“The Bombardment of Algiers, 27 August 1816” by George Chamgers, 1836, oil on canvas. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. Greenwich Hospital Collection.

By James D. Balestrieri

LONDON — It isn’t wrong to say that we do everything we can to preserve our mythical images of pirates. It also isn’t wrong to say that Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island is my favorite novel. Still, since I was a kid, I reread it almost every year. Me, landlubber, prone to seasickness in the shower. Objectively, we know that pirates, real pirates, were — and are — not at all romantic, not at all the honor-among-thieves comedic rascals depicted in Peter Pan and Captain Pugwash; Gilbert and Sullivan’s opera; the Pirates of Penzance, and Cecil B. de Mille’s classic film The Buccaneer, in which Jean Lafitte (or Yul Brynner, take your pick) secures victory against the invading British for our fledgling republic at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815 (this happens to be true). Even when we read about renewed Somali piracy in the Red Sea, as I did just this past weekend, we put that news in a box and watch trickster Jack Sparrow and honest Will Turner fence and face off in Pirates of the Caribbean for the umpteenth time. This mixing of myth and reality — that is, our preference for myth and a renewed understanding of the complexities of the reality of piracy — form the subject of “Pirates,” the new exhibition at The National Maritime Museum, part of Royal Museums Greenwich. As the museum literature states, the objects in the exhibition were selected to trace “the changing depictions of pirates throughout the ages and revealing the brutal history often obscured by fiction. While sometimes portrayed as tricksters or scoundrels, pirates are primarily swashbuckling adventurers associated with lush islands, flamboyant dress and buried treasure. ‘Pirates’ will deconstruct these myths and illuminate the realities of pirate life…”

Divided into three parts — “The Pirate Image,” “Real Pirates” and “Global Pirates” — the exhibition takes off from the Seventeenth Century and the beginning of the golden age of piracy, when Spanish, French and English ships, laden with precious cargo — gold, silver and, yes, enslaved Africans — were crisscrossing the Atlantic, attracting the first of the famous pirates. But the definition of pirate is muddled from the first. Why? The first pirates were what we would call privateers, pirates authorized by governments to plunder the ships of other countries. One nation’s privateer was another nation’s pirate. Sir Francis Drake, for example, was a privateer and hero to the English. In Spain, he was branded a pirate. Jean Fleury was a French naval officer and privateer. In 1522, he intercepted the Aztec treasure of Cortés on its way to Spain. Imagine what the Spanish called him. From that moment, the “yo-ho-ho” of the high seas called out.

