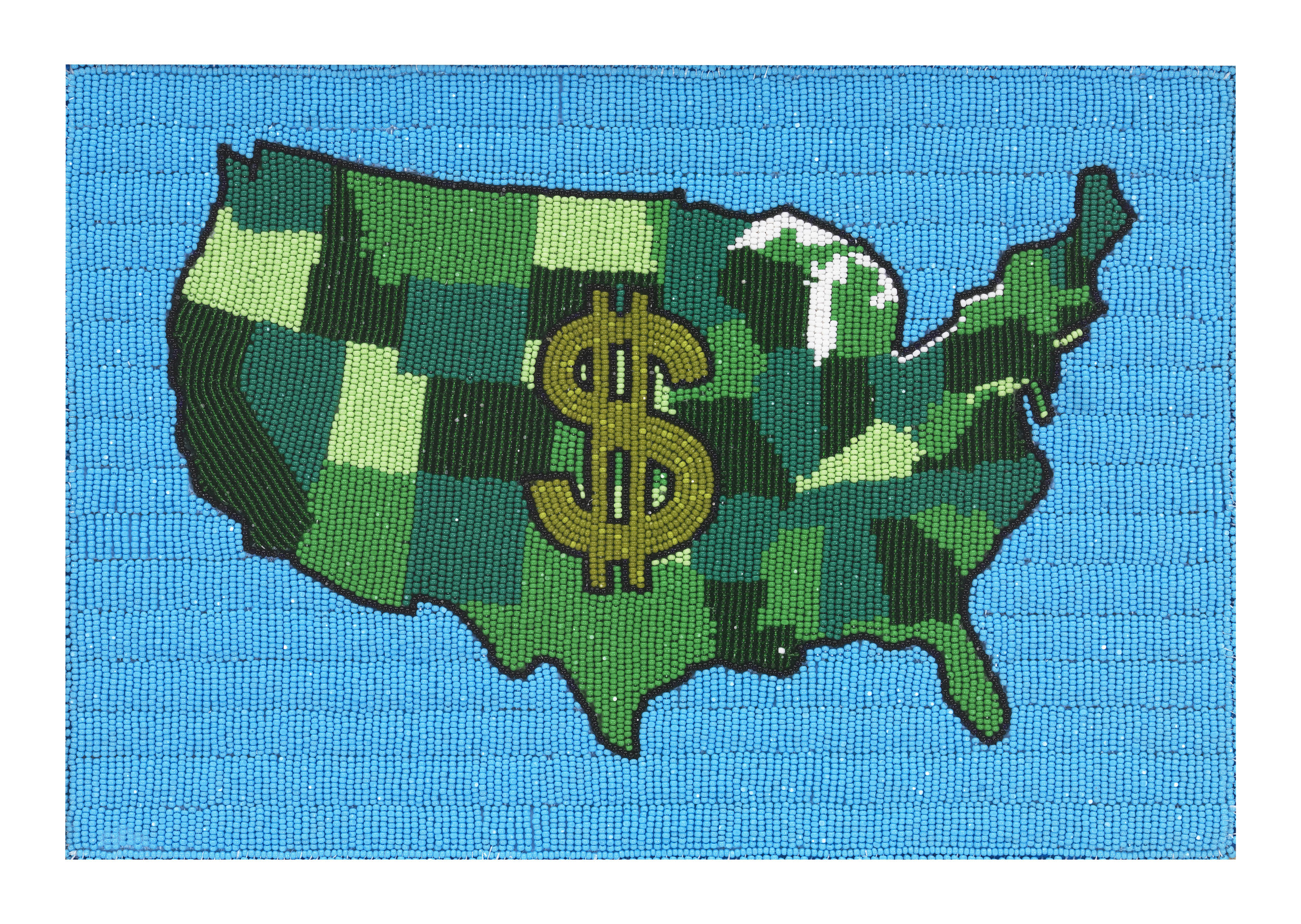

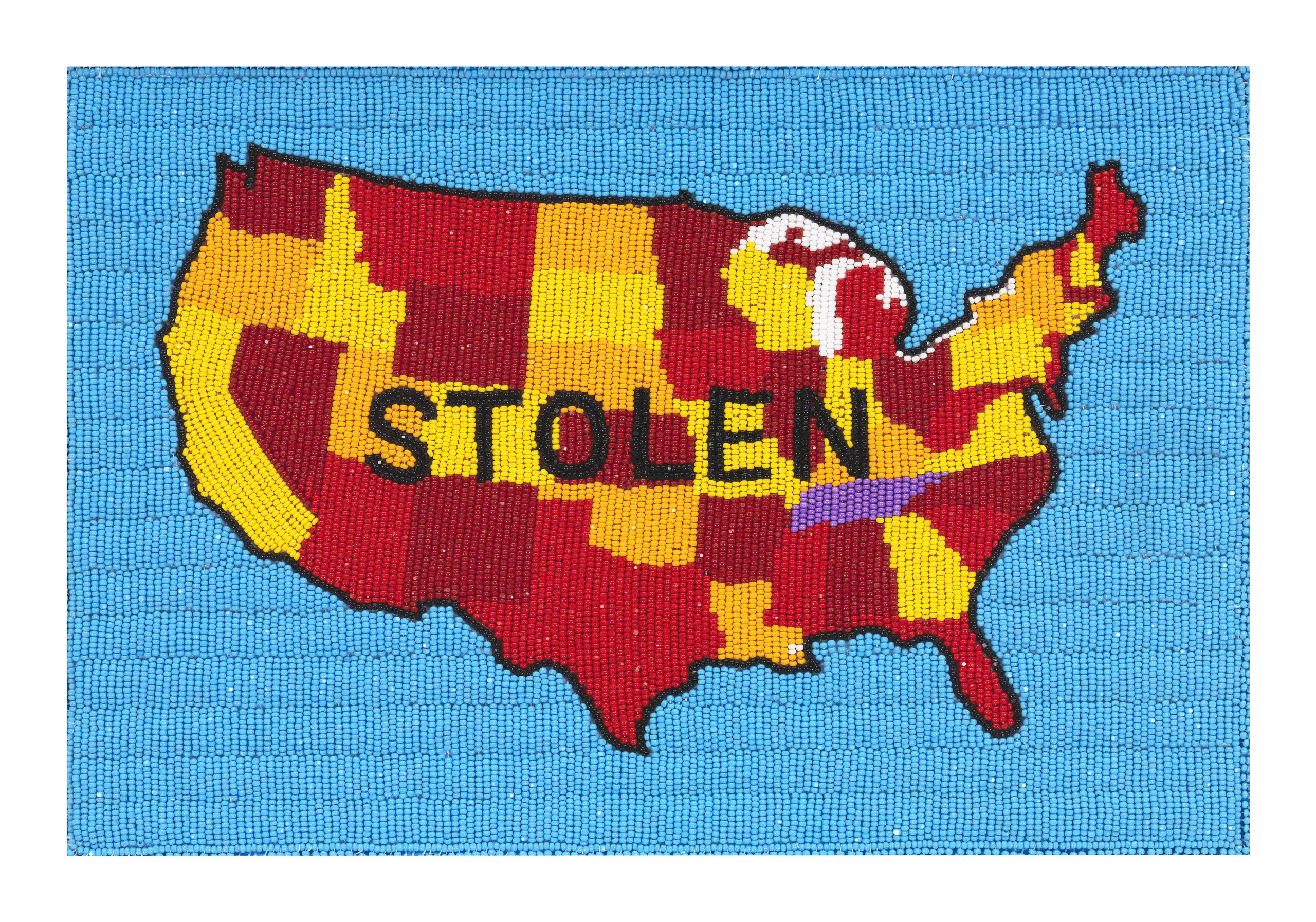

Left unfinished, with only the sky and a corner of foliage filled in at the upper left, Plesset’s work looks oddly map-like, with the sky reading as water and the foliage as land. Intentional or not, this creates a fascinating parallel to additional works on view in the same space (the second story sitting room of Cedar Grove) by the Indigenous artist Jaune Quick-To-See-Smith. In the painting “Unhinged (Map),” the outline of the continental United States is flipped on its head, with cartoon-like brackets around it suggesting motion and destabilization. More maps above the fireplace are smaller but no less striking; here the familiar US silhouette is rendered in careful beadwork, with each map bearing a beaded message: “She/Her/Hers,” “Stolen,” “$” and “Amerika.” These works and others deal forthrightly with topics that Barstow and her circle, as affluent Anglo-Americans, would likely never have considered including, as Malmstrom put it, “Who has the power to name the land, and who owns it?” as well as “Who is included in the stories we tell about it?”

“She, Her, Hers Map” by Jaune Quick-To-See-Smith, 2021, beads, 8 ¼ by 12 inches. Courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York City.

