“Gassed” by John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), 1919. Oil on canvas, 90½ by 240 inches. Imperial War Museum, London

By James D. Balestrieri

PHILADELPHIA, PENN. – You will – and should – spend some time in front of John Singer Sargent’s 1919 masterpiece “Gassed,” a rare loan from London’s Imperial War Museum, on view in “World War I and American Art” at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) through April 9. This arresting image, notable for its sheer size and complexity, reflects and amplifies a scene Sargent witnessed outside a dressing station behind the lines at La Bac-de-Sud, France. The figures of soldiers – living, wounded, blinded, dying – move from left to right. They are accompanied by the notion of duty having been done, stoically, without complaint. Some soldiers are led away. The rest wait on the ground, in contorted attitudes resembling death, sleep, nightmare – the blind leading the blind. Patriotism gives way under the weight of suffering. Indictment overmasters heroism. The sun, low between the lines of blind men walking, is an eye burning through a fog – of mist, of gas, of both? – an eye – God’s eye? – that is cold, unblinking, judging.

If “Gassed” were on exhibition alone, it would be worth the trip to Philadelphia. But “World War I and American Art,” coming as we enter the hundredth anniversary of the entrance of the United States into the war, is much more than that. Encompassing, among other things, war posters, aerial photography, political cartoons, the roles of African Americans and the response of Modernists, the show casts a deep, broad net. It features approximately 160 works by 80 artists and embraces a range of styles, views and emotions.

World War I, when you boil it down, was a family squabble between the various European crown heads – related by marriage, blood or both – over the spoils of colonialism in Africa and elsewhere. Coupled with the nationalist aspirations of subject peoples, the squabble smoldered and set the continent ablaze. I mix metaphors here, but the politics are a jumble.

From 1914 to 1917, President Woodrow Wilson kept his promise to maintain neutrality and keep the United States out of European entanglements. But during those years, trade with Great Britain, including military hardware, soared. Commerce with Germany plummeted. German submarines, also new to war and the world, began to target American shipping. When they sank the Lusitania, a British liner carrying a number of American passengers, the drumbeat for war began. In April 1917, the Unites States declared war on Germany.

“The Germans Arrive” by George Bellows (1882–1925), 1918. Oil on canvas, 49½ by 79¼ inches. Courtesy Ian M. Cumming

Artists played a role even before 1917. Reports of German atrocities galvanized George Bellows, initially an opponent of the war, into action. Bellows, channeling Goya, painted and made prints of rape, forced labor and the murder of children by gleeful monsters in German uniforms. Masterfully done yet extremely difficult to contemplate, these works were meant to rouse Americans in support of military action.

