Boxed balance with weights, Cologne, Germany, 1699. Produced by Berndt Odental (weights) and Jacob Heuscher (balance). Courtesy of the American Numismatic Society, New York, 1930. Alan Roche photo.

By James D. Balestrieri

NEW YORK CITY — “Money makes the world go round.” “Money is the root of all evil.”

Contradictions.

“Medieval Money, Merchants and Morality,” the new exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum demonstrates that these contradictions have been with us since time immemorial, whether we humans were bartering cows or cowrie shells, bushels of wheat or brides, or using discs of precious metal, pieces of paper or pixels on a screen as agreed-upon media of exchange.

Medieval Europe — by which the curators of the exhibition mean, roughly, the Twelfth through the early Sixteenth Centuries — is an especially fascinating era to explore in economic terms, an era that witnessed the rise of banking and lending, and the adoption of currency standards and paper money, the invention of insurance, labor shortages and the rise of guilds in the wake of the Black Death, the growth of antisemitic stereotypes around money and resultant official policies against Jews, and the rise of exchange — complicated by ideological conflict — with the Islamic world and the Far East. Given the fallout from the recent pandemic and the concomitant stresses on relations within and between races, points of view and nations, “Medieval Money, Merchants, and Morality” seems simultaneously prescient and timely.

Strict notions of usury, founded in scripture, held sway at the beginning of the Medieval period. These gradually gave way to accommodations between the church and the mercantile class as merchants supplanted trade in goods with monetary transactions and the economy expanded as a result. Large donations to the church surely eased this transition as well. Still, wherever money flowed, morality wasn’t far behind. Avarice, one of the seven deadly sins, was what we might call a gateway sin, the greed that leads to other, more forbidden desires and excesses. What might be of even greater interest to us is the development of the concept that money multiplied in an “unnatural” way. That is, investment made money, a sterile thing, grow, multiply, procreate — choose your own verb — without biology. This is why, in many medieval illuminations, miserliness appears on the same page with images of Eve or of animals, because humans and animals multiply according to the laws of nature and of God.