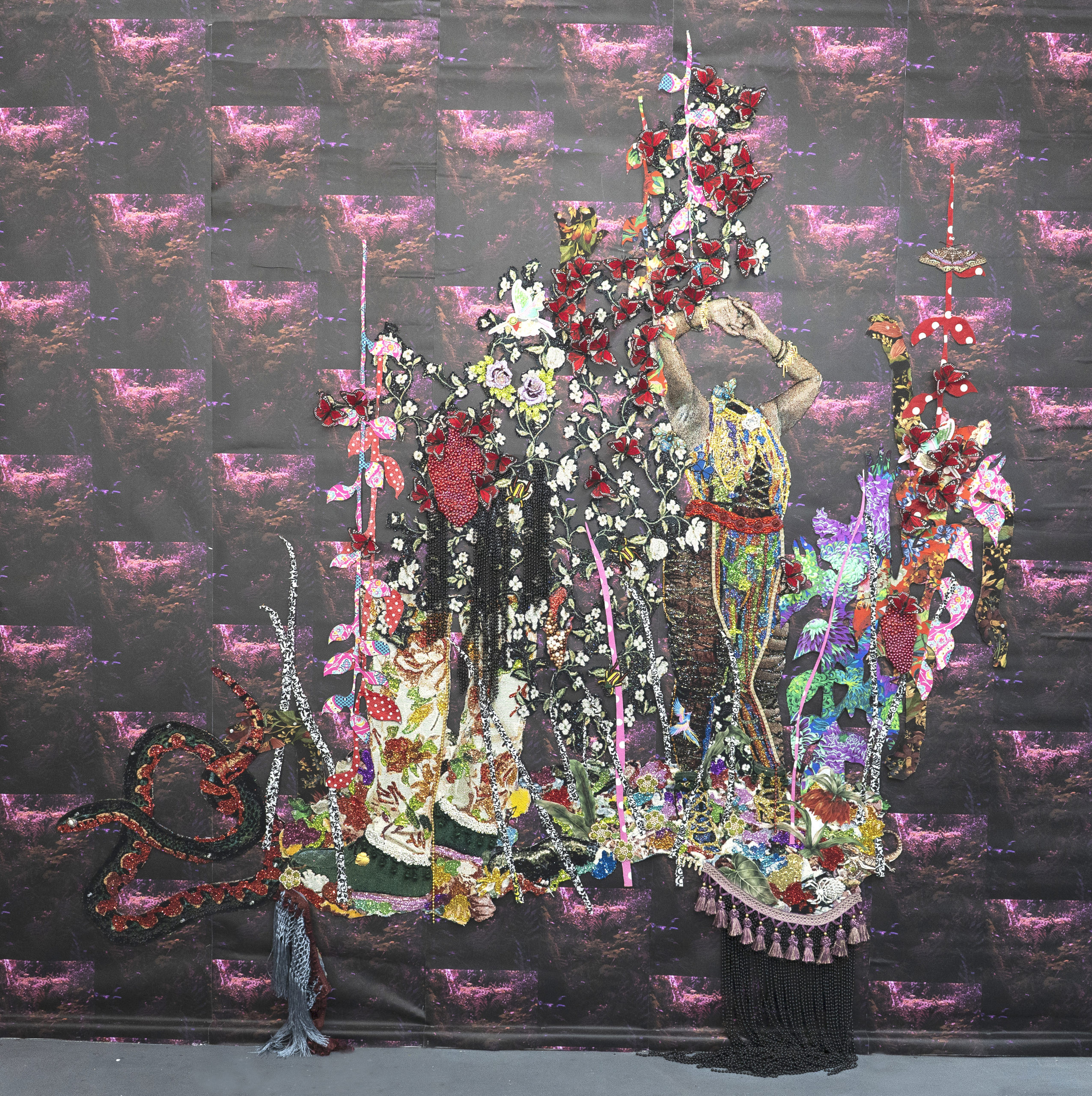

It may feel jarring to some visitors to have the work of contemporary women of color take up so much space in a historic house otherwise dedicated to a Nineteenth Century English/American painter. But the curators point out that Cedar Grove is, in fact, a very woman-centered space. Although Thomas Cole lived there, he never owned it; it was the property of his wife, Maria’s, family, and much of the unseen labor involved in running it as a semi-public artist’s space, before and after Cole’s death, was done by women. Then, too, the art that was displayed here during Thomas’s lifetime — his own work as well as Sarah’s and that of their friends and colleagues — was contemporary for its time. So perhaps it is not so much of a stretch to see Teresita Fernández’s series of “Small American Fires” paintings line the perimeter of the room the Coles used as a gallery space, or Ebony G. Patterson’s monumental baroque wallpaper installation taking primacy of place in the parlor.

The question of who we include in our histories — and art histories — is the subject of yet another work by Plesset, which on first appearance seems to be simply a copy of the catalog for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 1987 Hudson River School exhibition, “American Paradise” laid open to the page featuring Susie Barstow. But wait — Barstow was never in that exhibition, nor in the catalog. Instead, this is a clever intervention, a literal reinsertion of women landscape painters into a canon-forming event and publication. Further, the work on view is not a book at all but a trompe l’oeil sculpture; visitors cannot leaf through it to see who else it may discuss (to be clear, it’s not okay to touch it at all); instead, Malmstrom says, it “leaves the labor to us as the viewer [as to] what would fill these pages; who would these women be.” Similarly, a newly commissioned work by the Guerilla Girls, “Hudson River School Reality Check,” exposes the lacunae and challenges the myths of American landscape painting and art-historical canon formation.

“Stolen Map” by Jaune Quick-To-See-Smith, 2021, beads, 8 ¼ by 12 inches. Courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York City.