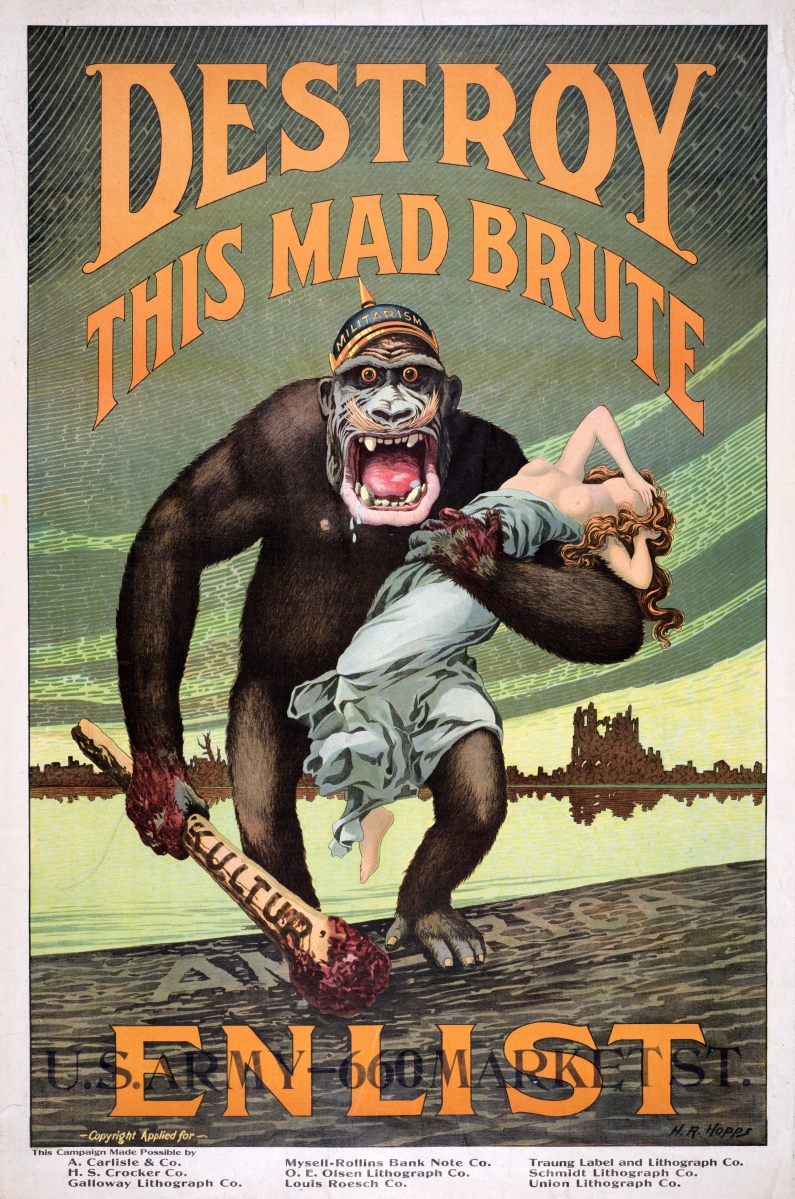

One of a number of fascinating facets of “World War I and American Art” is the rise of the citizen consumer in campaigns adopted by American manufacturers in support of the war effort, described in a catalog essay by Pearl James. Sugar, for example, was for the boys overseas; honey and maple syrup were to be substituted for sugar at home. Consumers, organizing themselves into committees, sent suggestions for slogans and images to companies and government organizations. The primacy of words that had dominated advertising yielded to the image and the catchy slogan. Recruitment posters and posters encouraging citizens to do their duty, many done by celebrated artists like Howard Chandler Christy and James Montgomery Flagg, proliferated in schools, in plants and along roadsides. This binding of commerce and patriotism has only deepened in the decades since the First World War, embracing, among others, sports, the auto and oil industries, and environmentalism. The relationship between the NFL and the American Armed Forces springs immediately to mind as a prime example of this symbiotic relationship.