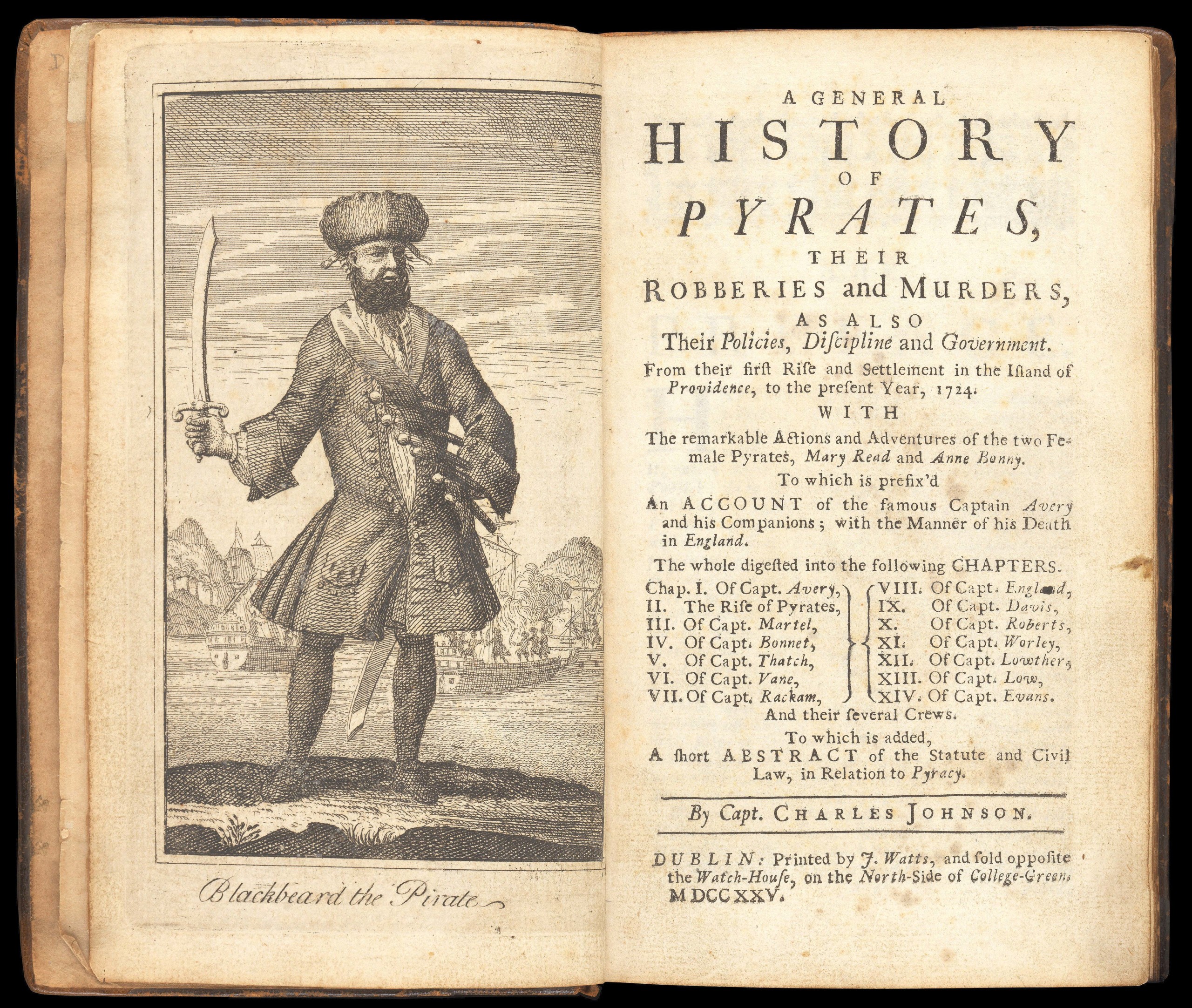

A General History of the Pyrates by Captain Charles Johnson, published by J. Watts, 1725. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

A central object in the exhibition is the first book to trace the histories — and remember, there’s no history without the word “story” — of the most notorious pirates. The 1724 book A General History of Pyrates, their Robberies and Murders by Captain Charles Johnson was an instant hit. In the book, which also bears the important subtitle, As Also, Their Policies, Discipline and Government, Johnson quotes the Welsh pirate Bartholomew Roberts (the model for the Dread Pirate Roberts in The Princess Bride) about the attractions of piracy: “In an honest service there is thin commons, low wages and hard labor. In this, plenty and satiety, pleasure and ease, liberty and power; and who would not balance creditor on this side, when all the hazard that is run for it, at worst is only a sour look or two at choking? No, a merry life and a short one shall be my motto.” Roberts was the pirate captain who drew up the first pirate code of honor. He emancipated enslaved Africans and invited them to join his crews, and he was noted for treating hostages well — sometimes. It’s the flag of Black Bart — as he was known — that becomes the Jolly Roger. In short, despite Johnson’s disdain for pirates, stories such as his created the image of the buccaneer we know and love. The golden age ends with the death of Roberts in 1722, though piracy continued, especially off the Barbary Coast of North Africa and which ended with the British Bombardment of Algiers in 1816, commemorated with a silver-gilt table centerpiece by Paul Storr of London, commissioned by British officers at Algiers a year later for presentation to their commander, Admiral Pellew. Richly detailed, the centerpiece depicts “the fortress at Algiers, bristling with tiers of guns, and scenes of the bombardment. The surrounding figures represent British seamen fighting Algerians and releasing Christian captives.” In an 1836 oil by George Chambers, “The Bombardment of Algiers, 27 August 1816,” the engagement gets heroic treatment, just shy of Turneresque in its balance between realism and atmosphere as Algiers, the pirate haven, succumbs, though at great cost.

The egalitarian view of pirates, however, is based in fact. Johnson, for example, wrote about two women who captained pirate ships, Mary Read and Anne Bonny. Perhaps a third of the Caribbean pirates were fugitive slaves; some became captains, all had an equal vote. In popular culture, the television show Black Sails, a revisionist prequel to Treasure Island, takes an unflinching look at the violence and the political, social, racial and sexual complexities of the era. Equality on the quarterdeck of a pirate ship has a counterpart in the American Revolution in John Glover’s regiment of sailors from Marblehead, Mass., who saved the American army after the Battle of Brooklyn and ferried them across the Delaware to victory in Trenton, N.J.

