Tintoretto (1518/19–1594), “Holy family with the young St John,” circa 1549–50, oil on panel. Yale University Art Gallery, Maitland F. Griggs, B.A. 1896, Fund and Leonard C. Hanna Jr, Class of 1913, Fund.

NEW YORK CITY – The dramatic canvases of Jacopo Tintoretto (1518/1519-1594), with their muscular, expressive bodies, are some of the most distinctive of the Italian Renaissance. His drawings, however, have received less attention as a distinctive category in his oeuvre. Continuing at the Morgan Library & Museum through January 6, “Drawing in Tintoretto’s Venice” will be the first exhibition since 1956 to focus on the drawing practice of this major artist. It will offer a new perspective on Tintoretto’s evolution as a draftsman, his individuality as an artist, and his influence on a generation of painters in northern Italy.

Organized to mark the 500th anniversary of the artist’s birth, this exhibition brings together more than 70 drawings and a small group of related paintings. It places Tintoretto’s distinctive figure drawings alongside works by contemporaries such as Titian, Veronese and Bassano, as well as by artists – Domenico Tintoretto, Palma Giovane and others – working in Venice during the late Sixteenth Century, whose drawing style was influenced by Tintoretto’s. The exhibition also features a particularly engaging group of drawings that have recently been proposed as the work of the young El Greco during his time in Italy.

During Tintoretto’s lifetime, he was thought of as an impetuous genius, an artist who worked hastily, without careful design or consideration. Yet although Tintoretto was never an academic draftsman akin to his Florentine contemporaries, over the course of his career he forged his own distinctive style of drawing and his own way of using them. As his fame grew, his expanding workload required more assistants, and his drawing practice evolved. In training those assistants, he influenced a generation of artists in northern Italy. By the time of his death in May 1594, Tintoretto was the preeminent artist in Venice.

By 1537 or 1538, Tintoretto was an independent master. While many of Tintoretto’s drawings have been lost, from those that remain, we can trace his evolution from an early experimental mode of drawing akin to Schiavone’s, to an increasing attention on life study, and on to quicker, functional figure drawings intended to satisfy the practical needs of a busy painter.

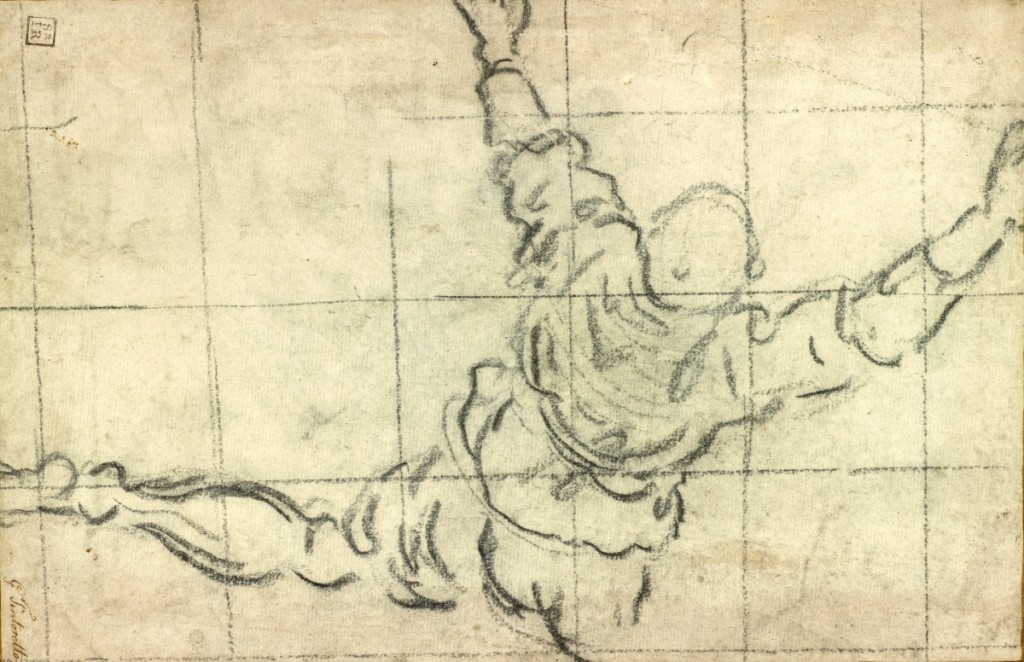

Tintoretto (1518/19–1594), “Study for a man climbing into a boat” (recto), 1578–79, charcoal, squared in charcoal. The Morgan Library & Museum. Gift of J.P. Morgan Jr. The Morgan Library & Museum, IV, 76. Graham S. Haber photo, 2012.

The watershed moment in Tintoretto’s career was the 1548 unveiling of his “Miracle of the Slave,” a work of a monumentality, drama and richness unseen in his painting to that point. The work led to subsequent commissions for the confraternity of San Rocco, the church of the Madonna dell’Orto, and, eventually to commissions at the Palazzo Ducale and the Scuola Grande di San Marco. His commission for the Scuola di San Rocco was a project that would occupy him on and off for the rest of his career.

The most familiar of Tintoretto’s drawings are the many studies after Michelangelo’s Samson and the Philistines and his sculptures in the Medici Chapel. A group of these studies is included in the exhibition, along with a cast of the Samson on which they are based. Although traditionally believed to be Tintoretto’s own youthful studies, the exhibition argues that these sculpture drawings are exercises that he used in his workshop to teach his assistants how to convey drama, meaning and sculptural presence of the human form.

In later years, Tintoretto’s workload increased to such a degree that his paintings were designed by him but executed by the workshop. His later figure drawings tend to be more simplified and abstracted than his earlier studies of live models, and they frequently adopt exaggerated musculature that was perhaps intended to emphasize form for the workshop assistants executing the paintings.

When the exhibition travels to the National Gallery of Art in March, it will be shown with “Tintoretto: Artist of Renaissance Venice,” a major retrospective focusing on his paintings.

The Morgan Library & Museum are at 225 Madison Avenue. For information, 212-685-0008 or www.themorgan.org.