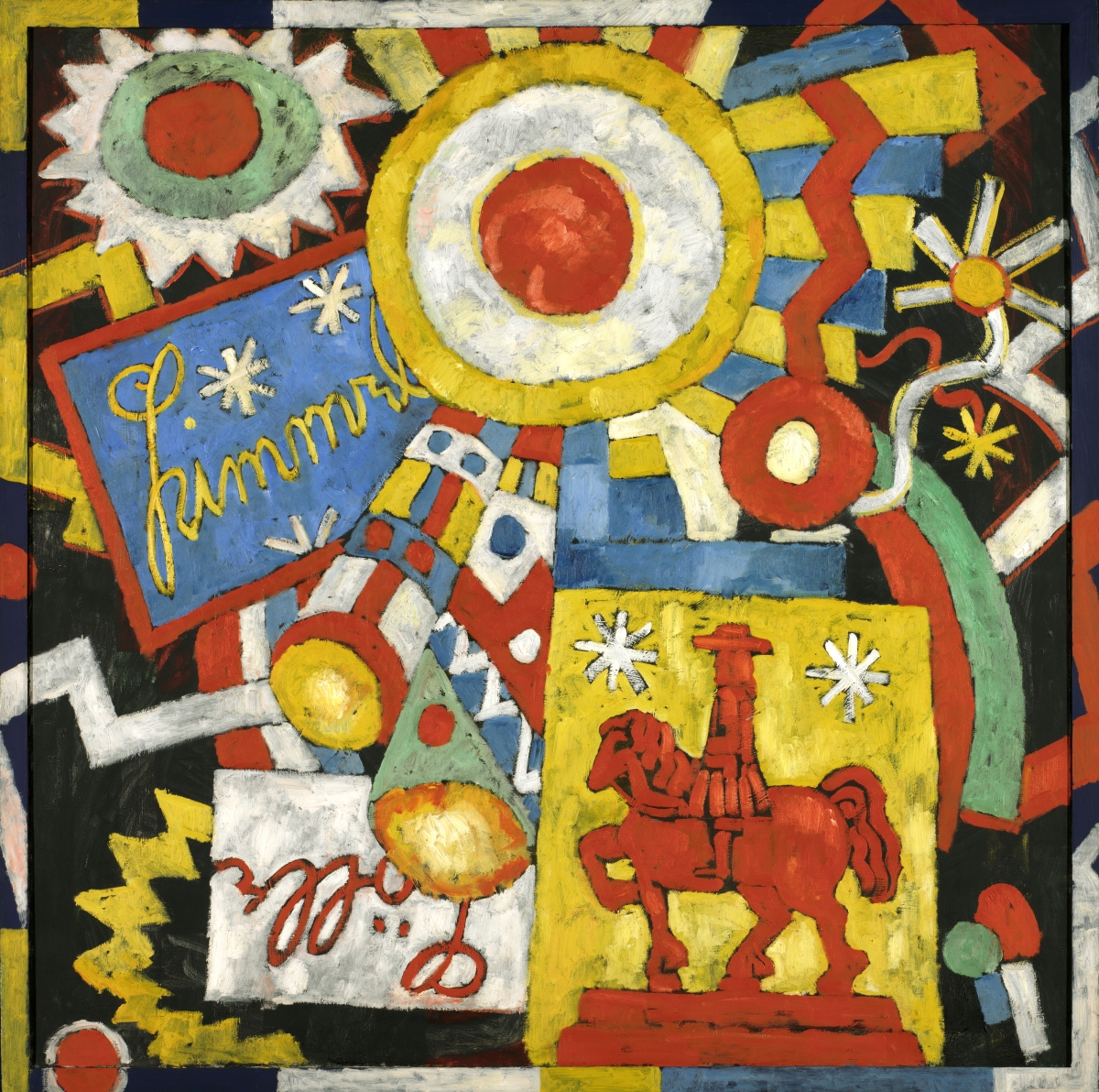

Of even greater interest, perhaps, is the influence of the airplane and, by extension, aerial photography and camouflage on artists like Edward Steichen and Homer Saint-Gaudens, who served in these respective fields. Steichen, one of the pioneers of American photography as art, commanded the photographic division of the American Expeditionary Forces, the name for the US Army in Europe. Saint-Gaudens, son of the eminent sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, wrote one of the seminal works on camouflage, focusing on deceiving aerial photographers. “The [aerial] camera,” Saint-Gaudens asserted, “is a most accurate witness, and the photographs will always record something.” The task of the camoufleur consisted of understanding, and undermining, this new capability.

“The art of camouflage,” Saint-Gaudens continued, “lies in conveying a misleading impression as to what that something means.” This new approach to military intelligence introduced the idea of a battlefield as an artistic abstraction to be manipulated, read and penetrated. Philosophies of concealing and revealing added new layers to the old concepts of appearance and reality, perception and meaning in art. Soldiers, meanwhile, are folded into that abstraction. They become tactical pieces in an increasingly technological theory of war.

African American leaders like W.E.B. DuBois saw the war as an opportunity for blacks to serve their country and advance the cause of equality. Rare images from his periodical, The Crisis, highlight the heroism and sacrifice of African Americans. Despite their outstanding service, African American troops were segregated, treated poorly and distrusted. They returned to an unequal America.

“The End of the War: Starting Home” by Horace Pippin (1888–1946), 1930–33. Oil on canvas, 26 by 30-1/16 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art

With its frame of tanks, grenades and helmets, “The End of the War: Starting Home” by Horace Pippin, one of the famed Harlem Hellfighters, has a fast, folky, journalistic feel, despite being a painting he worked on for three years between 1930 and 1933. In his catalog essay, David Lubin asserts, “Perhaps the relative ‘invisibility’ of the black soldiers in this heavily painted and much-reworked tableau had something to do, in the artist’s mind, with their relative invisibility in American culture at large, in which, after the initial flurry of homecoming glory, they were largely ignored by white society for their wartime sacrifices and heroism.” You can also see them as camouflaged, as men rising out of the blasted earth, the earth that in this theater of war is broken and taken for granted, indomitable spirits vanquishing the ghostly pale Germans. You can see it both ways.