Table centerpiece commemorating the Bombardment of Algiers, silver-gilt, by Paul Storr, London, 1817-18. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. The British officers at Algiers commissioned this centerpiece from the leading London silversmith Paul Storr. They presented it to their commander, Admiral Pellew. It shows the fortress at Algiers, with tiers of guns and scenes of the bombardment.

Glover’s sailors were cod fishermen by trade. When the British commandeered the Grand Banks and began to impress Glover’s crews, many of the fishermen turned privateer. The captain joined the rebellion. As David Hackett Fisher writes in his book, Washington’s Crossing, “The regiment also reflected the ethnic composition of New England maritime towns. Indians and Africans sailed in Yankee ships… They also enlisted in Glover’s regiment. He knew these men as shipmates and welcomed them to his command. Others in the army did not approve… At first, George Washington was not happy about the enlistment of African Americans, but after much discussion he worked out a series of compromises… In that process, the Continental Army, beginning with the Marblehead regiment, became the first integrated national institution in the United States.” And where did most of the Marblehead regiment go after Trenton? Back to Massachusetts, to privateering, pilfered the British ships that had plundered their livelihood.

Jean Lafitte, as I mentioned, along with his superb cannoneer, Dominique Youx, turned the tide at the Battle of New Orleans. Lafitte was a smuggler, pirate, privateer and slave trader, tolerated in Louisiana because he seemed to be able to provide luxury goods where no one else could. Did he die in battle off the coast of Central America? Did he rescue Napoleon from St Helena and bring him to New Orleans where the two of them lived to old age? Did he vanish into the swamps of Louisiana or those of Galveston Island? Whatever the case, Lafitte simultaneously vanishes and emerges into pirate lore and myth.

Later in the Nineteenth Century, South Seas pirates arise and chieftains such as Shap Ng-tsai become legends. A hanging seized from one of his pirate junks in 1849 is one of the outstanding objects in the collection taken from a shipboard shrine, the hanging depicts Ziewi Dadi, one of the Four Heavenly Emperors in Cantonese cosmology, a god who calmed the waters and storms and protected mariners. Even a pirate lord, it seems, looked for a little help from above.