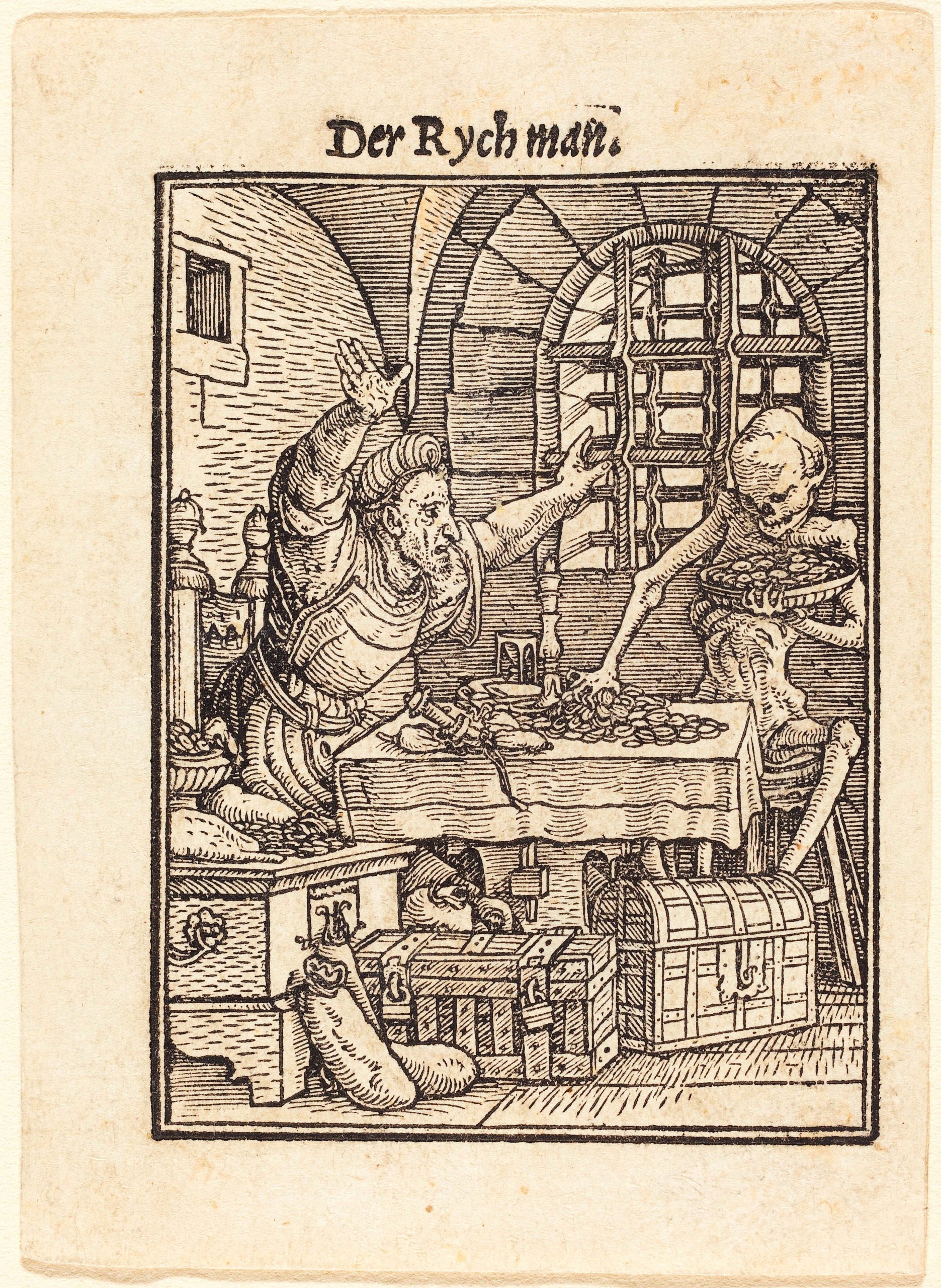

“Death and the Miser” by Hieronymus Bosch, circa 1485-90. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Samuel Kress Collection, 1952.

On loan from the National Gallery, Hieronymus Bosch’s oil, “Death and the Miser,” painted circa 1485-90 is — to me at any rate — the work that the other objects in the exhibition flow into and out of. Like a page out of a graphic novel whose panels have been melded into a single image composed of several images, the vision of demonic tempters — rodent, amphibian and chiopteran (batlike) — using money as bait, while an angel and the light of the crucifix contend for the sinner’s soul and Death peeps round the door, awaiting the result, is direct and somehow delectable. Unlike so many of Bosch’s works, there is no code to decipher, no symbols to unpack. The warning to all, despite its pathos and the seriousness of the situation, somehow conveys humor, the exact sort of humor, in fact, that we see in Ebenezer Scrooge’s journey through Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol.

Wry humor runs through the excellent catalog as well, as seen in the titles of three of curator Diane Wolfthal’s essays attest: “Your Money or Your Eternal Life?” “Will Money Damn Your Soul?” and “Can Money Save Your Soul?”

As modern, or perhaps as timeless as Bosch’s rendering of the risks of avarice feels, “Deathbed and Souls Tormented in Purgatory” from The Hours of Catherine of Cleves, circa 1440, is about as medieval as such images get. The “scene includes a woman offering the dying man a candle (a kind of ersatz last rite), a doctor examining his urine, a Carmelite monk reading a holy book and a woman praying. On the right, in the background, a fashionably garbed young man in blue and purple, presumably the heir, converses with an older, decadently dressed man who may be encouraging him to seize his inheritance. The heir, identifiable by his clothing, reappears in the lower margin raiding the dying man’s coffer; he reaches for a moneybag to add to the one he has already placed on the ground… The flames of purgatory on the facing folio await both the dying man and his immoral heir.” (87)

“Deathbed and Souls Tormented in Purgatory” in The Hours of Catherine of Cleves, illuminated by the Master of Catherine of Cleves, Utrecht, The Netherlands, circa 1440. The Morgan Library & Museum, New York City. Purchased on the Belle da Costa Greene Fund and through the generosity of the Fellows, 1963 and 1970. Janny Chiu photo.