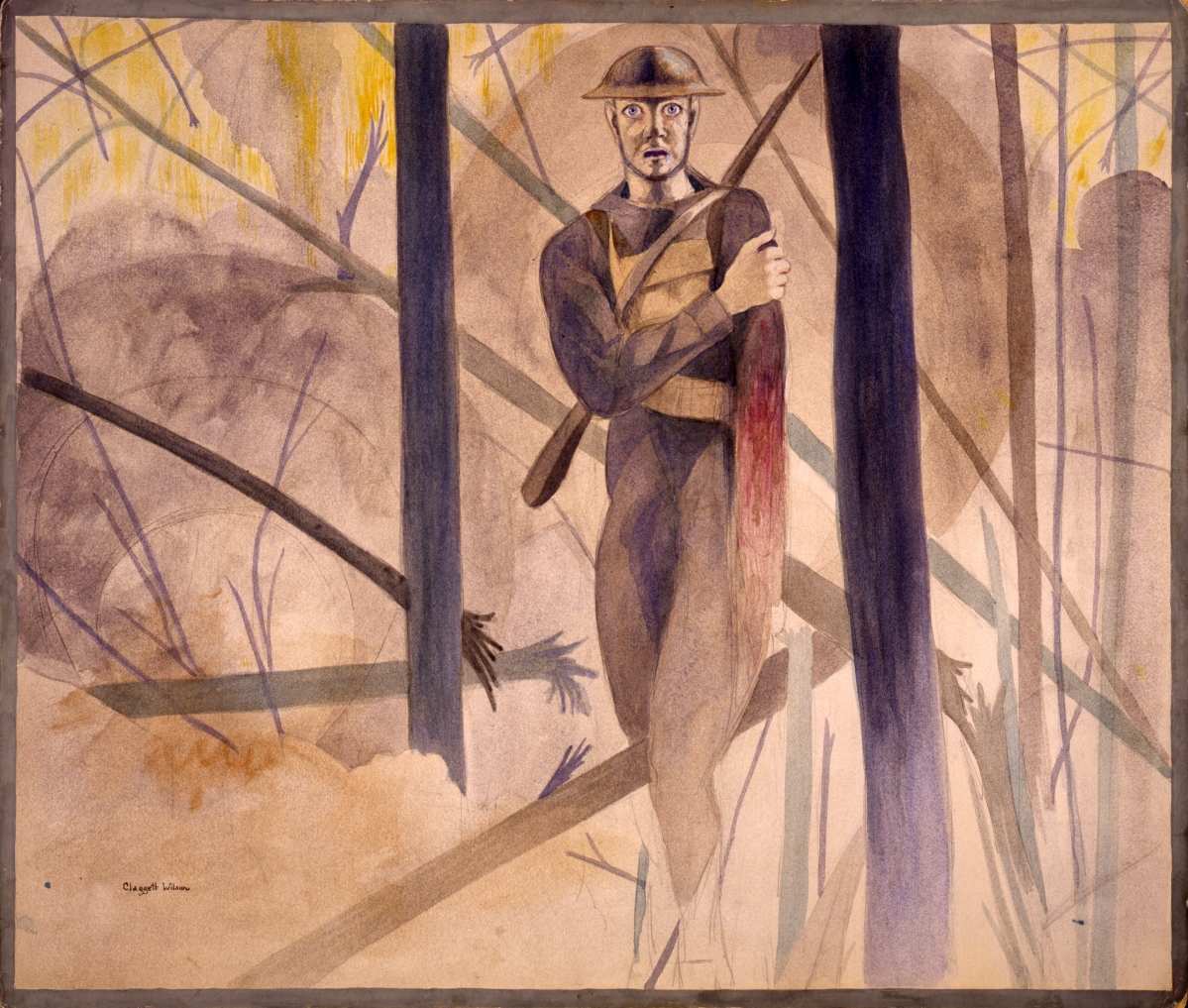

Another soldier-artist, Claggett Wilson, echoes the sensibility of Charles Burchfield, who is featured in a fine essay by Alexander Nemerov. Burchfield opposed the war, eventually joined up, but never left the United States. His wartime paintings articulate a living, quivering, tentacular vision that rises unpeopled out of the natural world. In Wilson’s war, however, soldiers on both sides are lost creatures in Dantean woods, meat for the political grinders that initiate and perpetuate the conflict. In “Runner Through the Barrage, Bois de Belleau, Château-Thierry Sector; His Arm Shot Away, His Mind Gone,” for example, the delicacy of Wilson’s transparent watercolor plays against the thick blasted forest and the soldier holding what is left of his left arm, staring out at you without seeing you, feeling only the excruciating pain of his wound, seeing only the terror and hopeless isolation of his inhuman condition.