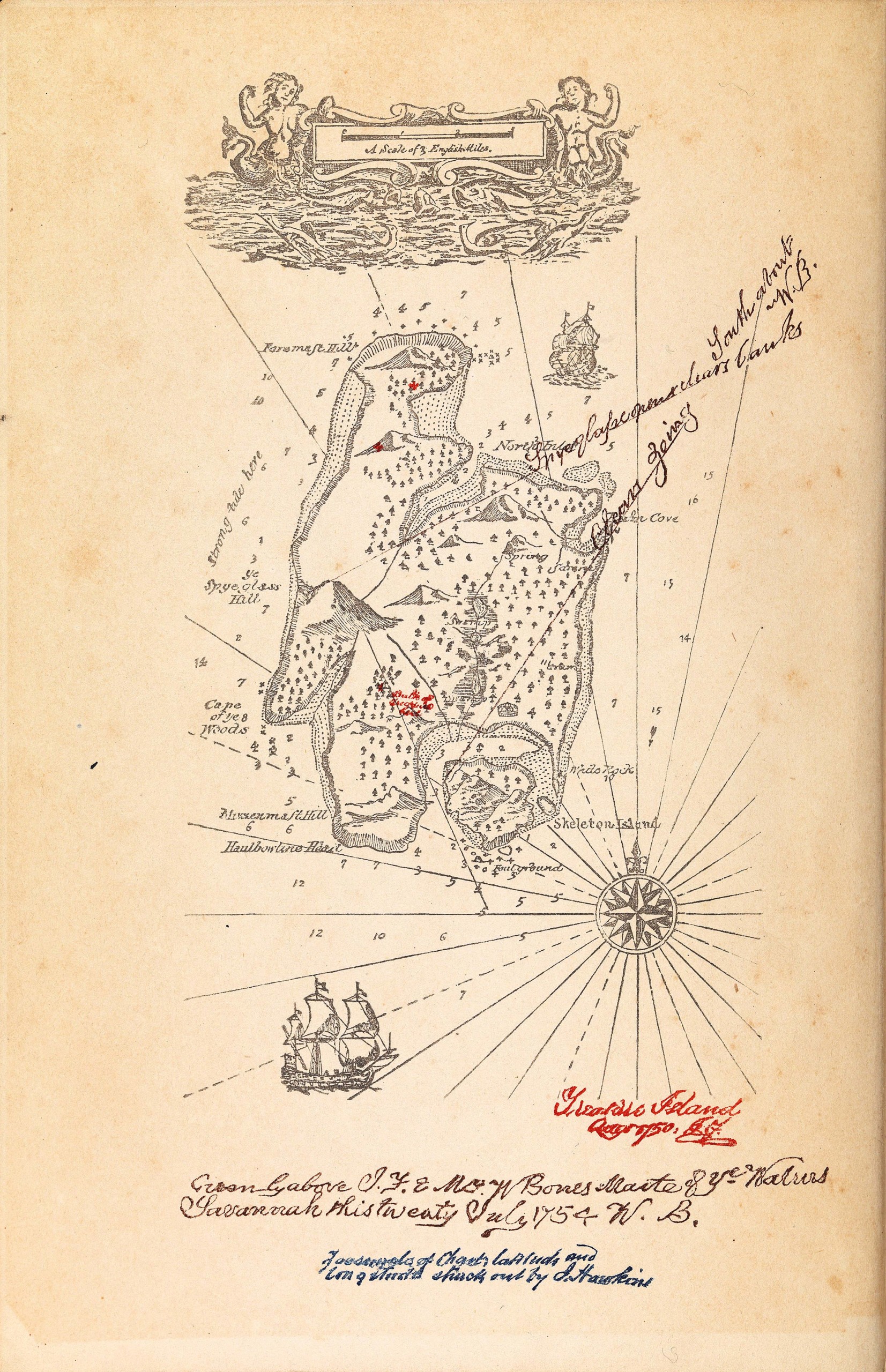

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson, published by Cassell, London, 1886 © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. The first edition of Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson, published in 1883, included a map drawn by the author. The map was an integral part of the story and was designed to spark readers’ imaginations about the adventure.

Treasure Island, Stevenson’s 1883 classic, is where the modern myth of the pirate comes from. The treasure map. X marks the spot. Walking the plank. Aarrgh! “Fifteen men on the dead man’s chest…” and all the pirate jargon we spout on Talk Like a Pirate Day (annually September 19). And Long John Silver as the devious, brilliant, rascally villain we love. From there to the thousands of episodes of the Japanese manga and anime series One Piece, where Monkey D. Luffy and his band of Straw Hat Pirates fight monsters and race other buccaneers for treasure, it’s a straight line.

Those Somali Pirates and their recent return actually epitomized the notion of pirate as outlaw, as a kind of maritime Robin Hood. Piracy in Somalia begins among fishermen, angry at the enormous, unregulated fleets from Iran, China and elsewhere scouring the shoals with their miles-long nets, making it impossible for them to earn a living. It’s a David and Goliath story. The little local guy versus the powerful invaders. But then they become something more. Organized. Armed. Violent. Why are they back? Houthi attacks on commercial shipping in the Red Sea has left the waters unregulated yet again, opening the way to illegal fishing. The Somalis call the big trawlers pirates. The world calls the Somalis pirates. No doubt the British called the Marblehead regiment pirates. No doubt the Marblehead cod fishermen called the British something worse.

In the end, perhaps, pirates appeal to ideas of freedom, the wishful thinking that human beings, left to themselves, will organize themselves in rational ways, never mind the social Darwinism at play. To us, from the safety of our lives, a pirate ship is a self-contained world, an ongoing sociological experiment and something in that is attractive to us. Or maybe it’s the sails. Or the cannons. Or the sea shanties.

My affection for “gentlemen of fortune,” as Long John Silver called them, and Treasure Island, began with an album of 78 records that had belonged to my older brother, in which Basil Rathbone voiced Silver. I had thought it long lost, sunk forever in the Davy Jones’s Locker of life and memory, right beside the skeletal hulks in William Lionel Wyllie’s 1890 painting of that realm of wrecks. Then, not long ago, I stumbled upon a pristine copy in a library book sale, remaindered and unwanted. Three bucks. One pirate’s discarded dross is another buccaneer’s chest of gold. I think I’ll go listen to it now. Yo-ho!

“Pirates” is on view at the National Maritime Museum until January 4.

The National Maritime Museum is at Romney Road in the National Maritime Museum Gardens. For more information, www.rmg.co.uk/national-maritime-museum.