Created near the end of what we term the medieval era, in both the Bosch and the illumination from The Hours, the images of avarice are limited to the desire for money and worldly goods. An image from around 1400, Andrea di Bartolo’s “Joachim and Anna Giving Food to the Poor and Offerings to the Temple” depicts prosperity properly transformed, not into more wealth, but into sustenance for the less fortunate and funds for the greater glory of God. In the painting, the gilding that surrounds the scene and adorns Joachim, Anna, the temple and the priests’ robes seems to signify the potentially smothering weight of wealth, a weight lifted in the holy act of giving. Instead of the transubstantiation of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, here we have bread and gold sustaining the collective body of humanity and the literal pillars of the church. More typical of the period are representations of the ultimate in New Testament avarice, Judas, and, conversely, the renunciation of worldly goods and earthly desires in the persona of St Francis, the Thirteenth Century mystic who would be canonized and found an order based in poverty. From Hungarian Anjou Legendary, “Judas Attempts to Return the Silver and Judas Hanged,” by the Hungarian Master and workshop, circa 1325-35, and the Master of St Augustine’s (?) “St Francis Renouncing His Worldly Goods,” painted circa 1500, embody this dichotomy in graphic detail.

In addition to the changing attitudes towards making money, the exhibition also dives deeply into the physical act of making money, that is, minting coins and constructing chests and buildings to store, protect and disseminate money. From the Morgan’s own holdings, Nicolò di Giacomo di Nascimbene’s “St Peter” and “Goldbeater,” a frontispiece from a register of creditors of a Bolognese lending society, circa 1394-1395, offers exceptional insight into the standardization of currency, a hands-on process involving the making of discs, or flans, of the proper weight and size (as seen here), the carving of dies, whose elements would be simplified throughout the medieval period, and the hammering of dies into the flans to create coinage. Not only were registers of creditors necessary, crucial to commerce were books that listed the fluctuating rates of exchange between the many currencies in use. A boxed balance with weights from Cologne, Germany, shows how those in the banking industry paid close attention to and kept track of these changes, while a medieval strongbox and an unearthed hoard demonstrate the lengths to which the wealthy would go to secure and protect their holdings.

Steel strongbox, possibly Nuremberg, Germany, late Sixteenth or early Seventeenth Century, 35¾ by 51 inches, 768 pounds. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, 1890. Gift of Henry G. Marquand.