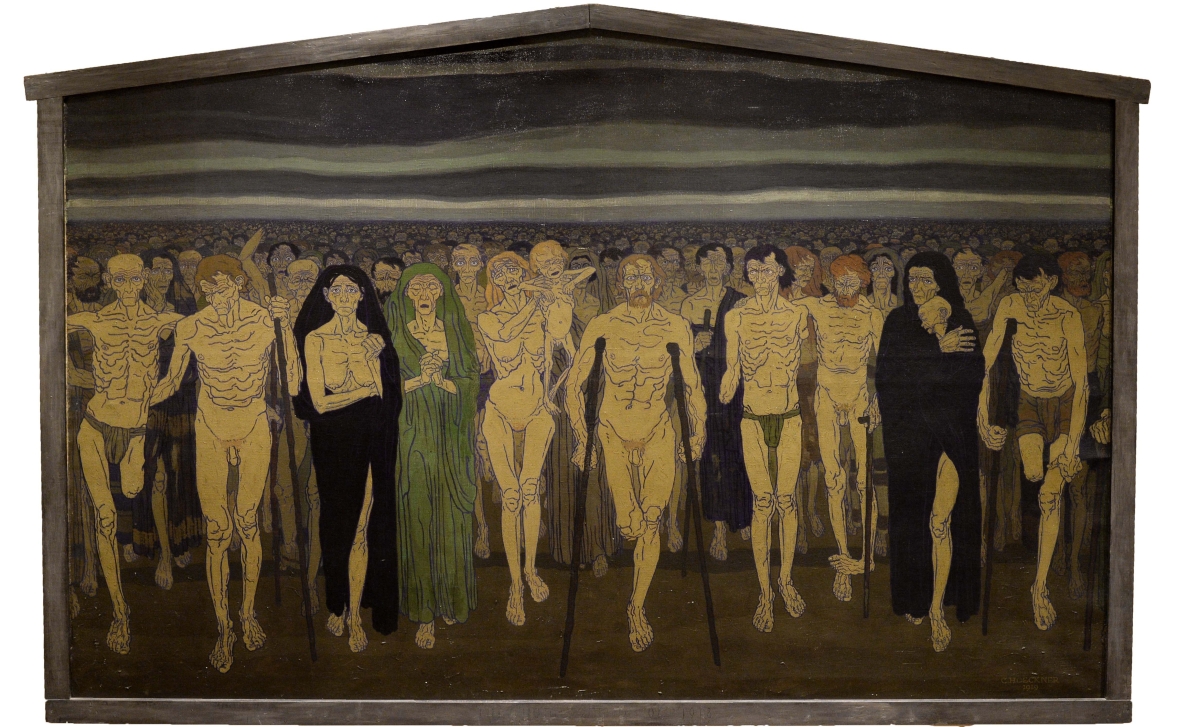

One artist, Ivan Albright, found a kind of personal spirituality in the physical materiality and corporeality of the human body as he spent his days documenting wounds in American Expeditionary Force hospitals near the front lines. How the body healed through the magic of medicine and some intangible, cellular process fascinated the artist and informed his work for the rest of his life. As Robert Cozzolino observes in his catalog essay, “Albright’s philosophy and representational strategy was born out of witnessing flesh healed by intangible powers within the body during the war. It was an attempt to account for that which is unseen, even to suggest, by showing its opposite, the soul.” His later work, pictorially unique, sees beauty in ugliness and spirits everywhere, as if the wounds and scars we all bear, within and without, and the stories they tell, are the stuff we are made of, our identities.

World War I was the “war to end all wars.” Only it wasn’t. While looking at the art and reading the catalog, the quote, “Only the dead have seen the end of war,” which I have read on the walls at the Imperial War Museum and the West Point Museum, echoed in my mind. In a speech delivered at West Point, Douglas MacArthur attributed the words to Plato, but, as I discovered, philosopher George Santayana wrote it in 1922 in response to the carnage of World War I. It is natural, perhaps, to wish that sentiment to be ancient, remote from us. In fact, it is too contemporary and always with us. As William Wordsworth observed, “The world is too much with us; late and soon.”

“World War I and American Art” will travel to the New-York Historical Society and the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in the spring and fall of 2017. The accompanying catalog, World War I and American Art, is edited by Robert Cozzolino, Anne Classen Knutson and David M. Lubin with additional contributions from Pearl James, Amy Helene Kirschke, Alexander Nemerov, David S. Reynolds and Jason Weems. The 320-page illustrated volume is published by PAFA in association with Princeton University Press.

“World War I and American Art” is on view in PAFA’s Samuel M.V. Hamilton Building at 128 North Broad Street. For information, 215-972-7600 or www.pafa.org.