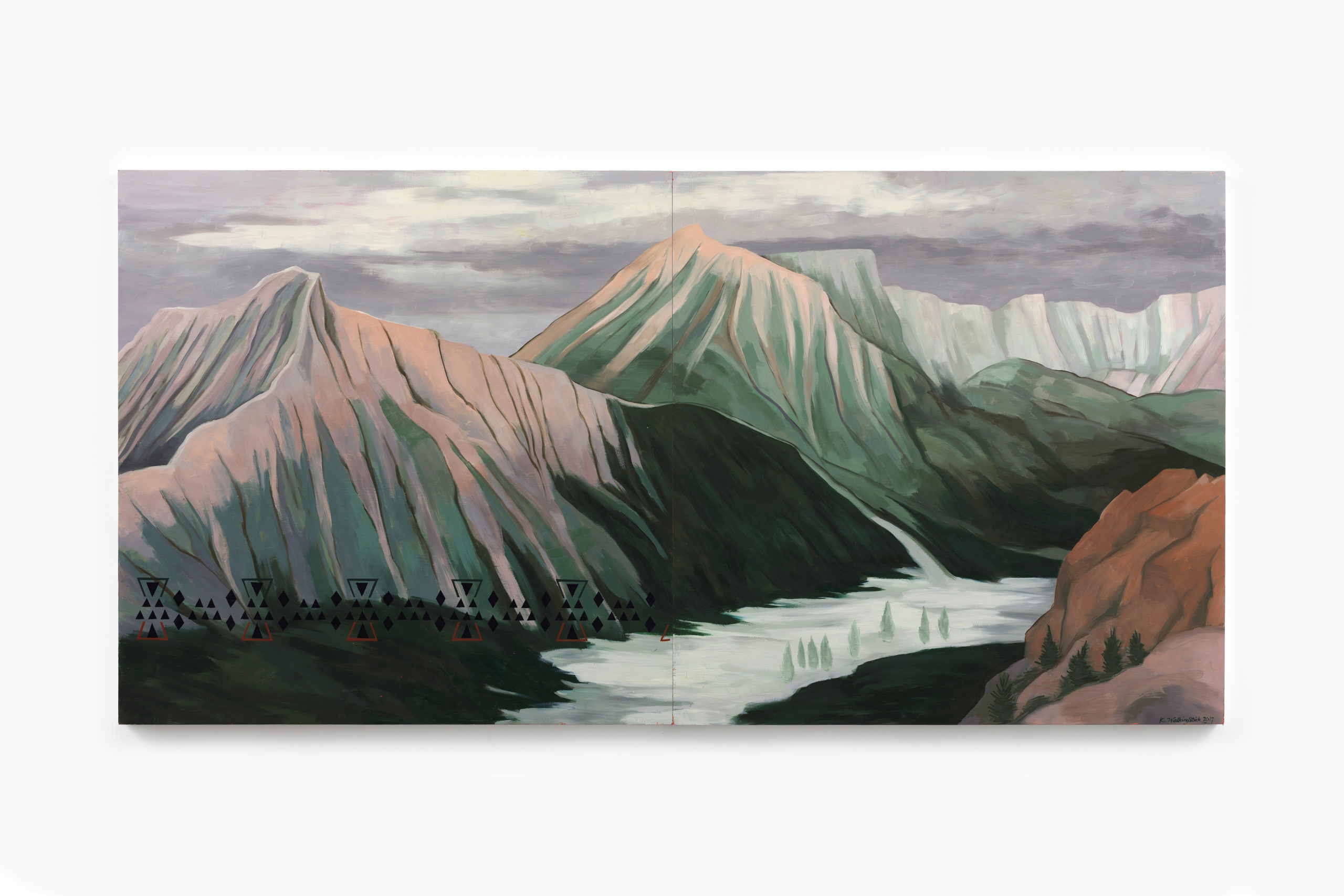

The Guerilla Girls piece represents the continuity of a kind of second-wave feminist art history that is now canonical in its own way, but this is further teased open by the intersectional work of a new generation, including the ethnic and ecocritical perspectives represented by Marie Lorenz, Tanya Marcuse, Mary Mattingly, Wendy Red Star, Jean Shin, Cecilia Vicuña and Saya Woolfalk. The shared message that human beings do not exist separately from nature but are wholly part of it is also evident in Kay Walkingstick’s monumental painting “Winter Passage,” a mountainous landscape not dissimilar in composition to those of the Hudson River School. Unique to Walkingstick’s rendition, though, is the Indigenous basketry pattern overlaid on the painting’s surface, hovering over the picture plane both to remind us that it is a picture and not reality, and to make the Native’s presence in the pictured landscape unignorable. Visually speaking, at least, you cannot get to those alluring mountains without encountering the heritage of those who lived, and still live, among them.

By weaving contemporary art in and among the historical pieces, the curators of “Women Reframe American Landscape” have adopted a similar strategy to Walkingstick’s: they have made it unignorable. At the same time, the visual appeal of the works draws you in and creates a space where you can begin to question why you have never seen some of them before, or why you respond as you do to seeing them in this place — or even to reconsider or reframe your perceptions of the Hudson River School itself. Engaging serious issues through beauty is something that Cole, an ardent and vocal environmentalist, understood out of the gate, and it is therefore only natural that his home furnishes a place to continue that lauded American tradition.

The Thomas Cole National Historic Site is at 218 Spring Street. The New Britain Museum of American Art is at 56 Lexington Street. For information, www.thomascole.org or www.nbmaa.org.