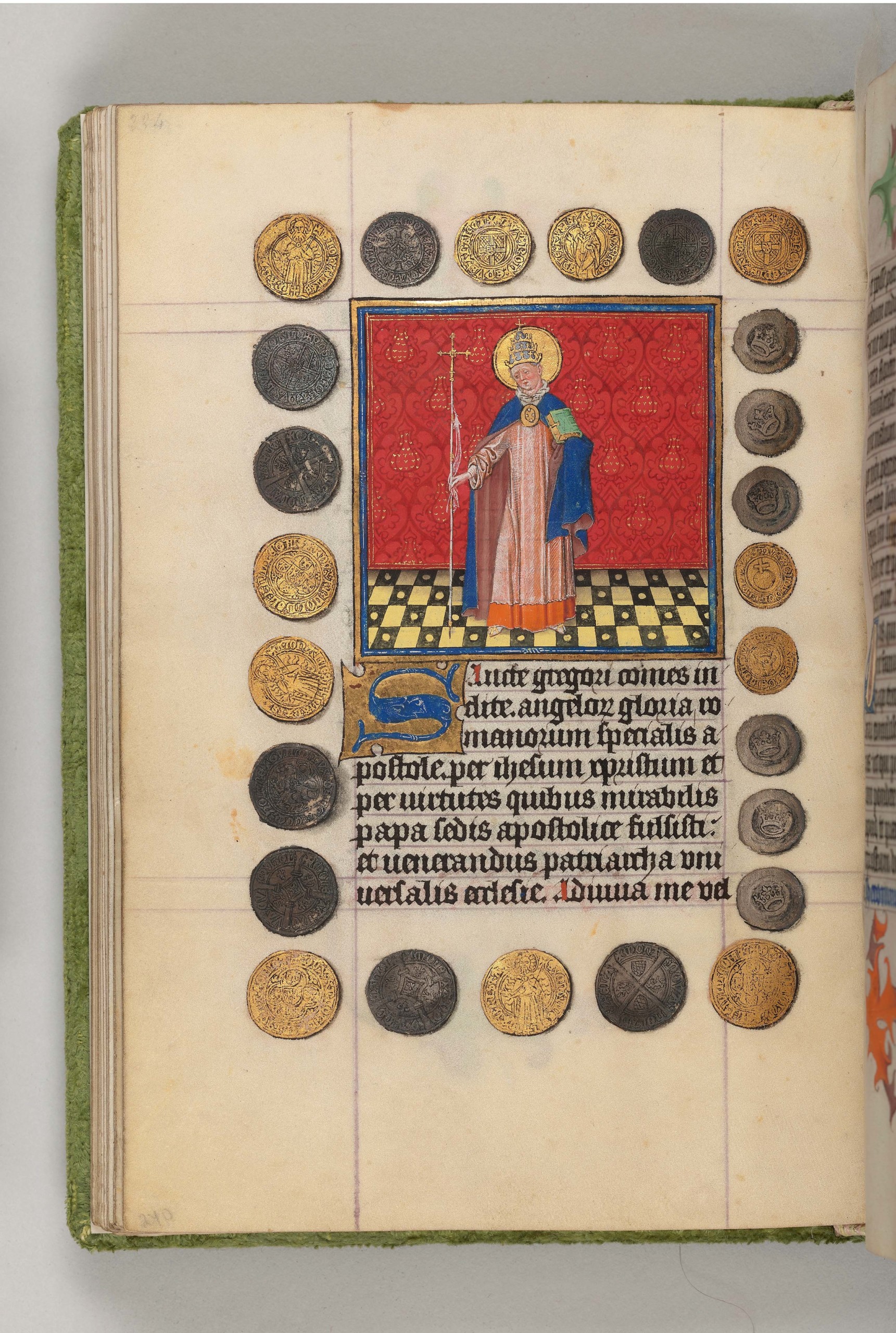

Eventually, the relative anonymity that merchants sought began to echo the authority that rulers derived from seeing their likenesses on coins, a practice that came from the examples of classical Greek and Roman coins as interest in antiquity intensified and principalities all over Europe struck exquisite artistic medals. At the same time, as new, post-plague mercantile economies gave rise to a new, moneyed class that sought respectability to accompany the acquisition of wealth and power, portraits of merchants begin to appear. The steady gaze from the subject of Jan Gossaert’s “Portrait of a Merchant,” circa 1530. “The merchant is alert and busy…shown writing, since literacy, unusual at the time, was a prerequisite for a successful career in commerce. Indeed, his thriving business is international in nature, to judge by the Hispano-Moresque dagger and the gold coin featuring Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. In short, this portrait visualizes the new mercantile ideal.” (cat. pp. 149-151) These kinds of clues, still life elements in portraits such as the dagger and coin, reveal, centuries later, the reach of the new mercantile, financial class. Uncovering and understanding them lies at the cutting edge of current art history, philosophy and practice. One work in the exhibition that eludes interpretation is yet another folio from The Hours of Catherine of Cleves. “St Gregory the Great and Coins” portrays the Sixth Century pope who was famous both for his insistence on helping the poor and his understanding that the Church needed a sound financial footing.

Despite this, it is difficult to understand why the illuminator surrounded Gregory with almost photo-realistic images of medieval coins (and why the illuminator altered a number of them). Objects such as this in the exhibition remind us that even though the people in “Medieval Money, Merchants, and Morality” were looking to solve problems similar to ours, there are significant differences between our rapid-fire, digital financial world and theirs. It is easier, in some ways, for us to find meaning in di Bartolo’s “Joachim and Anna” or “Deathbed and Souls Tormented in Purgatory” than in the coins that surround St Gregory. Those images belong to that period, that “then.” On the other hand, rapid changes in our own economy in which coins, whose use and meaning diminishes with every passing year as we pay and are paid, buy, sell and invest with the push of a key or button or swipe or tap of a card, let us know that our world is a blurry succession of “thens,” or “nexts” that we can barely envision. Half a millennium hence, what might an exhibition called “Twenty-First Century Money, Merchants, and Morality” at The (fill-in-the-blank with your favorite billionaire) Library & Museum look like? Pink Floyd once observed of money, “It’s a gas.” Five hundred years down the road, it might be more of a blast from the past.

“Medieval Money, Merchants, and Morality” is on view at the Morgan Library & Museum through March 10.

The Morgan Library & Museum is at 225 Madison Avenue. For information, 212-685-0008 or www.themorgan.org.